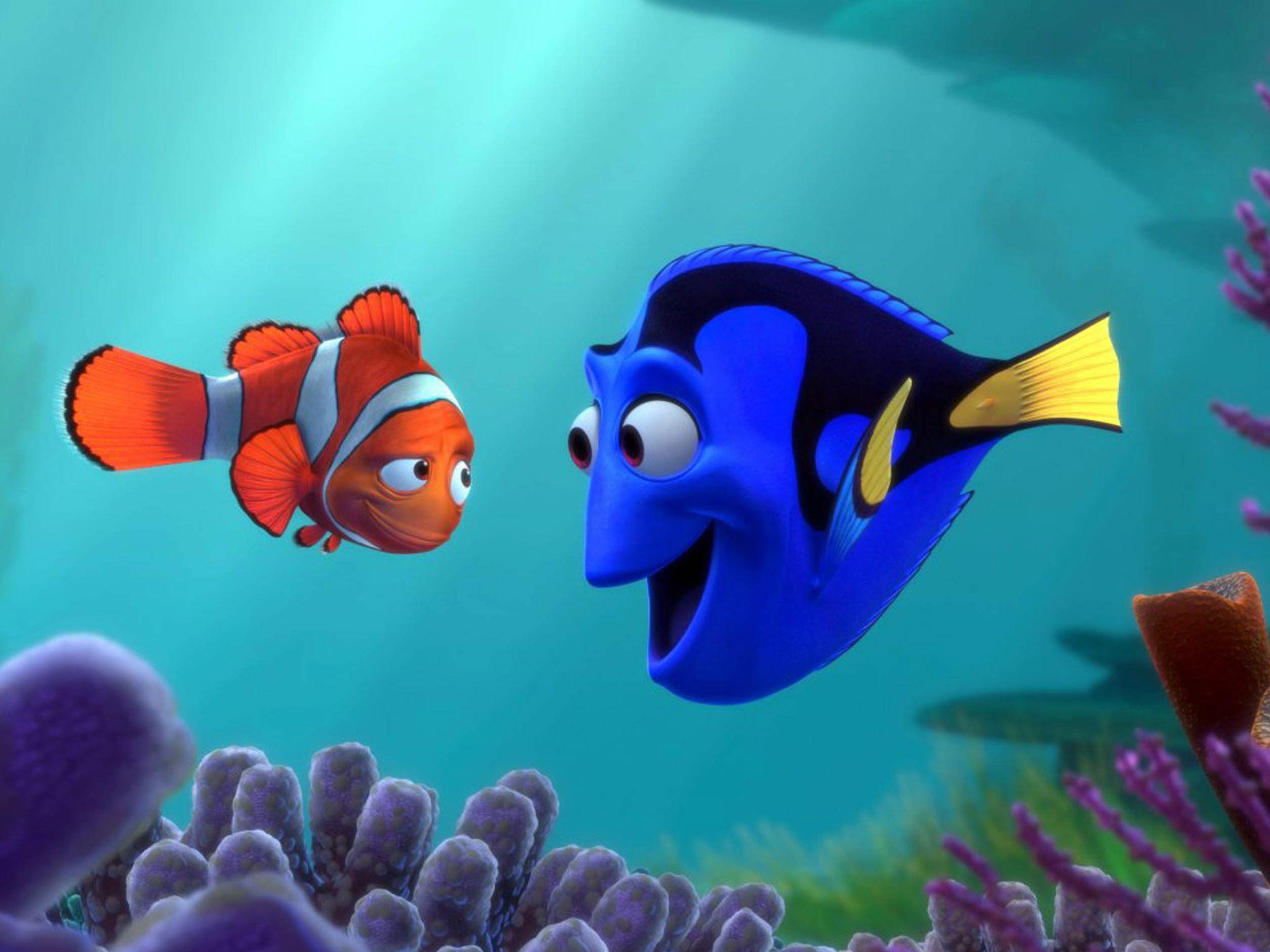

Don't find Dory: Why animals in films should stay in the wild

Being cute characters in animated films can be a catastrophe for some wild animals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most children love animals and movies. And animals in movies. But sometimes these two rather adorable forces collide with devastating effect, when well-meaning families buy pets “as seen on TV”, with little thought for the origins of their exotic new friends or how to care for them.

After the 1990 release of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, river and lakes in the UK were suddenly populated with terrapins the size of dinner plates when overwhelmed owners dumped their once-small pets. In 2003, Finding Nemo – which ironically centred on fish being snatched from the ocean – prompted viewers to buy clownfish, driving wild populations to extinction in the Philippines, as well as parts of Thailand and Sri Lanka. Now, with Disney’s release of the Nemo sequel Finding Dory and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows coming within weeks of each other, conservationists and charities fear history will repeat itself. Animals will be endangered, eco-systems disrupted, diseases spread.

It’s not enough that we’re reducing populations in the wild with man-made climate change, “we’re attacking them from two fronts”, says Dr Judith Lock, from the Centre for Biological Sciences at the University of Southampton. More than a decade after Finding Nemo, a million clownfish are still being removed from wild habitats each year, and sent into captivity. “People have been literally loving the clownfish to death,” says Nicholas Whipps, legal fellow at the US-based Centre for Biological Diversity.

But it’s not just aquatic creatures that have suffered. In 2001, the RSPCA saw a spike in desperate parents looking to re-home owls after the release of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Afetr the 2009 launch of the Compare the Market advert, the charity saw a 191 per cent rise in the number of calls concerning meerkat problems. Meanwhile, a recent study carried out in the UK and US found that movies featuring dogs can affect the popularity of certain breeds for up to ten years.

If such attitudes don’t change, it could spell extinction for the Dory fish, the regal blue tang.

“A spike in the sale of regal blue tangs would be hugely problematic,” explains Nicholas Whipps. At the height of the clownfish craze, 90 per cent were taken from the wild through cyanide fishing, killing coral reefs and other marine-life, and similar fishing methods are used to capture blue tangs. However, unlike clownfish, these cannot be bred in captivity – which means every “Dory” sold must come from the ocean. And what’s more – while inexperienced aquarists will likely place their new pets in crowded, undersized, life-shortening tanks – they need “incredibly large” 180-gallon containers to thrive.

Amid all the talk of death and destruction, however, it is important to remember that film-viewers buy pets because they care about the “characters”. If this enthusiasm could be directed towards conservation, says Dr Judith Lock, from the Centre for Biological Sciences at the University of Southampton, animals would not only be saved but protected in the wild. “Nemo is presented as an individual who needs to be looked after. But this could be used as a conservation hook, looking after the species’ natural habitat.,” she explains.

Failing that, to stem the potential impact, scientists at Flinders University in Australia, where a Saving Nemo campaign is based, are trying to breed blue tangs in captivity. And if that is currently struggling, at least it has encouraged Disney to work with the US Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) on a programme to support tang conservation and produce a responsible fish ownership guide.

Of course, one could try to ban or further regulate exotic pet-keeping. But as Scott Wilson, the Head of Field Programmes at Chester Zoo, explains, the issue is an extremely complex one. “It’s difficult to police,” he says. “There are licensed legal breeders of exotic animals, and there are arguments that captive-breed-sustainable exotic pets are OK to keep. But the fact is that the legal trade is used to hide a huge and growing illegal wildlife trade.”

Wilson argues that public needs to change its attitudes to all exotic animals, and not just those popularised by films: “The illegal wildlife trade is driving species to extinction around the world [so] don’t have your photo taken with that monkey [on holiday], don’t buy that scorpion-in-amber key-ring. And if you really want to get close to the amazing creature you’ve just seen on TV, then visit your local zoo. The trip will also help support conservation and protection efforts.”

As for pets, he says, “Parents should encourage children to stick to cats, dogs and rabbits – and explain why wild animals should stay in the wild.”

‘Finding Dory’ will be released in the UK on 29 July. ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments