Alicia Vikander: ‘It makes me sad to say, but women are very harsh against one another’

The Oscar winner talks to Patrick Smith about sexism on set, the battle for equal opportunities and speaking out against intrusive media coverage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When she was a young girl in Gothenburg, Alicia Vikander dreamt of a life in tutus. At 15, she moved to Stockholm and attended the Royal Swedish Ballet School, where she would dance seven hours a day, six days a week. Eventually, a chronic back injury put paid to her ambitions, but not before it had equipped her for Hollywood. “I’m very good with pain,” the Oscar-winning star of The Danish Girl explains. Moments later, she rolls up her trousers to reveal a recent scar on her knee. “Skiing,” she says in a stage whisper, gesturing towards her management team across the room. “But don’t tell them.”

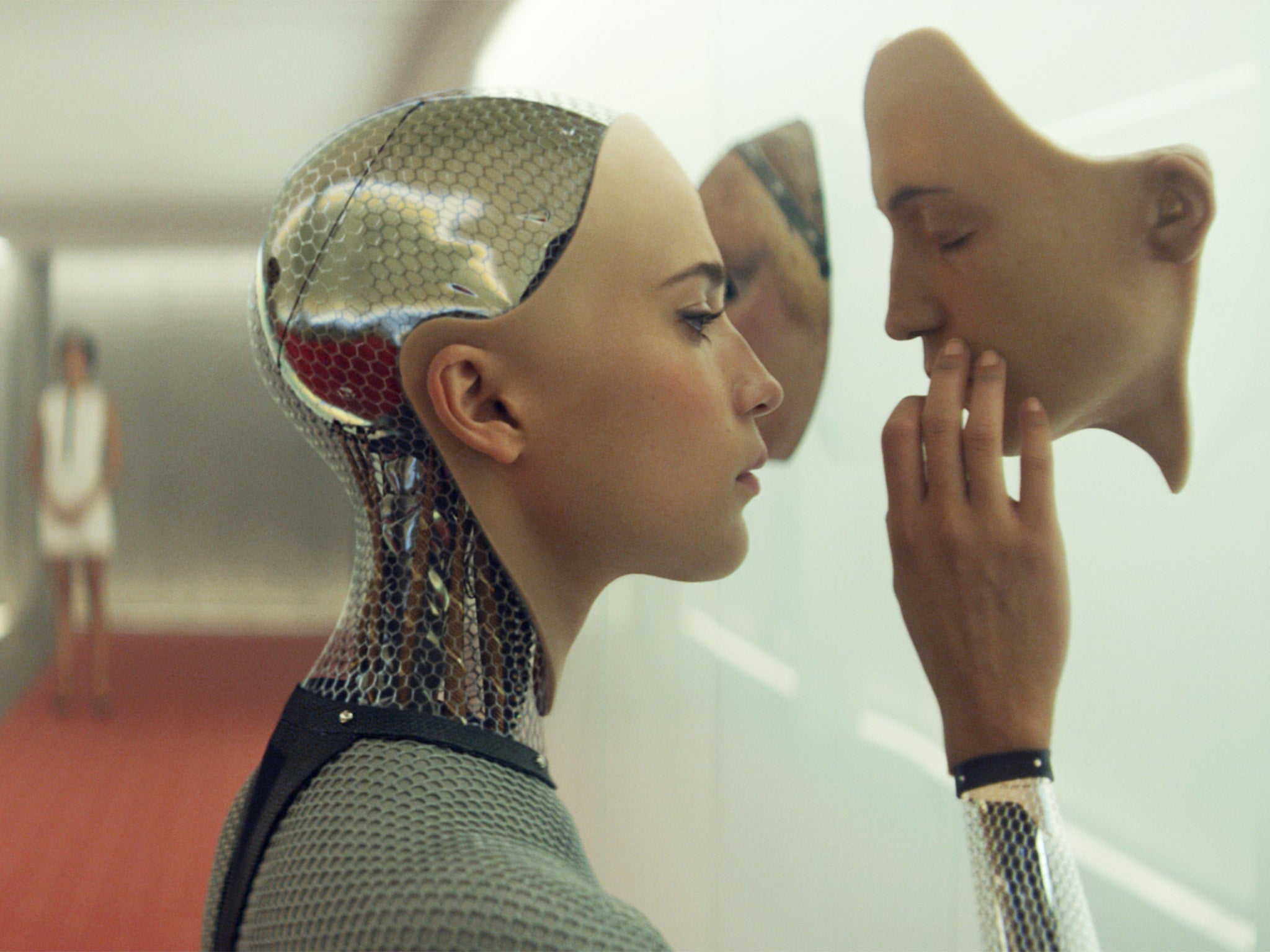

A high pain threshold helped the 31-year-old with the 2018 Tomb Raider reboot, for which she put on 12 pounds of muscle through weight training, rock climbing, swimming and MMA fighting. Her Lara Croft tempered being a badass with bruised vulnerability; her running, jumping and tumbling was defined (naturally) by a balletic grace. The dance training was there, too, in her laser-guided performance as a feminised android in Alex Garland’s sleek sci-fi thriller Ex Machina (2015). Adding a touch of artifice to the most natural movements – a raised eyebrow here, a tilt of the head there – she was at once bewitching and unnerving.

Vikander – who lives in Lisbon with Michael Fassbender, her husband and co-star in 2016’s The Light Between Oceans – meets me in a restaurant in central London. She’s wearing a double-breasted grey suit; a gold pendant shaped like a hand dangles from her neck. Emanating a breezy contentment, she has an indeterminate European accent suggesting no fixed abode. After passing up the chance to go to law school, she landed her first role in the 2010 film Pure, and within a couple of years, had appeared as the sheltered Kitty in Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina. Since then, she’s rarely returned to her homeland.

Today we are talking about her new Netflix film Earthquake Bird. Based on the book by Susanna Jones and directed by Wash Westmoreland (Still Alice, Colette), it’s a puzzle-box thriller about a deadly love triangle in 1989 Tokyo. It’s pulpy and slow-burning, with shades of the American noirs of the Seventies. And as Lucy Fly, a prim Swedish translator in Japan, Vikander is the best thing about it, her face a canvas of guilt, obsession and stoic defiance. Vikander, who learnt Japanese for the role in eight weeks, says the film is not “just murder mystery, but a mystery to get to know Lucy and figure out whether you can trust her”.

A review of the book, written by AN Wilson and published in The Daily Telegraph in 2002, called it “one of the best accounts of female sexuality, that subject of and mystery for any male reader”. “I think female sexuality is a mystery to anyone,” says Vikander when I quote the review back to her. Is it a problem, I wonder, that some male critics see female sexuality as a mystery to be solved? “It’s due to history that this male view has been allowed to build up. In this case, it sounds like it’s more [that critic’s] own fantasy that he puts on other women than actually talking about women’s own mystery. That’s probably why it sounds wrong.”

Vikander was mostly raised by her mother, actress Maria Fahl Vikander, after her parents’ separation. She has been one of many high-profile women in Hollywood pushing for change in an industry known for gender inequality and male entitlement. In 2017, she signed an open letter against sex abuse along with nearly 600 other Swedish actresses. Three years earlier, she had filmed one of the last movies produced by Harvey Weinstein, Tulip Fever, but has said nothing untoward happened, despite the fact that she’d “heard he was an incredible bully and that he does anything to get what he wants”.

When the Weinstein scandal broke, she recalled feeling “shock and disgust”. Yet before the #MeToo movement was triggered, Vikander starred in a film that now seems uncomfortably prescient. In Ex Machina, she played a robot servant to Oscar Isaac’s tech guru. The film was not only a reflection on humanity’s hubris, but also, I suggest, an allegorical tale about male ownership and objectification of the female body. She agrees, adding: “Sadly, this is what the world tends to do to women. For me, [my character] was a girl in a cage who needed breaking out. That’s how I saw it.”

Vikander’s own body came under scrutiny when she picked up the mantle from Angelina Jolie in the Tomb Raider franchise. One of the most egregious criticisms was that her breasts were not as pointy as Lara Croft’s in the original Nineties video game. Vikander admits it felt “invasive”. But, she adds, “the more and more people who mentioned it, the more I saw opportunities to speak out against it, and people seemed to be encouraging that at the end. It was an opportunity to show off a new kind of female role model.”

Vikander has experienced sexism on set, too. Indeed, in 2018, she revealed that Julianne Moore came to her defence after a man made a crude joke at her expense while they were shooting the 2014 fantasy Seventh Son. “I was really embarrassed, and I would have just laughed it off,” Vikander told Vogue, not naming the culprit. “But Julianne turned to him and said, ‘If you ever do that again, I’m walking out of here and I’m not coming back.’ She was just, like, ‘Don’t you f***ing say that again.’ It showed me that she had the power.”

Meeting Vikander, you get a sense she relishes speaking out about prejudice in Hollywood, although she rarely finishes a sentence before she’s vaulting off onto her next thought. As well as sexism and abuse, there is the age-old issue of actresses being pitted against each other. Does she think this has started to diminish?

“It makes me sad to say this, but women are very harsh against one another,” she says. “It’s all based on history and what we’ve been taught growing up and what is standard in society. I actually did a course in unconscious bias two weeks ago that was so interesting. Because women’s brains have been hard-wired to be like, ‘Oh, it’s a room, there must be like, two women here and 18 men.’ So, if I’m going to get my voice heard, I’m going to really have to speak up to get a chance. Over the last few years, the awareness that is being spread really changes the hard-wiring of your brain and you realise, ‘No, wait a minute, this is a bit strange.’”

The most noticeable change, she says, is that more women are being hired on film sets. I mention that intimacy coordinators are being brought in more regularly to ensure that actors never feel uneasy during sex scenes. “I’ve only just heard about that,” says Vikander. “I normally just do one take and I don’t bother doing two. It’s... the most uncomfortable thing for anyone to do. Nobody should ever be put in that situation where that is taken advantage of.”

Her naked scene with Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl, Tom Hooper’s fictionalised biopic of the transgender artist Lili Elbe, was tender and full of pathos. While images of it made the tabloids, it was the casting of Redmayne as one of the first people to undergo sex reassignment surgery that received the most column inches, with many representatives of the LGBT+ community arguing an actual transgender woman should have been given the role. I put this to Vikander. “It’s hard for me to talk about people in that situation, trans women and men,” she says. “But I do believe in being an actor. I want it to be that anyone can play anything. In movements like this, you need to make a stand and push for things to change. I think when trans men and women are playing cisgender and anyone can be up for any part, that’s where we want to get to.”

For Vikander, the way forward is to make sure equal opportunities are not simply a fad. “It’s getting the chance to get into the room and be up for a part because, as we know, not long ago women weren’t getting those chances,” she says with a smile. “Now, we’ve come this far, thankfully – that change is happening.”

Earthquake Bird is in cinemas now; it arrives on Netflix on 15 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments