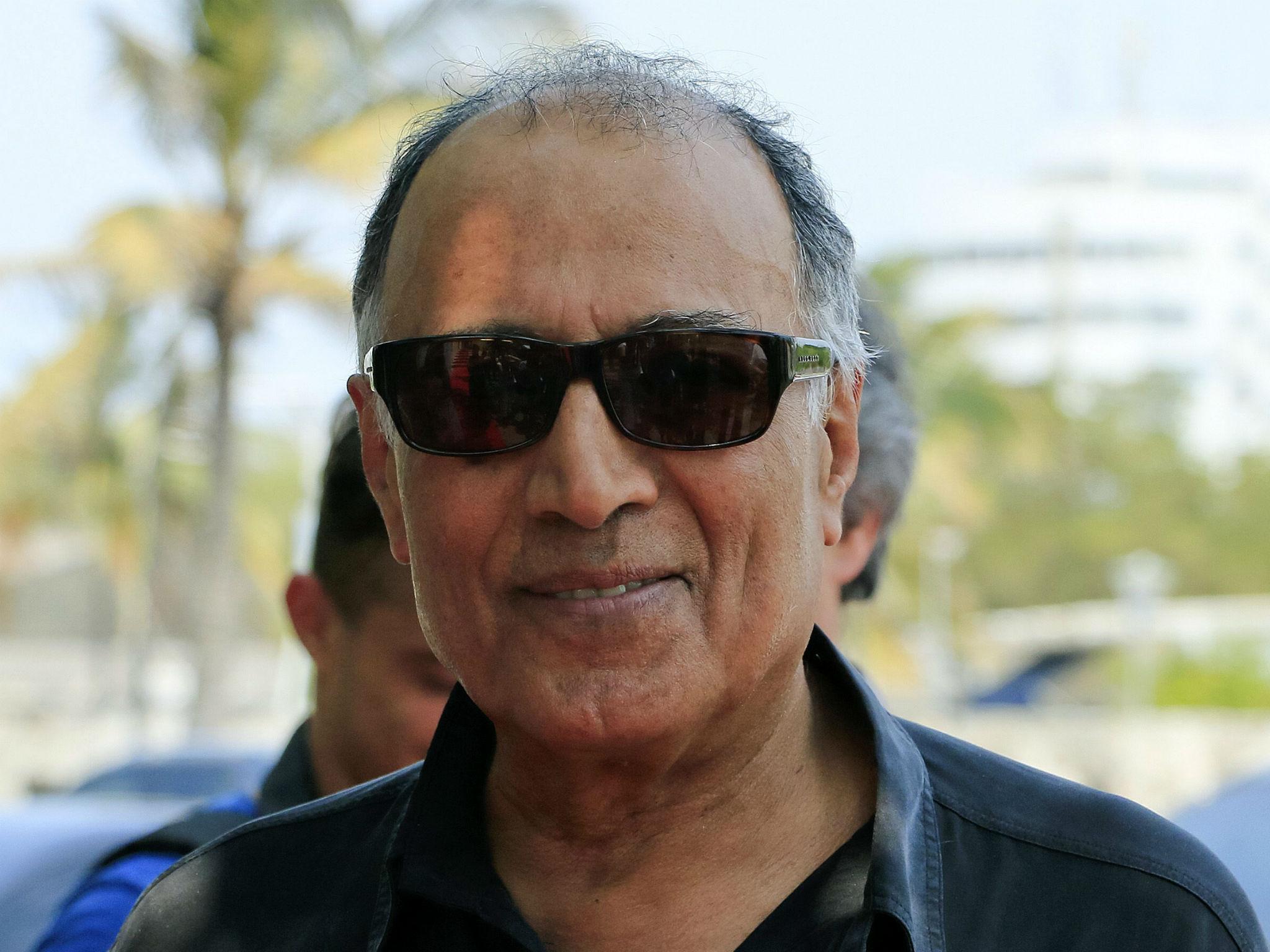

Abbas Kiarostami: A filmmaker who offered audiences, especially those in the West, a window into life in Iran

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As a poet, photographer and, most famously, filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami always seemed to have an incredible knack of creating the maximum impact with minimal resources. At first glance, his stories seem simple, but that was a veil he used to mask the complex and complicated questions he posed about Iranian society.

Kiarostami offered audiences, especially those in the West, a window into life in Iran, when for the most part the media and governments were bombarding us with stories about madcap Ayatollahs and fatwas. The films were imbued with criticism of the governments, but were crafted to also allow him to work within the confines of Iranian censorship. The director never went into exile, unlike many of his filmmaking contemporaries, yet this did not stop him from posing the tough questions.

It’s rare that a director gets to start his own film wave, where a group of contemporaries follow an artist’s lead, continuing to make work in his style and form. For a time in the 1980s and ’90s, the Iranian New Wave was the envy of the world, and Kiarostami the first among equals.

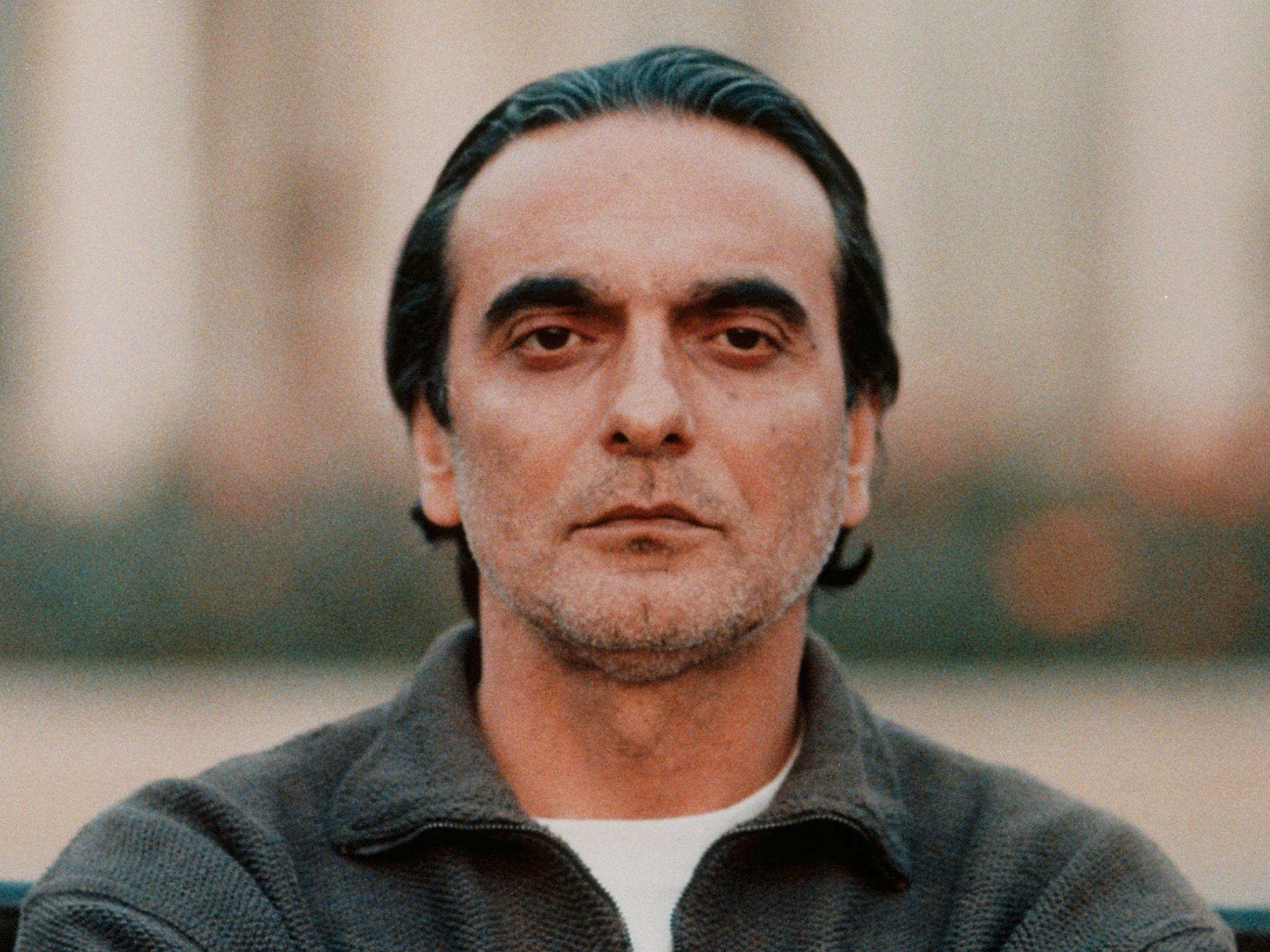

He won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1997 for Taste of Cherry. The film is quintessential Kiarostami. It tells the story of fiftysomething Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) who is on the verge of suicide, an act that is seen as a sin in Islam. Badii drives around, picking up passengers, hoping to find someone willing to take the ‘job’ of burying him. Just by mentioning suicide, Kiarostami ensures that the people Badii tries to convince are not just facing a personal dilemma, but would need to go against the state. It is a reminder of the political situation that they have to live with. This is feat that Kiarostami manages in nearly all his films, to bring out a complexity in the seemingly simple.

Most of the action in Taste of Cherry takes place inside a car, a vehicle used by Kiarostami in many films in order to create a private sphere in a public space. The confined private setting allows the inhabitants to be more forthright than if they were out in public, so creating a discussion that is honest and real.

It‘s this element of truth that has often led to the Iranian director being talked of as a neo-realist in the manner of the post-war Italian directors such as Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica. But where this comparison fails is that Kiarostami always had to work with fiction, in order to pass the Iranian censors. He could not drive the camera to a scene and point the camera to make a clear and obvious point. He had to be a magician, a master of cloak and daggers.

Although on one of the occasions that I met Kiarostami, he would protest that he never thought of the metaphor when in production. “I think the moment you start to think of the metaphor, your feet won’t touch the ground. The metaphor takes care of itself, you don’t need to film that.”

Born in Tehran in 1940, Kiarostami studied painting at Tehran’s University of Fine Arts. After university, he embarked on filmmaking, specialising in working for films for children. It was at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults that he made his first short films, Bread and Alley (1970) and Two Solutions for One Problem, that he first showed his ability to reduce complex issues down to basic everyday situations. It was with working with children that he also developed a habit for making films where the protagonists were non-actors.

Not that he was averse to using professionals. One of his first feature films, The Report, was the tale of a tax collector who is accused of taking bribes, while on the home front he's dealing with the fall out from his wife's suicide attempt. It’s a traditionally shot film, with conventional set-ups, that now feels almost as though Kiarostami was trying out the classic method, if only so that he knew to discard it.

The director began to get international recognition when he made the Koker trilogy, so called because of a village in northern Iran, where the films were located. The first film made in 1987, Where is the Friend’s Home, took its title from a poem by Sohrab Sepehri, the Iranian poet famed for his love of village life, who was a great influence on Kiarostami. The film was both a bridge for his work from children to adults, and also the first in which he developed his own inimitable style in form and content.

In the second part of the trilogy, Life, and Nothing More... (1992), Kiarostami develops an idea that he seeded in 1990’s Close Up, wherein fact, fiction and analysis all collide. The masterful Close Up is based on the story of a man who pretended to be the filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf in an effort to win favours. Kiarostami, playing himself, confronts him in the film and then introduced the imposter to Makhmalbaf himself, wherein fiction and fact merge, and become a new truth. While in Life, and Nothing More, after an earthquake hit northern Iran, the director returns to Koker, in order to see what has happened with the children who appeared in Where is the Friend’s Home.

The final film in the trilogy, Through the Olive Trees (1994) features a film within a film, in which a film crew go to Koker to make a movie and there get more than they bargained for when it turns out that the lead actor has been in love with the lead actress for a number of years and decides to take romantic action during the course of the film.

He was intrigued by the dramatic changes occurring in society, using a mobile phone to mark out change and the influence of the outside world in The Wind Will Carry Us (1994), in Ten (2002), the conceit is as simple as a woman, played by Iranian artist Mania Akbari, driving other women around Tehran.

In his last films, Kiarostami also branched out into the wider world himself. Certified Copy starred Juliette Binoche in a love story set in Tuscany and his final film, Like Someone in Love, was set in Tokyo and revolves around a prostitute. But it is his work that shines a light on Iranian society for which he will be most fondly remembered as one of the greats of cinema.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments