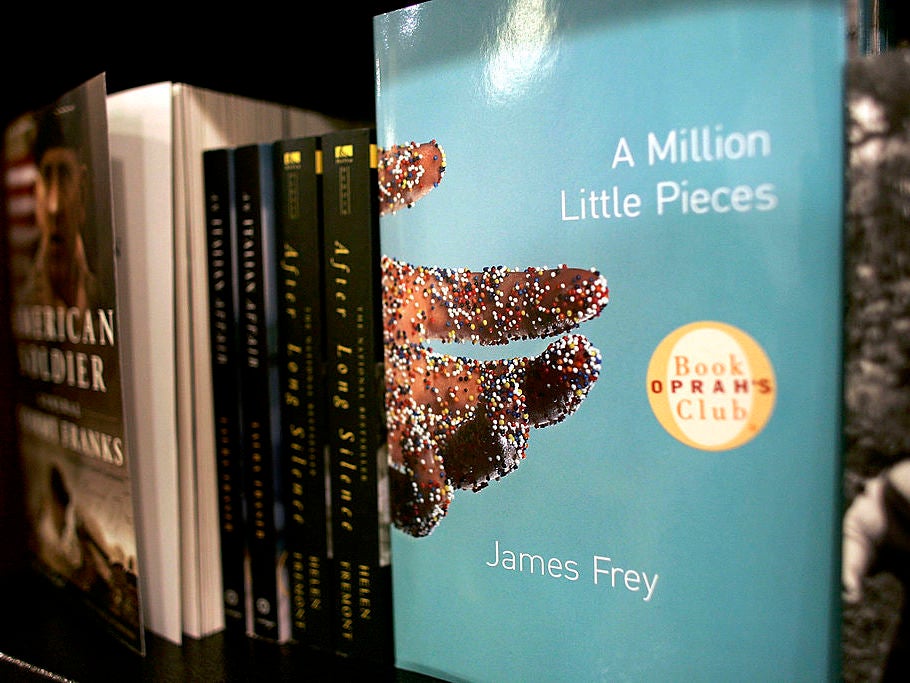

A Million Little Pieces: Without mention of its scandal, what is there left to say about James Frey’s addiction opus?

Sam Taylor-Johnson has brought the 2003 bestseller to the big screen while bypassing the controversy that trailed it, leading Adam White to ask: why bother?

James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces is a sprawling and manic novel about addiction, survival and redemption. It is also the least fascinating thing about A Million Little Pieces. The most captivating element of its existence is the noise that surrounds it – the accusations that it was largely faked, despite being marketed as a memoir, the literary-world war of words over its editing, and the piercing, terrifying glare of Oprah Winfrey, who elegantly destroyed Frey on live television over his apparent betrayal.

Thirteen years after that infamous Oprah interview, broadcast months after she had effusively praised Frey’s book and turned it into a phenomenon via her book blub, A Million Little Pieces has been adapted into a film. It is a well-made and well-acted drama, brought to the screen by artist and filmmaker Sam Taylor-Johnson and her actor husband Aaron, who plays Frey, but curiously excludes everything about the book’s post-publication journey. Outside of an opening quote from Mark Twain that reads “I’ve lived through some terrible things in my life, some of which actually happened”, nothing untoward is even hinted at. It is therefore a more traditional addiction/rehabilitation film, one that brings to mind an important question: without acknowledging the literary forgery accusations that engulfed it, what actually is A Million Little Pieces anymore?

Prior to its undoing, A Million Little Pieces existed as a brutally honest memoir about a man’s journey from rock bottom to salvation. Frey was 17, addicted to a potentially lethal combination of cocaine, meth and nitrous oxide, wanted in three states on possession charges and with a face turned inside out after falling head-first down a fire escape. By the time he arrived at a Minnesota rehabilitation centre, he had four missing teeth and a hole in his cheek. Rehab proved sordid, surreal and ultimately healing, a collection of equally damaged and addicted characters providing colour and guidance to the young Frey. At 23, he turned his experiences into a book, earning $50,000 from his publishers at Doubleday, an imprint of Random House.

In an aside that reads as unintentionally funny in hindsight, Entertainment Weekly wrote that “Frey doesn’t come across as a guy who says outrageous things to get attention”. A Million Little Pieces quickly emerged a hit, but it was elevated into the stratosphere by Winfrey, who endlessly promoted the book on her daytime talk show throughout the end of 2005 and helped it top The New York Times best seller list for 15 weeks in a row.

Frey additionally looked set to become a new kind of literary superstar, an obnoxiously overconfident and brash young writer with the acronym “FTBSITTTD” tattooed on his arm (standing for “F*** The Bulls***, It’s Time To Throw Down”) and little good to say about his contemporaries (“I don’t give a f*** what Jonathan Safran whatever-his-name does or what David Foster Wallace does,” Frey told the New York Observer in 2003). He was exhausting but undeniably exciting, a Charles Bukowski for the new millennium.

But there was also gloom on the horizon. In early 2006, the proto-TMZ site The Smoking Gun published evidence proving that a number of the book’s claims were untrue – Frey didn’t hit a police officer with his car and wasn’t sentenced to 87 days in jail as a result, but rather he spent five hours in custody after earning two misdemeanour traffic tickets. His alleged involvement in a train accident that killed two teenage girls was similarly untrue, as were many of the relationships he claimed to have developed in rehab.

Both Frey and Winfrey initially shrugged off the allegations, Winfrey calling into Larry King’s talk show to defend her new favourite memoirist. “The underlying message of redemption in James Frey’s memoir still resonates with me, and I know it resonates with millions of people who have read this book,” she said. “To me, it seems to be much ado about nothing.”

Two weeks later, however, Winfrey’s perspective had changed. Rather than continue to defend Frey, she decided to confront him in a televised special. Frey and his publisher Nan Talese have claimed that Winfrey and her producers had invited the pair onto the show under the pretence of talking about “truth in America”, but they ended up walking into an ambush. Winfrey has always insisted that she was open about her intentions.

In front of a packed studio audience, Winfrey told Frey that he had “betrayed millions of readers” and that she felt “duped” by the claims in his book. Frey confessed that many of the claims made by The Smoking Gun were true, and that he had falsified a number of experiences recounted in his book. “I think one of the coping mechanisms I developed was sort of this image of myself that was greater than what I actually was,” Frey said, by way of explanation. “In order to get through the experience of the addiction, I thought of myself as being tougher than I was and badder than I was and it helped me cope. When I was writing the book, instead of being as introspective as I should have been, I clung to that image.”

Despite Frey’s apparent sincerity, Winfrey persevered in her line of questioning. “I acted in defence of you and as I said, my judgment was clouded because so many people seemed to have gotten so much out of it,” she told him. “But now I feel that you conned us all ... I think you presented a false person.”

In the wake of Winfrey’s confrontation, literary figures distanced themselves from Frey. He was dropped by his publisher and agent, and Warner Bros abandoned the film adaptation they had been prepping (Gus Van Sant was in negotiations to direct). But questions still remained about how much Frey was encouraged to embellish his own narrative, and whether Random House knew all along that Frey’s “memoir” was more fiction than fact.

A Vanity Fair feature additionally alleged that Frey had been directed to exaggerate his story by one of his editors at Doubleday, and that Frey had expressed unease with the marketing of A Million Little Pieces as a memoir long before it had actually been published. “I think of this book more as a work of art or literature than I do a work of memoir or autobiography,” Frey wrote in an “author’s questionnaire” used for marketing and publicity purposes in advance of publication. By the time all of this was unearthed, however, it had ceased to matter. Frey had already become persona non grata, hounded by photographers, jeered at by the public and scorned by Winfrey.

It was a scandal that, like the recent reappraisal of the rise and racism-assisted fall of Jade Goody, works as an unexpected time capsule of what constituted a pop culture crisis in the years immediately preceding Twitter. Just as Goody’s racism towards Shilpa Shetty – in an era of Blairite delusion that the UK’s problems with classism and racism were a thing of the past – appeared like something truly shocking, we couldn’t quite believe that such a popular public figure had presented an untruth in the way Frey had. And to Oprah Winfrey no less. This was an era, after all, in which truth was considered sacred, and the idea of a figure not being entirely truthful about something warranted public flogging. Looked at today, such a horrified and angry reaction to a lie seems almost quaint.

“Some people think memoirs should be held to a perfect journalistic standard,” Frey told The Guardian in 2006. “Some people don’t. Obviously I don’t. My goal was never to create or to write a perfect journalistic standard of my life. It was always to be as literature. I thought in doing that it was OK to take certain licences. To tell a story effectively you manipulate information ... I think that if stories were told always exactly as they really happened most of them would be really boring.”

Frey did recover somewhat, working on increasingly poorly-reviewed follow-up books (all fiction, it should be noted), and setting up his own young-adult publishing company that was accused by New York Magazine in 2010 of taking advantage of aspiring student writers. And A Million Little Pieces continued to sell, only with an apologetic author’s note tacked onto the front and book stores recategorising it as fiction. Winfrey, too, came around, revealing in 2011 that, after years of meditation, she felt she had initially been too hard on Frey in 2006 and sought his forgiveness. But Frey’s continued survival has also bred a number of questions in itself – are we still too forgiving of wealthy white men when they happen to be great artists? And does the undeniable power of A Million Little Pieces override the fact that elements of it never actually happened?

There’s still much to admire about A Million Little Pieces, in its stream-of-consciousness energy and drug-fuelled gnarliness, while the questions it provokes today about fact and fiction and Frey’s downfall almost enhance its power. So much, in fact, that on film it feels like something is missing. That Taylor-Johnson chose to dramatise the version of James Frey that more-or-less existed years before he became a literary villain isn’t a travesty, but it feels like a missed opportunity. Because the post-scandal Frey is compelling in a slightly more interesting way than the addict described on the page, a man who is simply frustrating and vaguely reprehensible. Taylor-Johnson’s A Million Little Pieces is solid and moving and depicts addiction at its most raw and unflinching, but it also cuts to the credits just when things get interesting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks