Rodelina, classical review: Iestyn Davies triumphs in Richard Jones' new version of Handel's opera

Coliseum, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rodelinda may be one of Handel’s most majestic operas, but until Jean-Marie Villegier’s 1998 Glyndebourne production – in which the German countertenor Andreas Scholl first trod the boards – it was scarcely known outside Handelian circles.

Now director Richard Jones and conductor Christian Curnyn are presenting it with a cast headed by the singer who is replacing Scholl as the world’s top countertenor, Iestyn Davies.

The plot begins with the kingdom of Lombardy divided between two warring camps. Grimoaldo drives Bertarido into exile; putting out false reports of his own death, Bertarido returns to rescue his wife Rodelinda and son Flavio; Grimoaldo’s lust for the faithful Rodelinda becomes the motor for a drama in which ferocious violence seems constantly in the offing. All is amicably resolved thanks to a convoluted but psychologically convincing chain of events.

Villegier set the drama in fascist Italy. Jones places it among Fifties Mafiosi, and although they only carry knives this does ensure that the music is not punctuated by gunshots. Jeremy Herbert’s designs divide a cut-away set into two rooms of the gangsters’ fly-blown headquarters. When the action moves outside to Bertarido’s monument the iconography is perfectly observed, with his ‘murder’ reflected in a clumsy amateur painting of the sort to be found in dirt-poor villages all over the Latin world. We see Grimoaldo getting Rodelinda’s name tattooed on his back, while hers bears Bertarido’s name: the protagonists in this dynastic battle may have exalted music, but they’re a very rough lot.

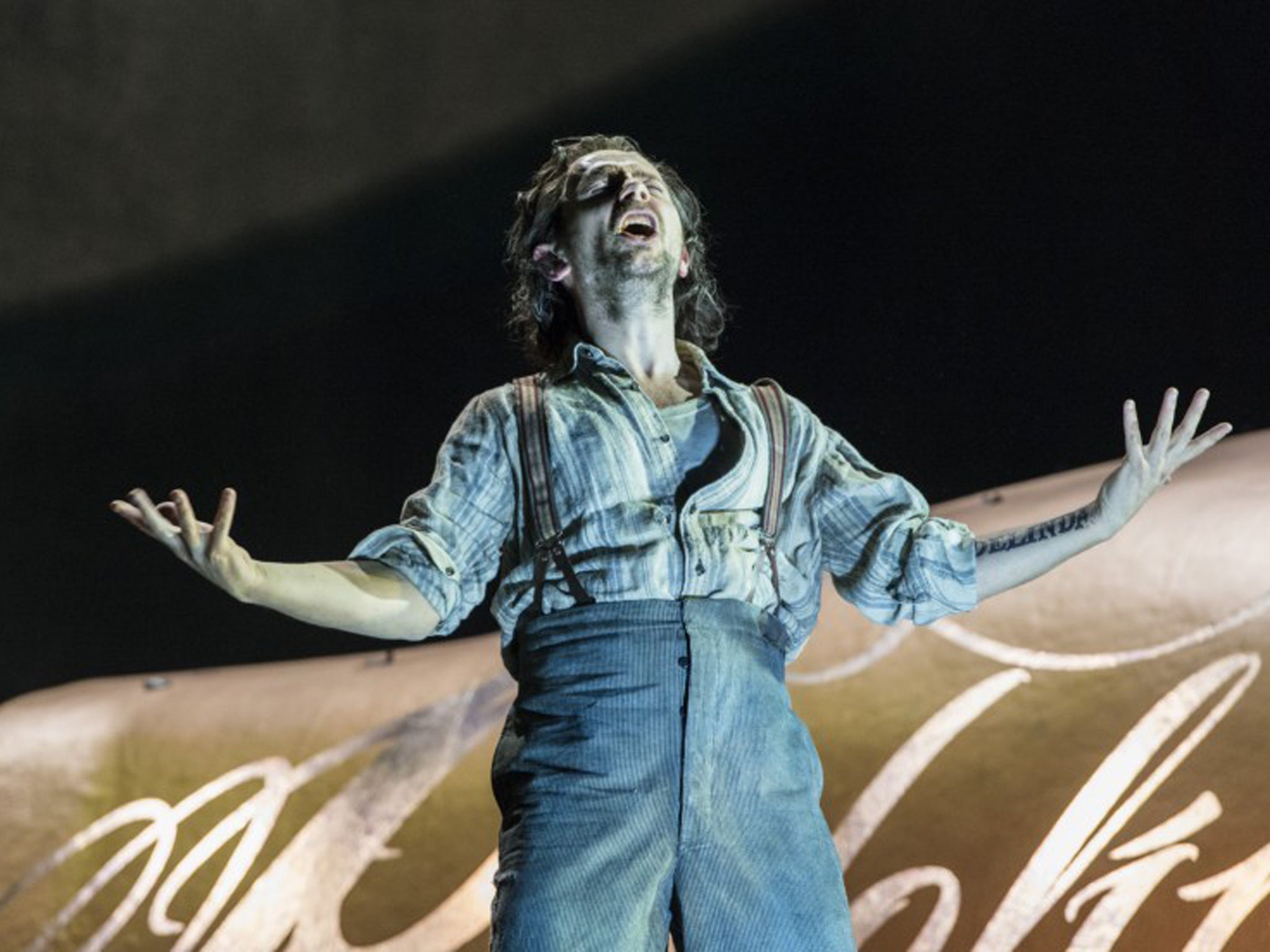

When Davies, as Bertarido, launches into his opening aria of desperate loss, we immediately get the full splendour of his sound; when Rebecca Evans in the title role gives vent to her own desolation, it’s with a full-bloodedness turning to physical fury as she hurls jewels back at her would-be seducer Grimoaldo. And although John Mark Ainsley sings that role with the refined grace we expect of him, he initially seems awkward in his character, as does Susan Bickley in the role of Eduige, whom Grimoaldo has spurned. But Ainsley goes on to delineate Grimoaldo’s descent into madness with a rare cumulative power.

Since this opera is all arias (apart from one duet, divinely sung by Davies and Evans), and since each da capo aria contains several repeats, Jones has developed strategies to deal with what he seems to perceive as the problem of audience-boredom. Some of these repeats are turned into slapstick comedy, while others are taken on a series of treadmills, and yet others with singers pinning up endless mug-shots on walls. The most successful da capo device has Bertarido’s advisor Unulfo (Christopher Ainslie) dressing up as a barman to serve his master who is drowning his sorrows in a neon-lit bar, where the echo-aria ‘Con rauco mormorio’ sounds as plangent as it should.

Immaculately served by Curnyn and his orchestra, Jones’s production refracts the plot’s emotional extremes through too many layers of directorial artifice for them to grip the heart, and he imposes his own comic denouement in which Iestyn Davies revels with his instinctive comic timing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments