Die Hard at 30: How the every-dude action movie defied expectations and turned Bruce Willis into a star

Despite gambling on a cast of relative unknowns, Die Hard used wit, style and dangerous stunts to become – as Ed Power explains – one of the greatest action movies ever made

On 2 November 1987, Bruce Willis, having just dashed from the set of hit TV romcom Moonlighting, found himself gazing down from the roof of a five-storey parking garage on the Westside of Los Angeles.

It was his first night shooting his new movie. He was about to make a literal leap into the unknown, jumping into the crisp LA night as a ripple of explosions lit up the dark behind him.

The film, of course, was Die Hard. John McTiernan’s valentine to every-dude grit, pump-action one-liners and blood-stained vests would achieve more or less immediate recognition as one of the greatest action movies ever made. When it had its inaugural British screening at London Film Festival a little over a year later, on 27 November 1988, it reduced a room of cineastes to “oohs” and “aahs” of suspense, and whoops of excitement.

On the 30th anniversary of its UK premiere, Die Hard’s genius is indisputable. Its innovation was to take a straightforward premise – criminals hijack a skyscraper (the still under construction Fox Plaza standing in for fictional Nakatomi tower) only for a lone-wolf cop to take them down one by one – and commit to it entirely.

Along the way, Die Hard gave us one of the all-time great cinematic villains in Alan Rickman’s German terrorist Hans Gruber – the alpha and omega of the Hollywood Euro-baddie. And there was a readily identifiable hero in Willis’s stubbled-and-fed-up John McClane.

There were aspects of the classic buddy movie to Die Hard – Reginald VelJohnson brought rollicking energy as McClane’s man on the outside, Sergeant Al Powell – but it functioned as a family drama, too. The only reason McClane was in Nakatomi Plaza, after all, was to reconcile with wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia, aunt of Macaulay Culkin) who had jeopardised their marriage for her soaraway corporate career (the only aspect of the plot to feel horribly dated).

Amid the mayhem were lashings of dark humour. Gallows wit was a sensibility Willis had picked up on during his research for the part, when he spoke to cops who had found themselves in real-life hostage situations.

“This could easily become a very heavy, kill everybody film,” Willis said. “[But] when your life is on the line, you could die any moment, a very strange sense of humour comes out. From the research I did, talking to the various officers... they helped me to find that black humour.”

Die Hard was an enormous success, earning $141m on a $28m budget and sending reviewers swooning (one exception was doyen of movie criticism Roger Ebert, who dismissed it as a “mess … which shoots itself in the foot”). It raised up Willis from everyday stardom to global celebrity and imbued overnight fame on Rickman, then an obscure stage actor. It furthermore sparked an eternal debate as to whether this Christmas Eve-set blockbuster is, or isn’t, a Yuletide movie. Willis thinks not; the internet remains bitterly divided.

But all this lay in the future as Willis, having hastened straight from MGM Studios at Culver City, reported for his first day of work. Utmost in his mind was the literal leap into the unknown he was about to take.

“I’m up there on the roof,” Willis would later tell Entertainment Weekly, “they’re strapping the firehose around my waist and they’re slathering me up with this stuff and I said, ‘What’s this for?’ And they said, ‘That’s so you don’t catch on fire. See those big plastic bags of gasoline over there? We’re gonna blow them up when you jump!”

Up to this point in his professional life, the hairiest endeavour undertaken by Willis had been exchanging zinging one-liners with Cybill Shepherd on Moonlighting. The series was a spicy update of the Tracy/Hepburn school of “will they/won’t they?” romantic comedy. Now here he was, strapped to a firehose, surrounded by jury-rigged incendiaries.

“When I jumped, the force of the explosion blew me out to the very edge of the air bag I was supposed to land on,” he recalled.

“And when I landed everyone came running over to me, and I thought they were going to say, ‘Great job! Attaboy!’ And what they were doing is seeing if I’m alive because I almost missed the bag. Finally, I was like, ‘Why would you shoot this scene first?’ And they were like, ‘If you were killed at the end of the movie, it would cost us a lot more money to reshoot the whole thing with another actor.”

Die Hard is one of cinema’s outstanding rollercoaster rides. It was also among the most influential movies of the Eighties. The formula of “lone everyman up against stylishly attired baddies in spatially confined environment” was to prove endlessly malleable. McClane’s night at Nakatomi Plaza would inspire Speed (Die Hard on a bus), Passenger 57 (Die Hard on a plane), Under Siege (Die Hard on a battleship), Cliffhanger (Die Hard on a mountain), Con Air (Die Hard on a prison plane)... the list goes on. Much later, Willis recalled being pitched an action movie described as “Die Hard in a skyscraper”. “I think they already did that,” was his answer.

But on the first night, up there on that roof, such success would have struck those involved as fantastical. Willis simply wanted to make it out alive. Everyone else wanted to make it out with their reputation intact.

The script, by veteran Steven de Souza (Commando, 48 Hrs) and newcomer Jeb Stuart, was still very much a work in progress, with many of Die Hard’s most memorable scenes cobbled together on the fly. Consider the sequence in which Gruber runs into McClane and pretends to be a hostage. It came about after De Souza overheard Rickman trying out his American accent on the crew. Several hours later, he’d bashed out a page of dialogue and cameras were rolling.

One glimmer amid the chaos was the one-liner Stuart and De Souza had already cooked up for McClane (though Gruber would arguably get the best piece of dialogue in “Mr Takagi ... won’t be joining us for the rest of his life”). The McClane catchphrase was inspired by old cowboy lingo. The idea was that it should underscore McClane’s all-American strut.

The difficulty was that nobody was quite sure how to deliver it correctly. “We had a really adult conversation about what was the proper way to say it,” Willis remembered. “Was it ‘Yippee-ki-yay, mother****er’ or ‘Yippee-ti-yay, mother****er’? I’m glad that I held on to ‘Yippee-ki-yay.’”

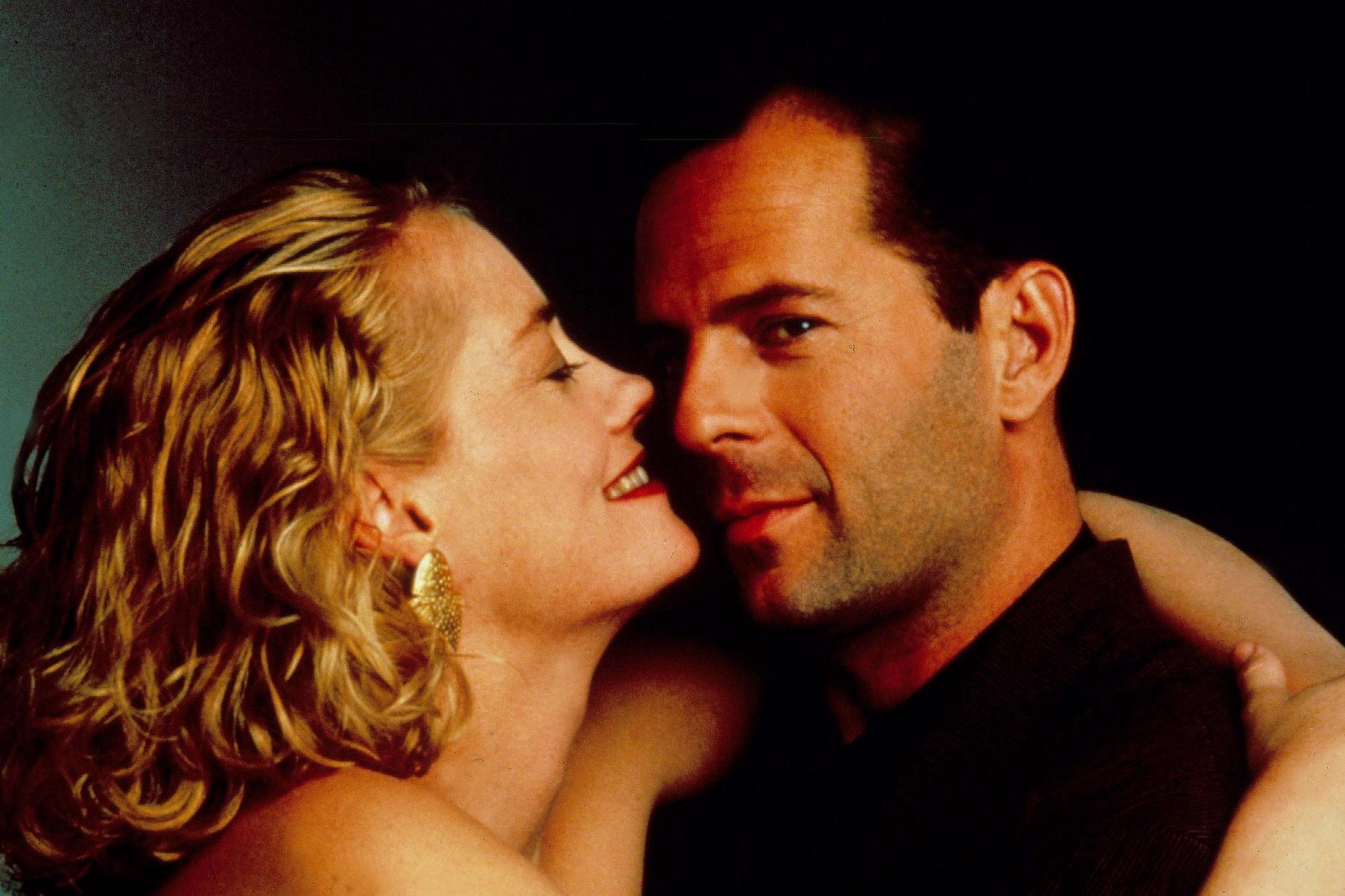

Willis was, in 1987, an unknown property outside comedy. He’d had a hit opposite Kim Basinger in that summer’s Blind Date, a romcom posited on the innate hilarity of Basinger as an out-of-control drunk. Die Hard was something else entirely – and conventional wisdom in the late Eighties held that for an action movie to punch through, it had to star a bulging strongman who acted with his pecs.

It was exactly this formula that had given director McTiernan his breakout smash with Predator. But where that film had featured an established action A-lister in Arnold Schwarzenegger, the stars of his new project were either unknown (Rickman) or regarded as the very opposite of a muscled hero (Willis).

Willis had, in fact, been at the bottom of the wish list for producers Lawrence Gordon and Joel Silver (48 Hrs, Lethal Weapon). For complicated contractual reasons, they’d been obliged to offer the part of John McLane to Frank Sinatra, then in his seventies. Rather improbably, in 1968 Sinatra had headed the cast in a loose prequel to Die Hard, The Detective (both films adapted from thrillers by Roderick Thorp) and had first dibs on the follow-up.

When he sensibly declined, Schwarzenegger was approached. Ironically, as Willis was trying to escape from comedy, Schwarzenegger was attempting to break into the genre by starring alongside Danny DeVito in Twins – also released in 1988 – and so turned Die Hard down.

With Schwarzenegger out, Gordon and Silver cast their net a little wider. Richard Gere, Burt Reynolds, Harrison Ford, Sylvester Stallone, Nick Nolte, Don Johnson, Mel Gibson, even MacGyver himself Richard Dean Anderson were all sounded out. Each said no. As did Willis initially – for reasons that had less to do with Die Hard than with his contractual obligations to Moonlighting.

But then he had a stroke of luck: his co-star Cybill Shepherd was pregnant, requiring Moonlight to shut down for nearly three months. “I’d already read the script for Die Hard once, but had to pass because of the show,” he said. “As it turns out, a miracle happened – Cybill Shepherd got pregnant and they shut down the show for 11 weeks – just the right amount of time for me to run around over at Nakatomi tower.”

Willis insisted on largely doing his own stunts on Die Hard – tumbling down stairs, jumping off rooftops and so forth. McClane’s blood and sweat-stained vest would duly become part of Hollywood iconography – a metaphor for how Die Hard had set itself apart from the Eighties school of action flicks, with their invincible heroes and hammy dialogue.

Die Hard’s true authenticity, however, sprang from Willis’s identification with the character of McClane. In Moonlighting, he’d played a charming gadabout – a lifetime removed from his blue collar upbringing in New Jersey. McClane was closer to who he felt he really was – an average guy just trying to get through the day.

Willis’s take on Die Hard’s hero was that, had someone else offered to step in and fight the bad guys, McClane would gladly have handed over his blood-stained undershirt. He was a white knight by default, not choice.

“The thing about the first film you have to understand is I was doing TV,” said Willis. “I’d only been in LA for a couple of years, I was still really learning how to act, so most of what went into making John McClane from a character standpoint was the South Jersey Bruce Willis – that attitude and disrespect for authority, that gallows sense of humour, the reluctant hero.”

The realism was further heightened by the choice of the still under construction Fox Plaza as stand in for Nakatomi tower. Because 20th Century Fox had a stake in the unfinished building, McTiernan was able to use several floors as his own private playground. The early scene where McClane dukes it out with Gruber’s goons was, for instance, filmed in an actual construction site – providing a grittiness that action movies of the period typically lacked.

As Die Hard would make thumpingly clear, McTiernan was one of those rare directors with an instinctive feel for action. “With John McTiernan and Spielberg and some other directors, you know exactly where everybody is, so when chaos breaks out, you know which end is up,” Die Hard cinematographer Jan de Bont (later to direct Speed) told Slash Film. “Is this hero in danger? Are the villains getting close? John McTiernan and I, and the stunt team, walked throughout the entire building. So we had reality printed on our minds.”

The other factor in Die Hard’s success of course was Alan Rickman – who established the archetype of the Hollywood Euro-villain with the magnificently amoral Hans Gruber. Rickman had been cast in the part after producer Silver saw him waxing nefariously as Vicomte de Valmont in the Broadway run of Les Liaisons Dangereuses.

In his early forties, Rickman was perfectly happy as a well-regarded, thoroughly obscure stage actor. What Die Hard represented was a paycheque and an opportunity to dip a toe in cinema. He had little inkling as to where it would lead.

“Die Hard was a huge event in my life,” Rickman told me in 2015, less than a year before his death from pancreatic cancer at the age of 69. “I walked into a screening in New York anonymous and walked out not anonymous. You are aware that something has happened. It was the first film I ever made – I was very ignorant. Nowadays, everyone wants to be in an action or superhero movie, I notice. Then, it was very weird for me to do it.

“What seems to have been forgotten along the way,” he concluded, “is that Die Hard has wit and style. That’s why it lasted.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks