Al Pacino interview: Hollywood's go-to gangster on why he has no regrets - not even Godfather III

'I have a life and do a lot of things, and so far my work has been my life. If I was a painter no one would question my age. I’m an artist, I hate saying that'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Al Pacino has so much chutzpah that he commands every room, every film set, and every theatre stage on or in which he appears. “I am a movie star,” he spouts at one moment, and he doesn’t want us to forget it. Even at 75, he has the brash confidence of youth, and yet his escapades of yesteryear provides the chorus to his oratory.

He makes jumps into the past with the voracity of Doctor Who. Speaking about the director of his new film Manglehorn, he says: “When David Gordon Green came to me with the script, I thought I would be interested in any movie working with such a good director.” And then he jumps of his own volition. “The first Godfather, Francis [Ford Coppola] wanted me and nobody else wanted me. The studios didn’t want me, nobody knew me, and I think when a director is interested I have a tendency to lean forward rather than backing off, even if I didn’t know what I would do in this part.”

The eponymous character he plays in Manglehorn is a man living in the past, who still writes letters to a woman he loved and lost many years ago. He is thrown into turmoil by Dawn, a bank cashier who takes an interest in his eccentric ways.

Talking about Manglehorn sees Pacino ramble about obsessions, the pertinence of Holly Hunter’s character being called Dawn, which then fuses into more praise for the director, before he ends on a commentary about his acting method: “I tried to make the performance come from the unconscious. When I look at it now, I guess that is what I did. I don’t work like that. I wish I talked to myself about that before.”

The danger with interviewing Pacino is that you let him run away with himself. He has been known to give 20-minute Shakespeare soliloquies in interviews. So it seems appropriate to ask him a more forthright question, in the hope that this works like a bucket of cold water.

Do you regret any of your movies? The Godfather: Part III for example? “What is that supposed to mean?” arrives his shortest response. So I repeat the question, omitting the Godfather example, and not mentioning much of the work he has done since the turn of the millennium. He stopped getting Oscar nominations in 1993 after he won his long overdue gong in 1993 for Scent of a Woman.

“I don’t regret anything,” he says with the bravado one would expect from one so brash. Then he checks himself. “I feel like I’ve made what I would call mistakes. I picked the wrong movie, or I didn’t pursue a character, but everything you do is part of you and you get something from it. Having the idea and excitement of being in these situation and places, they are more than just memories, they inform your life.”

He famously turned down the Han Solo role on Star Wars. Nonetheless, that’s probably a good thing, as it’s hard to imagine him as the loveable rogue. Yet there is one director he turned down whom Pacino seems to regret not having worked with. Manglehorn was filmed in Austin, the home of the reclusive director Terrence Malick. Pacino and his co-star Hunter would meet up with Malick in their breaks. “Terry, a long time ago, asked me to be in a movie, and I always wish, there is another one of my mistakes, there is a museum of mistakes, all the movies I rejected.” Pacino opted for Bobby Deerfield, one of Sydney Pollack’s minor works, rather than Badlands. He also turned down Kramer vs. Kramer, Pretty Woman and Die Hard.

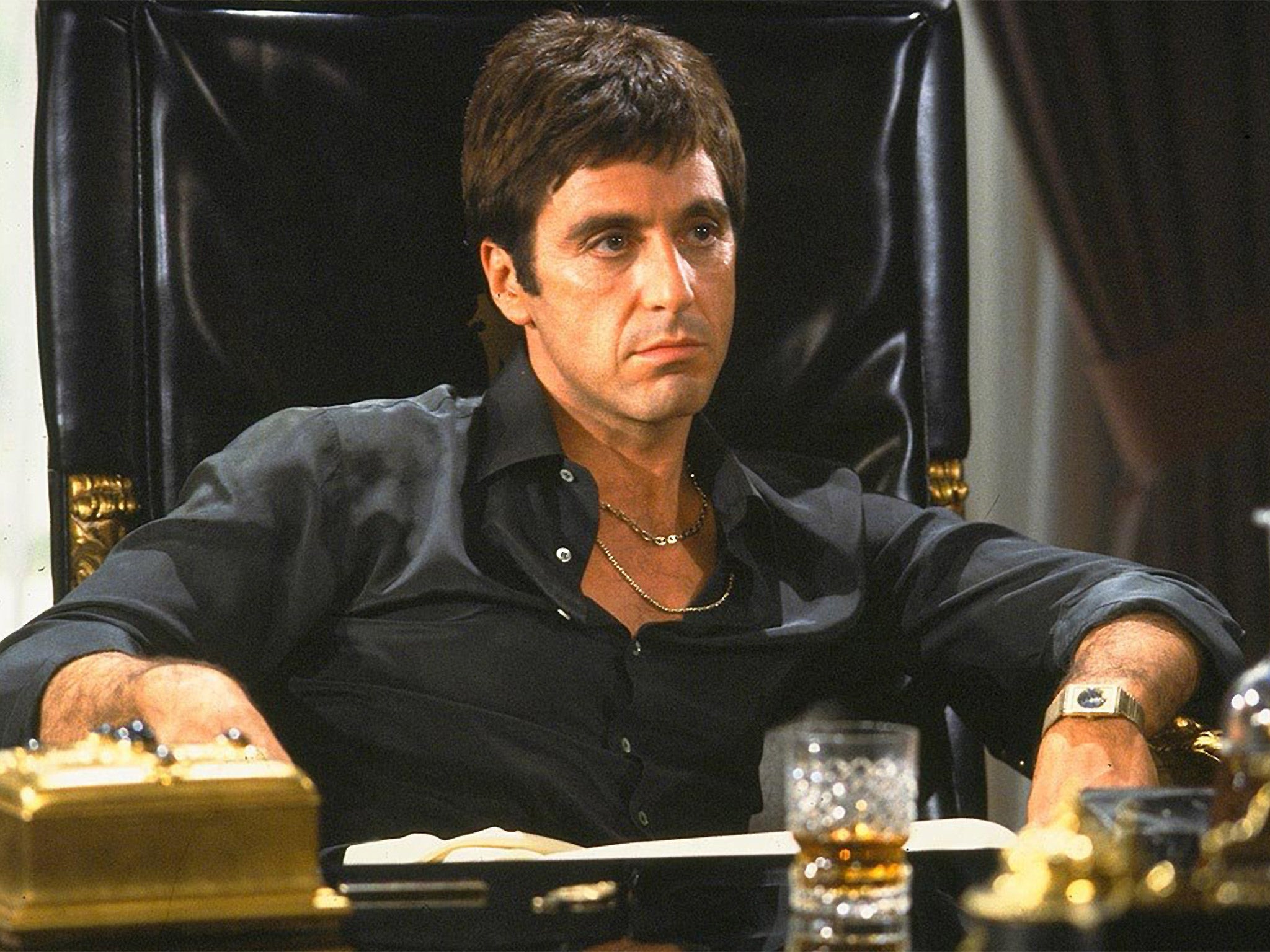

The greatness of his performances mean that sometimes the roles that he has played have taken on lives of their own. This has never been as true as with Scarface, in which he played the Cuban immigrant turned drug baron Tony Montana. The character and the life he lived have become a go-to for criminals, and lauded by a plethora of gangsta-rappers. The rags-to-riches story has been used to glorify violence. Does Pacino feel that his film has impacted culture in a negative way?

“Well I don’t know what to say about that, I don’t know.” But his moment without an opinion is short-lived.

“I look at Scarface and I don’t see that as the metaphor. I see what Brian De Palma was talking about when we made it. It was the crazy Eighties, the decade of avarice, greed and introducing that into the world; greed is good and the whole thing from Gecko in Wall Street. I thought it was a very socio-political statement, which is why rappers took to it. Hip-hop people were so buoyed up on Scarface. I know a lot of people who don’t deal drugs who are inspired by it. It’s about a kind of ingenuity, suddenly coming from the bottom and rising, which is why the original was so inspiring for me. There is something else too that seems to trigger off a certain thing, and that is this sense of his ideals as an outsider.”

Pacino was born in New York in 1940. His Italian-American parents divorced when he was two. He started smoking and drinking young and took menial jobs to fund his dream of becoming an actor. He took acting classes with Lee Strasberg. He started acting on stage in the late Sixties, and it was playing a heroin addict in The Panic in Needle Park that brought him to the attention of Coppola. The Seventies, he says, was a blur: the hit films, the fast life. He says he has never written a biography because he doesn’t remember much of the decade that saw him wow in Scarecrow, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and The Godfather.

“You don’t think of those parts as achievements,” he says of those heady days. “Imagine an actor saying, ‘I don’t want to go on anymore because I can’t outdo the last movie I made’. I might as well quit now. We call that resting on your laurels. You’re not supposed to do that. But I’m all for that, resting on your laurels, taking another profession, but for some reason I want to go back and do this stuff.”

He struggled to cope with the fame and adulation that came his way in the Seventies and he hit the bottle. His alcoholism began affecting his career, and he reached a point where he was out of work more than he was in work. “It’s a bit of a madness I get,” he says about the time before he changed his ways. “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke and I don’t do drugs.”

The Eighties saw his first career slump. He took a four-year break from making films after the epic failure that was Revolution, set just after the declaration of American independence, but continued to wow on stage. His love of Richard III and Salome has seen him make films revolving around the plays. He has never been married but has three children, the first with acting coach Jan Tarrant in 1989 and then twins with actress Beverly D’Angelo. He has been attached to a host of his co-stars, including a two-decade long on-off affair with Godfather co-star Diane Keaton.

In her autobiography, Then Again, Keaton says of Pacino: “He liked plain,” adding, “sometimes I swear Al must have been raised by wolves. There were normal things he had no acquaintance with, like the whole idea of enjoying a meal in the company of others. He is more at home, eating alone, standing up.” He has been dating 36-year-old Argentinian actress Lucila Sola since 2007, making light of their almost four-decade age gap.

In his heyday Pacino was commanding $14m a picture. In 2011 he was hit with a bill of $188,000 for failing to pay his tax in 2008 and 2009. His business manager at the time was Kenneth Starr, who was sentenced to seven years in jail for his part in a Ponzi scheme. Pacino promptly paid the bills and sent up his financial predicament when playing himself in the Adam Sandler comedy Jack and Jill. It’s his career nadir. It seemed a really long time since he made Heat, Donnie Brasco and Carlito’s Way in the mid-Nineties.

Recently Pacino seems to have a renewed zeal for making movies and choosing roles that suit his talents. In addition to Manglehorn, he has starred in Danny Collins, inspired by the true story of folk singer Steve Tiltson, and he optioned the 2009 novel The Humbling, about an aging actor suffering bouts of dementia. “I’m sorry for working so much,” he quips. “But I hadn’t worked for a few years. On HBO, on television I got good work, Phil Spector and Angels in America, they are portraits. If I find something and feel as though I can contribute to [it] in a way and feel I’m in it, whatever that means, I’m expressing something that I feel is a way to exercise my talent and help communicate a role as a human being in a movie, I will do that.

“You know I don’t talk politics and I don’t talk philosophy or anything like that, but if you look at my work, you might get an expression of me as a person. I think that is part of what we all do.”

As for the future, “I have things that are being developed”. One of which is his Manglehorn co-star Harmony Korine’s new film The Trap, and he hasn’t completed ruled out the long-gestating Martin Scorsese film The Irishman. It would put Pacino with one of the great directors he has never worked with, as well as Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci. One can only hope. “I’m actually, as they say, always trying to get out of show business. But I still think there is something for me to do, but it gets tougher.”

He doesn’t yet want to consider hanging up his gloves. “I’m not going to say the word ‘retirement’. Philip Roth, The Humbling is a movie of his book, he quit writing and he’s happy he says. He goes off and does what he does; I can understand that, so you look for other things. For me that is the director who wants to use you, the risks you take, the challenge, the fact you fall down, get up and go on. When you do it long enough, you want to go on. You want that challenge.”

His biggest challenge seems to be acting against his past. “We have to deal with our image, even though we play different characters, we have to deal with our image and that is part of why there is a kind of pretentiousness in saying that you are an artist, because you’re a movie star. That is wrong too, that is pretentious, to say ‘I’m a movie star’, so what do you say?”

He adds, “There are days when I do enjoy it. I have a life and do a lot of things, and so far my work has been my life. If I was a painter no one would question me about my age. I’m an artist, I hate saying that. One thing I learned early on, a woman I lived with said: ‘Whatever you do, don’t tell them that you are an artist.’ I said: ‘I don’t. I’ll avoid that.’ And I have been avoiding for many years to say that. Let’s put it this way, I think I’m an artist. I hope I am.”

‘Manglehorn’ is released on 7 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments