Why it's high time UK concert programmes opened their doors to music beyond the Western tradition

The British classical-music establishment is full of complacent cultural imperialism. Britain is now a very multi-ethnic society, but you’d never know that from its concert halls. There’s an increasingly need for the other classical musics of the world to be given their proper place in UK concert programmes, says Michael Church

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

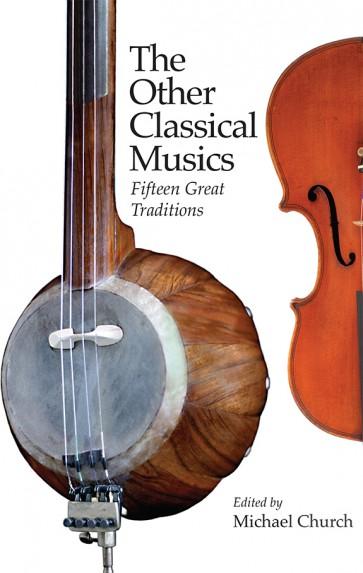

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Church’s new book The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions has won a Royal Philharmonic Society award. Here he explains how the book came about, and why its message is now so important:

My love-affair with non-Western music began half a century ago, when I heard Ravi Shankar make his London debut at the Royal Festival Hall. It certainly helped that raga was cool – this was the mid-Sixties, when we were all wearing beads, banning the bomb and smoking pot, and the slowly unfurling beauties of Hindustani classical music made the perfect soundtrack to our nocturnal confabulations amid clouds of Oriental incense.

But it wasn’t just exotica: I loved that music for itself. And it didn’t in any way conflict in my mind with the music that was already my passion – Monteverdi, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin; it simply seemed to offer an additional musical path down which I could go. And as time went on, I found myself falling in love with a whole series of different musics – Georgian, Albanian, Vietnamese, Kazakh – but as a classical-music critic, I was very much out on a limb. My fellow critics regarded my extra-curricular obsession as a weird eccentricity: as one eminent critic put it, after I’d tried to explain to him why Japanese gagaku was so fascinating: “But it’s all just folk music, isn’t it?” Never mind that gagaku was an elaborate form of court music that Japan had inherited from the courts of ancient China, and which had changed very little in 1,000 years: this was a musical representative of the British Empire speaking, for whom the map of the world was still painted red.

In 1987 a group of frustrated record-company executives came up with the phrase “world music” as a way of persuading record shops to find space for their non-European wares: they were immediately successful, and the subsequent world music boom caught on all over Europe and America. BBC Radio 3’s World Routes brought the music of Cuba, Senegal, Portugal and many other countries into every British home. But that phrase “world music” was itself problematic: a relic of empire, implying that all music that was not European-classical (or rock, pop, or jazz) belonged in an undifferentiated bundle. And the phrase was a nonsense, because all music is world music.

Over the years I had tried to persuade a series of Proms directors to open their doors to music beyond the Western tradition. But each in turn gave the same response: the Proms are a celebration of “our music”, and that’s what they must remain. And to whom was that cosy little “our” referring? To middle-aged white European males, all of whom had grown up in the European-music tradition. Some years, in a condescending bit of box-ticking, they might put on what they called a “world-music Prom”, but these events were always rough stuff, presented with bog-standard amplification. Although Ravi Shankar himself had made Proms appearances in earlier days, the BBC has never officially recognised that the world boasts many other classical traditions besides that of Europe.

Finally, out of sheer frustration, I decided to call together a team of experts to create a book that would describe those traditions. And what we discovered, when the book was written, was that there were a great many congruences across cultures. One of the most striking of these was that all classical musics are intimately connected to religion. Another was the fact that almost all are based on improvisation – European music, which is based on notation, being the exception. This is swings and roundabouts: notation has allowed Western composers to create their extraordinary feats of musical architecture, but their concomitant loss of an ability to improvise has meant that they are denied that well of inspiration that allows musicians in other cultures to speak so directly from the heart to the heart. But the most significant finding of all was that European music has no monopoly on sophistication: the polyphony of the Aka Pygmies in the Congo is as rhythmically and melodically complex as anything by European modernists.

The book’s enthusiastic critical reception – now crowned by the RPS award – suggests that it’s now making a dent in the British classical-music establishment’s complacent cultural imperialism. And the way things are going, it certainly needs to. Britain is now a very multi-ethnic society, but you’d never know that from its concert halls: it’s still possible to go to a symphony concert in London, or Liverpool, or Manchester, and not see one single minority-ethnic face in the auditorium. We do at last have some ethnic diversity on stage, but there’s almost none in the stalls.

Meanwhile, the flow of migration from the world’s trouble-spots means that there’s an increasingly pressing need for the other classical musics to be given their proper place in concert programmes. Britain is already host to many exiled diasporas, and what makes exiles feel at home – what makes them feel less like outsiders – is their music. In March the Wigmore Hall hosted a concert of Afghan classical music, and its auditorium was filled to bursting with people from Central Asia; in December it will host a concert of Syrian music. The new Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg will be holding a festival of Syrian music. How long will it be before the Barbican, the Southbank Centre, and the BBC Proms follow suit? Not too long, I hope.

The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions, edited by Michael Church, is published at £25 by the Boydell Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments