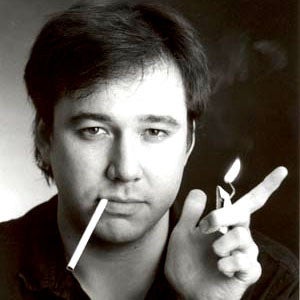

A Brit on the side: Why American comic Bill Hicks felt most at home in the UK

Bill Hicks is a byword for acerbic brilliance in the UK – but he couldn't buy a laugh in his native America. On the eve of a new documentary about the maverick comedian, Peter Watts asks: what makes us love him so?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bill Hicks was, in many ways, the consummate American. The iconoclastic comedian was born in Georgia and lived in Texas, Los Angeles and New York. He smoked like the Marlboro Man, swore like Richard Nixon, joked like Lenny Bruce, died young like Jimmy Dean and dressed like Johnny Cash. But despite a 16-year career that included a dozen appearances on the Late Show with David Letterman, Hicks' career took off only when he came to Britain in 1991. And even now, 16 years after his death from cancer in February 1994, it is Brits who are keeping Hicks' legacy alive. Why do the British celebrate this quintessentially American comedian so intently? And how did he get so popular in the first place?

A film about Hicks is released next month. It's called American and, naturally enough, it was made by two Brits, Paul Thomas and Matt Harlock. Harlock's story stands for many. "I came across Bill at university in the early 1990s, when people were discussing this sensation who had ripped up Edinburgh," he says. "He was a key figure for the student community. On the 10th anniversary of his death, I started putting on Bill Hicks events in London, and lots of people came along."

Hicks' success was partly about timing. He was born in 1961 into a bookish Southern Baptist family and developed an interest in comedy after seeing Woody Allen films on TV. He began doing stand-up at 15 and gigged all over the States thereafter, surviving a bout of drink and drug abuse and never quite breaking into the mainstream – until the Montreal Comedy Festival in 1991. There, Hicks went down a storm and was spotted by Channel 4, which was televising the event after a resurgence of interest in stand-up in the UK. Clive Anderson, the presenter of the channel's popular improv show Whose Line is it Anyway?, went to see Hicks for himself.

"Chris Bould, a director, was making this TV special," Anderson recalls now. "So I watched [Hicks'] set in Montreal and straight away saw that he was a very impressive performer, and a massive presence. He did stuff about politics, war, religion and cancer and could knock your socks off with the power of his delivery. It's not that he didn't have jokes – he did have laugh lines at regular spaces. But he was all about striking an attitude."

Although Anderson's semi-apologetic, ultra-English style was far removed from Hicks' forthright freewheeling rants about drugs and religion, the two got on well. "He was a nice guy. If he liked a joke you made, he wouldn't just laugh, he'd applaud," says Anderson. "It was a charming gesture that didn't quite fit in with his aggressive stance."

By the time Anderson interviewed Hicks on his chat-show Clive Anderson Talks Back in 1992, Hicks' fame had spread thanks to Bould's hour-long Relentless special and sold-out shows at the Queen's Theatre in London.

At the same time, Hicks was having a considerable impact on a younger generation thanks to his regular appearances in the rock press. The writer and DJ Andrew Collins was at New Musical Express when the magazine opened a new front by putting the comedian Vic Reeves on the cover in 1990. "The idea of comedy being the new rock'n'roll was rife, and it held a lot of water," says Collins. "They toured like bands, they had groupies and some of them were quite good-looking. I remember seeing Hicks in the West End. He was a revelation, and he came on [the stage] to the Rolling Stones, so his positioning within rock'n'roll was deliberate and significant. His cassettes circulated around the office, and once Relentless had been on TV, we felt vindicated. Hicks' reputation was built on Relentless. He was so different, so diffident, so frightening, and so dark. He was rock'n'roll without trying, and without it being a pose. This was a long way from Dave Baddiel wearing a hooded top."

Terry Staunton, also a writer at NME, recalls: "The 1980s promise of alternative comedy never delivered. With the exception of Alexei Sayle, the whole Comic Strip crowd embraced the mainstream, and the few political comedians there were tended to be a little one-note. Hicks was the voice of rebellion, and it was a breath of fresh air for us at the NME – who were brought up on articulate and politically motivated musicians such as Paul Weller, Billy Bragg, Elvis Costello and Jerry Dammers – to have someone on our doorstep who could be relied upon to give a good interview."

Two weeks before the NME put Reeves on the cover, it did the same to a dynamic new American band called Nirvana. By 1992, the US invasion of English rock was in full flow and a succession of visceral Yank bands were lumped together under the term "grunge". Hicks, an angry American comedian with a love of rock, was perfectly poised to take advantage of English students' new obsessions.

It helped that Hicks was an extraordinary performer. "He was certainly more challenging than [US rockers] Soundgarden," jokes Collins. "He was mature beyond his years,' adds Anderson. "He had that confidence of somebody who had been around for years – which he had, as he'd run away from home to perform at comedy clubs when he was 16."

Harlock expands on this point. "He appeared here just as he was fully formed. Nowadays, people are aware of comedians at a much earlier stage, but he arrived out of nowhere as a complete package. He'd already done the work and dealt with the problems he needed to surmount."

Hicks once said, "People in the UK share my bemusement with the United States that America doesn't share with itself. They have a sense of irony, which America doesn't have, seeing as it's being run by fundamentalists who take things literally." But this is an oversimplification. After all, there are few things the British like more than jokes about America, especially when they are told by Americans, making Hicks' routines less difficult for English ears. As Dan Hind, the (English) editor of Love All the People: Letters, Lyrics, Routines, a compilation of Hicks' writing, says, "It's an easy sell. Hicks said he was Chomsky with dick jokes, and the British are much happier reading Chomsky than the British equivalent. You can experience that thrill of thinking 'Isn't America terrible?' without having to consider the parallels or our own relationship with American culture.

"A lot of Hicks' comedy was based on a hate-hate relationship with Southern, white working-class or rural culture. He loathed it. And if you imagine a British comic ripping the hell out of the British white working-class, it would be difficult to stomach. I don't imagine that those who enjoy him having a go at rednecks would be anywhere near as comfortable if he was doing the same to our equivalent."

Paul Thomas notes also the simple logistical difficulties of breaking America. "The size of the country is crucial," he says. "In the UK, if somebody makes a splash in Edinburgh, you hear about them in London, but America is so vast, everything is held together by television and if it isn't up there on that screen on prime-time you won't hear about them, even if they are huge in New York."

Hicks himself thought TV went some way towards explaining why he didn't have the same cultural impact at home. "Bill's brother Steve asked Bill why he hadn't kicked off in the US in the way he had here," says Harlock. "And Bill said it was simple: it was because his material was played on prime-time British TV unedited in a full-length set, whereas in America he was given only five minutes on late-night TV, he wasn't allowed to swear and there were other restrictions."

(Famously, his final routine – his 12th appearance – on Letterman, in 1993, was pulled, as network executives found it too offensive. The set, which included an attack on pro- lifers, was finally shown by Letterman last year, when the chat-show host apologised to Hicks' mother for the routine being banned.)

"It wasn't a cultural difference," adds Harlock, "it's just that in the UK we were given full access to who he was. It wasn't to do with our supposed more sophisticated sense of humour or that we 'get' irony, it was to do with the fact that he was able to do his thing in unrestricted surroundings. It came back to the way advertisers and commercial channels have to work, and Bill had a lot to say about advertising. It ended up affecting him directly."

Understandably, Hicks became a keen Anglophile. Before he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in June 1993, he considered moving to England, and even made a pilot "chat-show" for Channel 4. "He spent his last few weeks re-reading Lord of the Rings," says Hind. "There's a lot of piss-taking in his stand-up about England – coming to Hobbitland – but it was informed by a deep love for some aspects of our national culture."

Harlock wonders whether this ultimately would have spelt the end of Hicks' special relationship with the UK. "He had a razor-sharp view of the world, and he used that to scrutinise where he was from, and that would have been the case wherever he ended up. Bill had talked about moving here and you can imagine that, before long, he'd have turned his beam to English society. Maybe we wouldn't have liked him so much if he'd been here a couple of years and started to tear us apart." n

'American: The Bill Hicks Story' (15) is released on 14 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments