Opera review: The Magic Flute

Simon McBurney successfully conveys this work's evanescent mystery

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Simon McBurney is a one-off among theatre directors: there's an untamed wildness about his productions, sparked by a free-flowing imagination and a passionate zest for life. After the homespun surrealism of Complicite, he's pursued an increasingly zigzag course via Russian-Communist hyper-realism and delicately suggestive Japanese theatricality, so it's appropriate that he should make his second foray into opera with Mozart's most unfathomable work.

McBurney finds echoes of Shakespeare's Tempest everywhere in The Magic Flute. Without forcing comparisons, he sees in Sarastro a latter-day Prospero, in Tamino a recognisable Ferdinand, in Pamina a Miranda, in Monostatos a sort of Caliban, and in the three boys a strong hint of Ariel. Admitting that he often feels lost in what he calls the "unpredictable turbulence" of this opera, he promises to "make the music his compass".

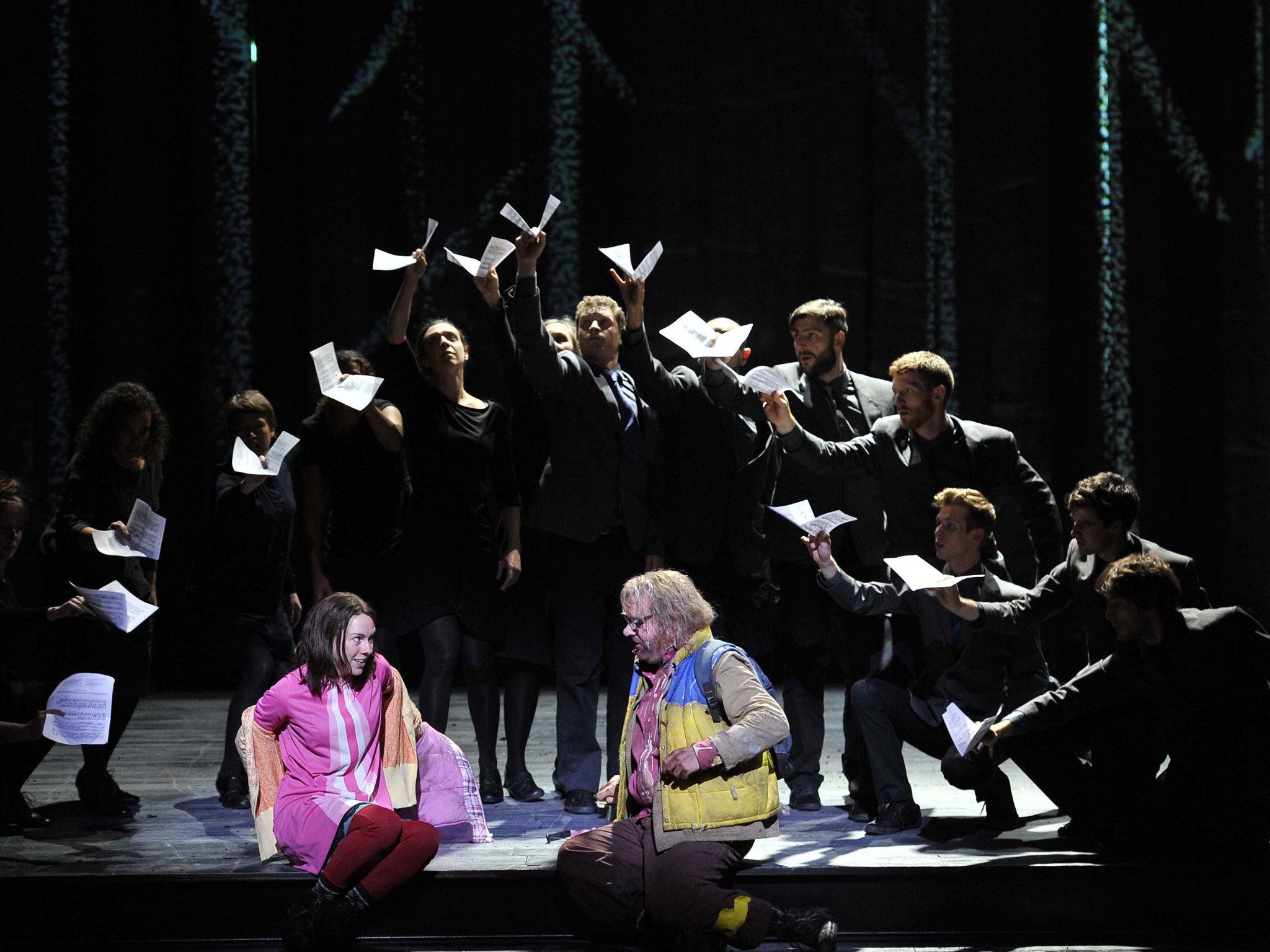

The first thing that strikes you is the way he's changed the performance space, taking away the side-boxes to give a wider stage, and raising the orchestra to a level with the stalls, thus putting audience and musicians into intimate proximity. As the overture begins, a giant hand appears on a screen, chalking the dramatic agenda on a blackboard: with the video artist visible stage-left and the sound-effects artist with her box of tricks stage-right, it's as though we are watching the show being created on the spot. A video of Tamino's serpent snakes through chalked mountains, and he wrestles with it convincingly until rescued by three ladies in military fatigues. The only physical piece of scenery in Michael Levine's designs is a vast suspended platform which is in constant tilting motion; apart from a flock of doves suggested by fluttering sheets of paper, everything else is done with lighting, and images projected onto screens.

McBurney's plausible political subtext had been stated in advance: for him the Queen of the Night, as representative of the dying ancien regime, must be infirm and confined to a wheelchair. But the way Cornelia Gotz sings that role is refreshingly original, a very human mother with an unshowy sweet sound, and leaving the pyrotechnics to take care of themselves. The other roles are no less effectively conceived: Roland Wood's Northern Papageno is a pantomime comedian, but he duets poignantly with Devon Guthrie's pure-toned Pamina. Ben Jonson's homely Tamino is exquisitely sung, and in Steven Page we get an intensely dramatic Speaker, while James Creswell's Sarastro has a marvellously sonorous gravitas. Spirited conducting from Gergely Madaras ensures that everything works musically as it should; Stephen Jeffreys' translation combines Shakespearean borrowings with earthy contemporary wit.

McBurney's stagecraft is at times over-busy and his jokes can be laboured, but the second act he brilliantly hits his stride. He transforms the truth-telling boys into grey-headed ancients, conjures up a convincing modern version of an Enlightenment secret society, and turns the trials by fire and water into extraordinary visual events. This fantastical show will never be anyone’s definitive Flute, but it conveys more of its evanescent mystery than anything else has for a long time. That's quite an achievement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments