Agent provocateur: Slavoj Zizek takes on the 'ideology machine' of Tinseltown

Whether he's talking Stalinism, Catholicism or Kinder Surprise eggs, the ‘Elvis of cultural criticism is never far from controversy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The philosopher emerges into the back garden of a central London hotel, and he's already in full flow. He recently stayed in a very luxurious hotel, he says, but woke up in the middle of the night to find there was a rat in the room – he does an impression of a rat nibbling – and this was on the fourth floor. Which doesn't make sense, he says, because you'd normally see a rat in the basement, but one on the fourth floor inverts everything we believe about the hierarchical structure of cities…

Or words to that effect. I can't repeat verbatim what Slovenian thinker Slavoj Zizek said, because five minutes into the interview, I realise that my recorder hasn't been working. Normally, you might worry in this situation – what if you've lost the best quotes you'll get? – but in this case there's no need to fear; there's always plenty more. Zizek is an indefatigable talk machine: ideas, anecdotes, hearty expletives tumble out in a relentless flow over the 75 minutes of our interview, only sporadically prompted by a question from me. Or rather, the first few words of one, as that's usually all you can get out before Zizek shoots off on another tangent – veering from Titanic to 24 to the Israeli army to Maori art, with the odd obscene joke thrown in.

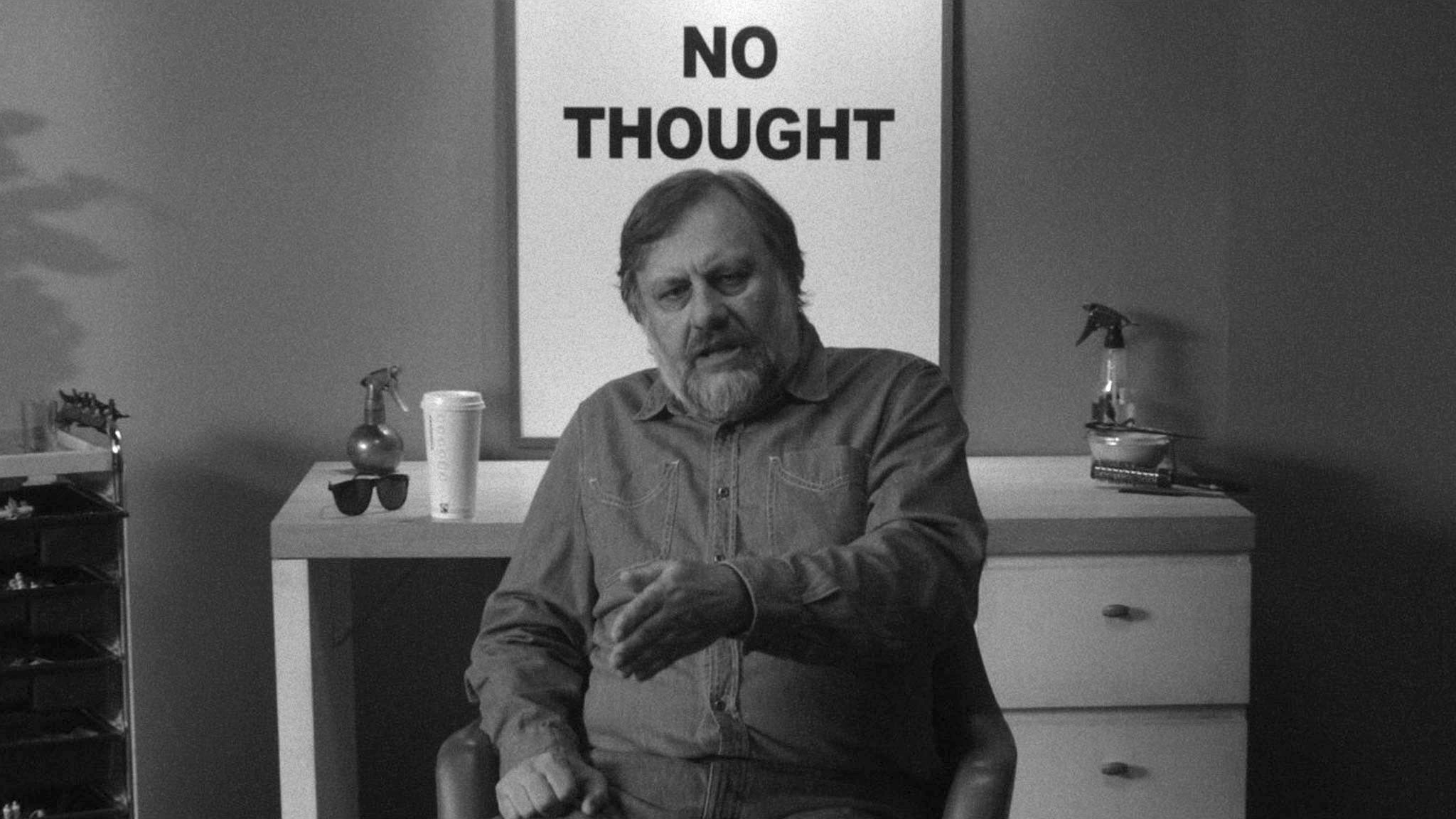

With a devoted following both within academia and in the wider media world, Zizek is the foremost intellectual heavyweight of our age – certainly the most fashionable. He is a theorist and commentator on, among other topics, ideology, current affairs, cinema and the thought of the notoriously abstruse French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. He has produced more than 70 books, including The Metastases of Enjoyment and the recent Less than Nothing, a monumental (1,056-page) cogitation on Hegel. As well as holding down an academic post in his native Ljubljana, he also teaches at such institutions as the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities in London, where he has just been holding a seminar entitled On the Notion of Event. "Which means whatever I want. It's a great trick to give titles which oblige you to nothing. I was totally unprepared; it went well."

Zizek's appearances on the international academic circuit, seemingly impromptu hyper-digressive tours de force, give free rein to an exuberant, bullish, often facetious persona that makes him considerably more approachable than the lofty theory icons of the 1970s and 1980s. If the likes of Jacques Derrida submitted philosophical concepts to gnomic scrutiny in something like the austere chill of an anechoic chamber, Zizek's ideas are more like protons ricocheting frenetically in the Large Hadron Collider of his brain.

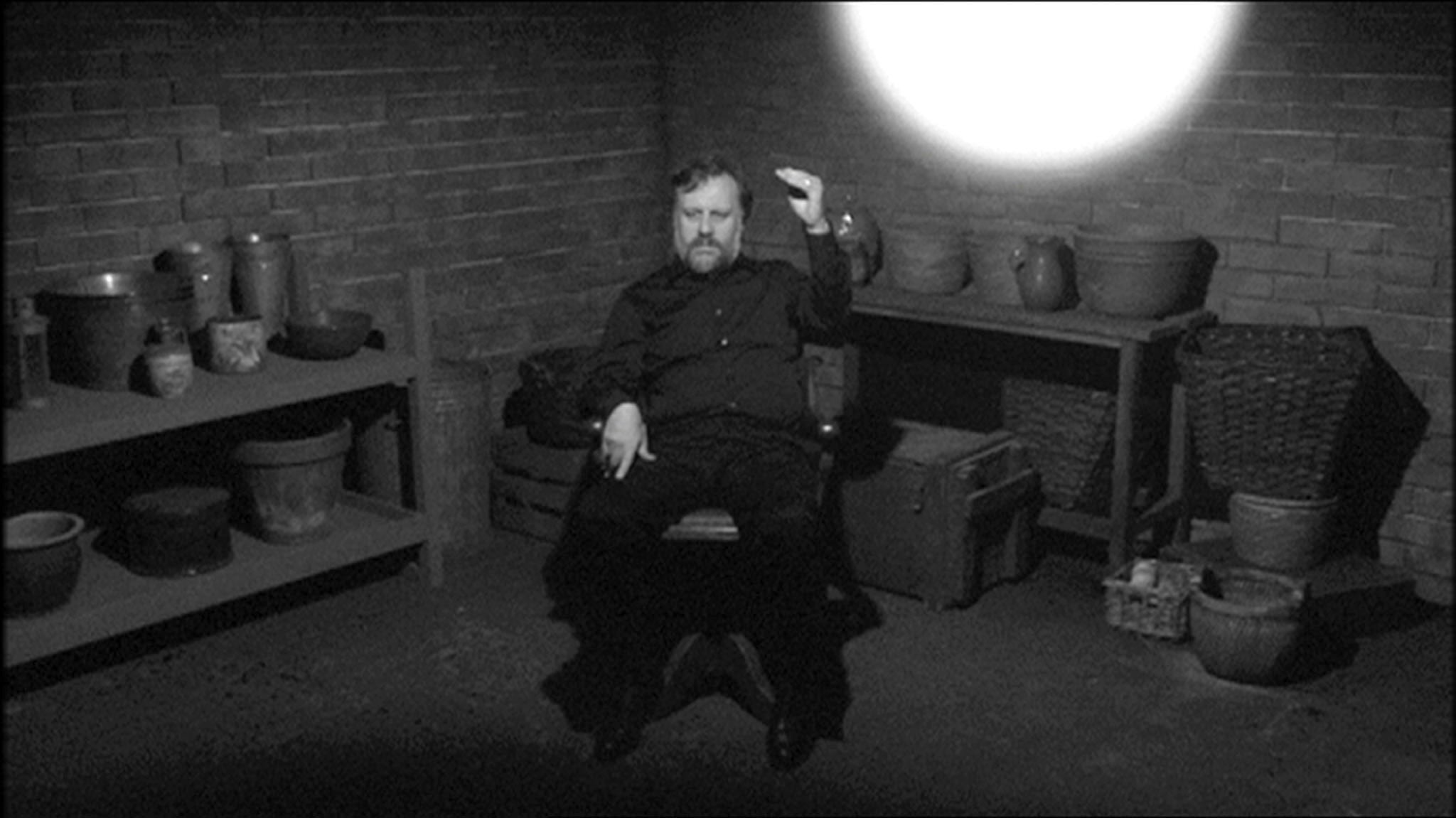

A hugely entertaining taster of Zizekian discourse is offered by a new film, The Pervert's Guide to Ideology. In it, Zizek riffs pugnaciously to camera on the meaning and effects of ideology, with reference to The Sound of Music, Brief Encounter, Beethoven's "Ode to Joy", Kinder Surprise chocolate eggs and the supposedly crypto-fascist stylings of German rock band Rammstein. The film is Zizek's second collaboration – following 2006's The Pervert's Guide to Cinema – with British director Sophie Fiennes, and it's far from a set of dry exegeses. It variously features Zizek sitting in a burnt-out plane in the Mojave desert; strapped to a hospital gurney, after Rock Hudson in 1966 thriller Seconds; and dressed as a priest to explain how the song "Climb Every Mountain" illustrates the ambivalent logic of Catholicism.

Zizek's critics are sceptical of his penchant for showmanship. But, he counters, even that most august German philosopher Heidegger was particular about his photoshoots. "He even made a very weird combination of part-leather, allegedly authentic local farmer's lederhosen, part-Nazi uniform. So there you have – my God! – the most radical guy questioning Western decadence, and he's fully caught in staging, no? I'm almost tempted to say that the more the philosopher is serious, the more he goes into this."

Zizek insists that he hasn't seen either of the films he's made with Fiennes – whom he jestingly calls "my Leni Riefenstahl" after Hitler's pet director. Zizek says he took her lead in making the film: she suggested topics and let him riff. "All I did – totally unprepared, that was beautiful – was I came to a studio, she said, 'OK, you put on this priest's frock, and remember what you said in that book about Catholicism and paedophilia, you improvise on that.'" When I talk to her later, Fiennes confirms that Zizek won't watch himself on screen. "That's a sign of his wisdom – if he did, he might get self-conscious. He knows he has all these tics and idiosyncrasies and it would be too inhibiting for him." She does, however, admit that Zizek's thoughts can be hard to follow. "You can't retain it as information – you have to engage with it almost like music, it's a very physical thing. Slavoj himself is very physical."

The physicality is part of Zizek's hugely entertaining personality, on screen and in the flesh. In conversation – although it's more a monologue – thoughts pour out at breakneck speed in near-perfect English (one of several languages he speaks), despite the odd dropped definite article. Large, shambling and shaggy in T-shirt and shapeless combat trousers, he punctuates his speech with frequent "my God!"s, the occasional "blah blah blah", and gleeful asides about what his "enemies" are bound to say about him – "Now again I will be accused of being a Stalinist!" As for tics, he has a habit of sniffing loudly, wiping his nose on the back of his hand, and he has a tendency to spray in his more sibilant utterances ("The implicit thesis is…"). When I pick up my iPhone, which is on the table through the interview, its surface is liberally flecked. It occurs to me that it might be worth putting on eBay – authentic philosopher's saliva or perhaps, to use Zizekian terminology, "the obscene excess of discourse".

Despite the gags with which he punctuates them, Zizek's written texts can be forbiddingly complex, and some critics complain that his habit of self-contradiction means that you can never be sure where he actually stands. That he's a provocateur is clear: an advocate of the return of Communism and a ferocious opponent of liberalism and capitalism, Zizek has a favourite trope, which is to claim that some notorious dictator or extremist wasn't radical or violent enough – be it Hitler, Stalin or the Khmer Rouge. One strand of his writing has offered a polemical defence of political violence, yet Zizek can also come across as an old-fashioned commonsense moral commentator. He recently attacked Kathryn Bigelow's film Zero Dark Thirty and her claim to be opening a debate on the use of torture; for Zizek, even to imagine making a case for torture was itself obscene.

"Let's be frank," he says, "I can imagine being in a totally desperate situation where, OK – I have a young son, I love him, some evil guy says, 'Ha ha! your son is being raped, tortured, I know where he is…' I can well imagine, out of pure despair, torturing this guy. But it shouldn't be rendered something normal, which you do reasonably. You should at least be aware that out of pure despair, you did something inadmissible. I'm becoming, my God, the old kind liberal at my age! I would like to live in a society where, when someone starts to reason these vulgarities, you don't even have to argue – you consider him as a jerk, an idiot, an eccentric bad-taste guy."

Zizek's star profile partly rests on his engagement with cinema – whether he's explicating psychoanalysis through Hitchcock movies, being interviewed by French cinephile journal Cahiers du Cinéma (and pausing to ask his interviewers whether they've ever met Emmanuelle Béart) or offering a critique of Avatar – then shamelessly confessing he hadn't even seen the film at the time. In A Pervert's Guide to Cinema, he declares that film "is the ultimate pervert art. It tells you how to desire" – a theme he expands on in the new follow-up.

Cinema, Zizek explains, "is an ideology machinery at its purest. If you want to grasp what is going on today in our societies, look at Hollywood blockbusters. Did Sophie include this one in the film – Kung Fu Panda? What I like is that on the one hand, it is all about this resuscitated Orientalist mythology – destiny, psychic powers – and at the same time, it mocks its own ideology with cynical remarks. Nonetheless, the ideology survives intact."

Zizek is especially fascinated with films that appear to say one thing, but actually – he contends – say the opposite. For example, "a film that I definitely dislike, Titanic. Blockbusters give you an official narrative which allows you, as a well-meaning left-liberal, to enjoy the film – but secretly satisfy your right-wing unconscious. Officially [Titanic is] ultra-leftist – but for me it's the story of a rich girl in a crisis who exploits a poor boy to suck the blood out of him to restore her ego."

Passionate about Hollywood, Zizek is unfashionably impatient with art cinema, although he'll make exceptions for Haneke, Kieslowski and sometimes Lars von Trier. "If a movie is poor, from some marginal group outside the studio system, it must be something authentic… No!" he booms, "sorry to tell you! I've seen these independent poor movies which are total boring shit! I will be very frank here – I recently saw it was on TV and beuggh!" – he emits a bellow of disgust – "I became a Goebbels, I mean, let's burn the movie, whatever. Namely, Cries & Whispers by Bergman – it's so pretentious!"

Today, in London, Zizek is planning to see Pacific Rim with his 13-year-old son, Tim. I ask him what he's learnt from his son – the younger of two – and he answers, videogames. He enthuses about a trip they both made to Korea, where gamers will play non-stop for two or three days at a time, feeding themselves intravenously and using catheters to avoid toilet trips. "I am not ready to dismiss this as some kind of bourgeois fetishist alienation – I like the fanatic ethics of it!"

As for musical tastes, Zizek admits to a long-time passion for Jefferson Airplane: "I'm the 1960s conservative." I have a nasty feeling, I tell him, that he might be an admirer of Frank Zappa – and he almost chokes in horror. "No! Hate him! Bluff! B-b-b-b-beuh! Frank Zappa – beurgh! But some of the early Jethro Tull – you're not so much into it? OK, here we politely disagree."

What Zizek really is, he says, is a Wagnerian. As a teenager in Ljubljana, before he got hooked on film theory, he dreamt of being an opera director. He still has aspirations in this area; earlier this year, the Royal Opera House announced a quartet of operas to be based on Zizek's texts, and his own dream project is a version of Antigone with three different endings. In the third version, neither Antigone nor her opponent King Creon wins: "The chorus steps in and says, 'These are your bourgeois feudal struggles,' and arrests them both."

As the interview ends, Zizek allows himself to be led to the back of the garden for a photo session. "Ah, I know this," he says, stepping in front of the photographer's screen. "You will project some naked prostitutes behind me. When I do a TV interview, they always make me sign a release, and it means, 'We can include your face into some hardcore movie and we're covered.'"

"I'm not going to do that," the photographer reassures him. Zizek seems offended. "Why not? Just don't say, 'Be natural, smile, laugh' – it's not natural for me. I always play this game, all my friends hate me for it – when someone laughs, I tell him, 'You are laughing, and children are starving in Somalia.' It's so cheap, this moralising! This is why I like the Bible…" And – from the Western misunderstanding of Buddhism, through the best filthy jokes told by Christian Palestinians, to what the Mayans would have said about "Gangnam Style" – philosophy's Mighty Mouth, without a pause for breath, is off again.

'The Pervert's Guide to Ideology' will be in selected cinemas from Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments