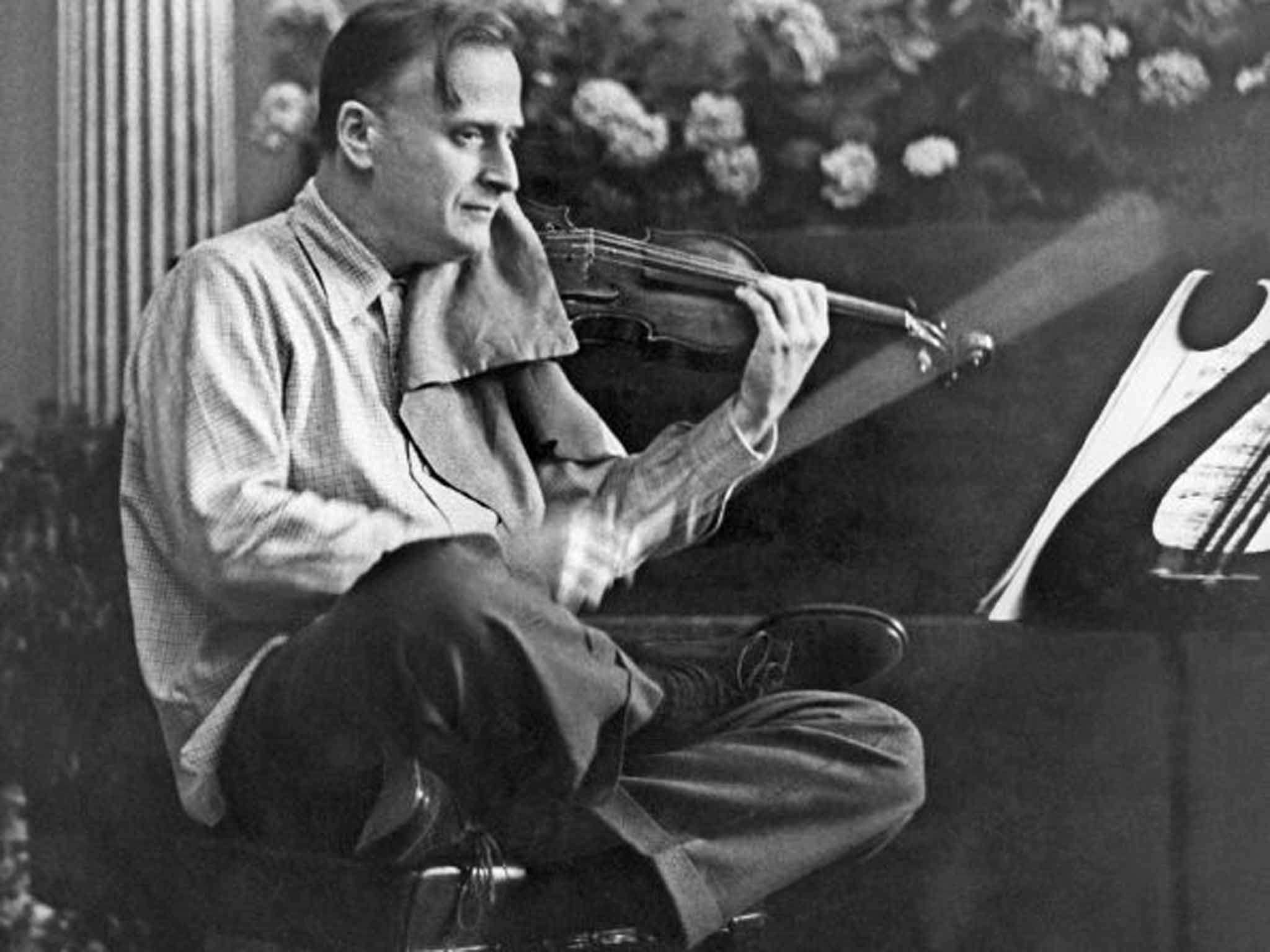

Yehudi Menuhin's centenary year: A maestro with many strings to his bow

As the musical world celebrates Yehudi Menuhin, Jessica Duchen reviews his legacy and explains why he is remembered as far more than a violinist of extraordinary talent

On 22 April 1916, a violinist was born in New York whose artistry revolutionised the world of music. Yehudi Menuhin was more than a great performer; he was a visionary, a pioneer and a humanitarian. Devotees speak of him in saintly terms; detractors branded him an eccentric, a miraculous musician in his youth but arguably less so later; and his family life was undoubtedly complex. Yet his artistic priorities turned out to be far ahead of his time, and perhaps that is why his centenary has such significance.

From the start, there was no doubt that he would be a violinist. His parents, Moshe and Marutha, made certain of that; his mother would lock his younger sister in a cupboard if she disturbed his practising. He was a true prodigy, “a child and yet he was a man and a great artist,” as the conductor Bruno Walter put it after working with him in 1929. He trained with some of the finest musicians of his day: Louis Persinger in his home city of San Francisco, George Enescu in Paris and Adolf Busch in Switzerland. His early recordings, made when he was barely 12 years old, reveal not only an astounding grasp of the mechanics of playing, but a sophisticated musicality worthy of an artist three times his age.

He recorded Elgar's Violin Concerto with the composer conducting in 1932. Aged 19-20, he undertook an extensive world tour; he then had an 18-month sabbatical, after which the focus moved from Yehudi the prodigy to Menuhin the artist. In 1943, Bela Bartók wrote his Solo Sonata for him – perhaps the 20th century's greatest work for unaccompanied violin.

During the Second World War Menuhin frequently performed for the troops in Britain and Europe. When he and Benjamin Britten played together to an audience of liberating troops and surviving inmates at Belsen, the experience left a profound, troubling impression on him – which nevertheless confirmed for him music's potential to soothe and heal the soul.

Menuhin became fascinated with yoga when he toured India in 1952 and adopted as his teacher BKS Iyengar – whose system became widespread in the west largely as a result. He met, too, the great Indian classical musician Ravi Shankar, who became a lifelong friend; their collaboration made history, bringing together two venerable yet deeply contrasting traditions. “The whole world knows Yehudi as a very special human being, but to me he is just my dearest friend,” Shankar told The Independent in 1995. Menuhin also enjoyed a spirited partnership with the jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli. He was thus one of the first classical performers to embrace other genres of music – something that has become increasingly vital to the artform since the 1980s.

In 1963 Menuhin founded the Yehudi Menuhin School, aiming to offer a specialised education to gifted young musicians, regardless of ability to pay; inspiration came from the Central School for Young Musicians in Moscow (and Russian ballet schools, too – Menuhin's second wife, Diana, had been a dancer). The school absorbed his personal philosophies; everyone did yoga and there was an emphasis on healthy food. Over the year its students have included such luminaries as Nigel Kennedy, Melvyn Tan, Tasmin Little, Alina Ibragimova and Nicola Benedetti.

Enchanted with the Alpine landscape around the Swiss village of Gstaad, Menuhin established there the Gstaad Menuhin Festival and Academy, and remained its artistic director for some four decades; it is still flourishing now. In Switzerland, too, he founded the Menuhin Music Academy in 1977, a centre that continues to expand in exciting new directions. In 1983, he devised a violin competition significantly different in model from others: it focuses on younger artists aged under 22, and moves to a different country each time it is held. This year it returns to Britain to mark Menuhin's centenary.

But perhaps the most inspiring of all Menuhin's initiatives is Live Music Now, a charity that sends young musicians out into the community to play to those whose lives are “challenged due to illness, disability, poverty or social disadvantage”. Its performances have reached more than two million people in settings from village halls to hospitals to prisons; and its principles underpin the boom in community work in musical organisations throughout Britain, and increasingly abroad.

Now anniversary events are happening en masse: the violinist Daniel Hope, a Menuhin protegé, has made a personal CD tribute (on DG); the Menuhin Competition London takes place in April; and Warner Classics is launching a collection of 80 CDs, 11 DVDs and a book for the occasion, including numerous previously unreleased recordings.

But Menuhin, who died in 1999, must have the last word: “Music, amongst all the great arts, is the language which permeates most deeply into the human spirit, reaching people through every barrier, disability, language and circumstance. This is why it has been my dream to bring music back into the lives of those people whose lives are especially prone to stress and suffering … so that it might comfort, heal and bring delight.” If you have ever doubted that one musician can change the world for the better, Yehudi Menuhin offers solid proof.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks