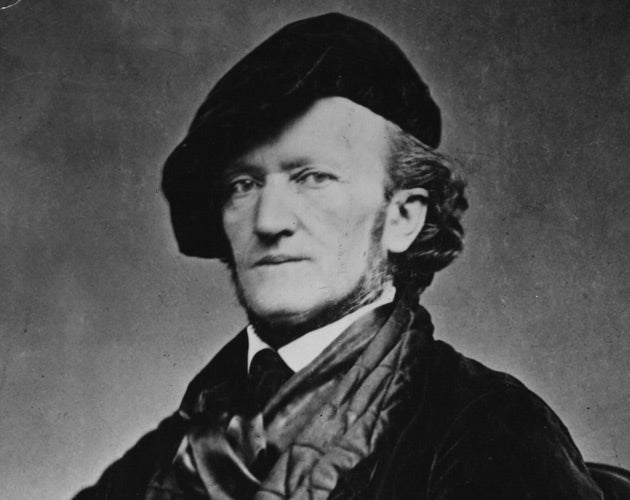

Wagner Lohengrin, Royal Opera House, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A mobile phone and a noisy box of latecomers threatened to violate the sanctity of the Grail so mystically evoked by Wagner in a haze of divisi violins at the start of his Lohengrin prelude.

But not even the ill-mannered among us were going to shake the concentration of Semyon Bychkov and the Royal Opera House Orchestra whose searching and excitingly trumpet-topped account of the score is certainly the most compelling reason for catching this revival of Elijah Moshinsky’s 32-year old staging.

It was the height of minimalist chic back in 1977 with its pure white box and provocative displays of pagan totems and Christian symbols. The best that can be said of it now is that it is pretty much a blank canvas on which to work the mystic drama – or not. The irritating scrims still prevail, preciously suggesting the delicate balance between dream and reality, the corporeal and the spiritual – though the somewhat cheesy projection of Lohengrin’s “swan” crest might now suggest the imminent arrival of Batman on a time-warp from Gotham.

But let’s concern ourselves with the quality of the music-making. Johan Botha is more than equal to the sometimes inhuman demands of the title role. The tessitura is high and often cruelly exposed where Wagner demands pitch-perfect placement of notes plucked unprepared from above the stave. But Botha did well, always striving for quality not quantity, and how he managed it I don’t know, but he saved his most beautiful sound for the 11th-hour revelations of “In fernen Land”, his voice seemingly transfigured by the image of the dove descending to renew the “wondrous power” of the Grail.

In the case of Edith Haller’s Elsa one can honestly say that she has the ideal sound for the role – a full but almost “white” sound with little or no vibrato to corrupt its honesty. But it is a one-colour sound and she noticeably ran out of steam in the big confrontation with Lohengrin, completely flunking the climactic money note.

And Elsa’s nemesis, Ortrud? Well, Petra Lang, with her vivid words and fabulous top, amply demonstrated that there is glamour in wickedness and with her words “I will teach you the sweetness of vengeance” she duly reeled in Gerd Grochowski’s Telramund. Gaunt of stature and voice, he doesn’t quite have the heft for the role’s invective but in chilling unison with Lang they more than gave the Macbeths a run for their money.

One final point: what are we to make of the impassioned kiss between Elsa and her young brother’s return to human form at the close? Has Ortrud’s paganism infected Brabant after all?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments