Salomé's feminine wiles have inspired writers, painters and musicians for 2,000 years

Now audiences can meet the Biblical femme fatale in two new stage and screen projects. Boyd Tonkin examines her lasting allure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You just can't keep a bad woman down. In the case of Salomé, an archetype of subversive sexuality since the first century AD, she never seems to stop unveiling, and re-veiling, herself.

Sometimes a vixen, sometimes a victim, and often an alluring blend of both, she has stalked the imagination of writers, painters and musicians for almost two millennia. Oscar Wilde gave the desire-crazed princess of Judaea one definitive makeover when he wrote his florid one-act play about her in (of all places) Torquay in 1891-92. A decade later, composer Richard Strauss saw a German version of Wilde's work in Berlin. Thanks to a revolutionary opera crammed with jarring, lurid sensuality, he created a further classic incarnation of the virgin-vamp.

Over the coming weeks, audiences will have the opportunity to meet the moonstruck minx and what conductor Donald Runnicles calls her "ultimate dysfunctional family" across a variety of media.

Tomorrow, Runnicles brings the Deutsche Oper from Berlin to the Royal Albert Hall for a BBC Proms performance of Strauss's incandescent opera, with Swedish soprano Nina Stemme in the supremely demanding title role. The Edinburgh-born maestro, music director at the Berlin house since 2009, tells me that Stemme "will bring her own personality and remarkable artistry" to a role of high risks and generous rewards. On both theatrical and operatic stages, it has drawn star after star to its curdled eroticism and heady cocktail of erotic, religious and even political power.

As for Wilde's drama, one of the latest icons to take the veil is Jessica Chastain, Hollywood royalty herself after her performances in films such as Zero Dark Thirty and The Help. After seeing Chastain play the part on stage in Los Angeles in 2006, Al Pacino not only directed a film adaptation with her. In the manner of his earlier excursions into Shakespeare's Richard III and The Merchant of Venice, he embarked on a documentary about the work and its place in Wilde's life and art. The resulting double-bill, Salomé & Wilde Salomé premiered at the Venice film festival in 2011. It will play again at the BFI in London on 21 September. The films will be streamed live into cinemas across the country, along with a conversation between Pacino and Stephen Fry – who himself acted as Wilde in Brian Gilbert's 1997 biopic.

It says a lot about the aesthetic pull of the femme fatale that so much febrile artistry has descended from a few enigmatic verses in two gospels. St Matthew gives the basic treatment, as the stepdaughter of Herod, Tetrarch of Galilee, makes a demand that her stepdad can't refuse.

"But when Herod's birthday was kept, the daughter of Herodias danced before them, and pleased Herod. Whereupon he promised with an oath to give her whatsoever she would ask. And she, being before instructed of her mother, said, Give me here John Baptist's head in a charger. And the king was sorry: nevertheless for the oath's sake, and them which sat with him at meat, he commanded it to be given her.

St Mark fleshes out Herod's fatal undertaking: "The king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt... And he swore unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom." Salomé craves not land or jewels – but the chaste prophet's life. The striptease routine of the seven veils, by the way, does not enhance the dance until a 19th-century poem by Arthur O'Shaughnessy.

In the New Testament, the pirouetting princess whose wiles deliver the Baptist's head on a silver platter lacks even a name. That comes from the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, writing in the AD90s. He names the daughter of Herodias as Salomé, and adds the horror of both incest and divorce that underlies her power to disturb.

Her mother Herodias, Josephus remarks, had "married Herod the Tetrarch, her husband's brother by the same father... to do this she parted from a living husband." As in Hamlet, bad faith and unruly lust in the senior generation frame the crazy conduct of the juniors.

Donald Runnicles reflects on the "somewhat warped relationship" between stepfather and stepdaughter. He thinks of Salomé as "a child who is, on some level... brought up in the wrong way. The results of that can be what we experience in [Strauss's] opera."

Jessica Chastain, interviewed at the time of her LA performance, commented that, raised in a family of irresponsible hedonists, Wilde's Salomé initially "decides that she's going to be pure. She's going to be a virgin, and she won't be sullied by all that's going on around her. Then she meets John the Baptist, who is all that she aspires to be: this chaste, beautiful man who is condemning her mother". You could, if you wished, blame the parents.

Medieval culture tended to simplify these tangled dynamics into a straightforward fable of female lust and the wreckage it leaves in its wake. Salomé's dance appears on a 13th-century bas-relief at Rouen Cathedral; she is acrobatically walking on her hands. She might be a very bad girl, but the sculptor gives her a skittish side as well. Renaissance painters preferred the bloody severed head of John, as in Caravaggio's grizzly masterwork (now in the National Gallery). Look at it today and, like it or not, the sands of Syria and Iraq will unavoidably come to mind. In contrast, Bernardino Luini has Salomé serve up the post-decapitation morsel with the deadpan look of a bored waitress ferrying the special of the day to diners.

The Rouen frieze helped to arouse the interest of Gustave Flaubert in Salomé and her accursed folks. "Herodias", one of his Three Tales published in 1877, set in motion the parade of late 19th- and early 20th-century artworks that would define the princess, her dance and her demand as the quintessence of Decadence.

The Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau depicted her twice in the 1870s. In Joris-Karl Huysmans's classic Decadent novel Against Nature (1884), the Moreau version of Salomé obsesses his neurasthenenic hero Des Esseintes. In the painting, Des Esseintes "at last saw realised the superhuman and exotic Salomé of his dreams. She was no longer the mere performer who wrests a cry of desire and of passion from an old man by a perverted twisting of her loins... She became, in a sense, the symbolic deity of indestructible lust, the goddess of immortal Hysteria, of accursed Beauty".

Huysmans gave Wilde his cue, along with the perfumed and luscious style of symbolist playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. Famously, Wilde wrote Salomé in French – a French as baroque and feverish as his drama's mood: "Ah! thou wouldst not suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Jokanaan. Well! I will kiss it now. I will bite it with my teeth as one bites a ripe fruit."

The Lord Chamberlain quickly banned the play, ostensibly because stage depictions of Biblical characters remained unlawful. A legal public performance in Britain, as opposed to the several club outings in the 1900s, would have to wait until 1931.

In spite of this censorship, the play proved a milestone for Wilde. He did not actually write it for his friend Sarah Bernhardt, but once the legendary French diva had read it, she wanted to act Salomé. Wilde later wrote that, "The fact that the greatest tragic actress of any stage now living saw in my play such beauty... always will be a source of pride and pleasure to me". Salomé also served to cement Wilde's fatal affair with Lord Alfred Douglas. "Bosie" translated it into English, rather badly, and the smitten author had to correct many schoolboy faults himself before it was published in Paris in 1893.

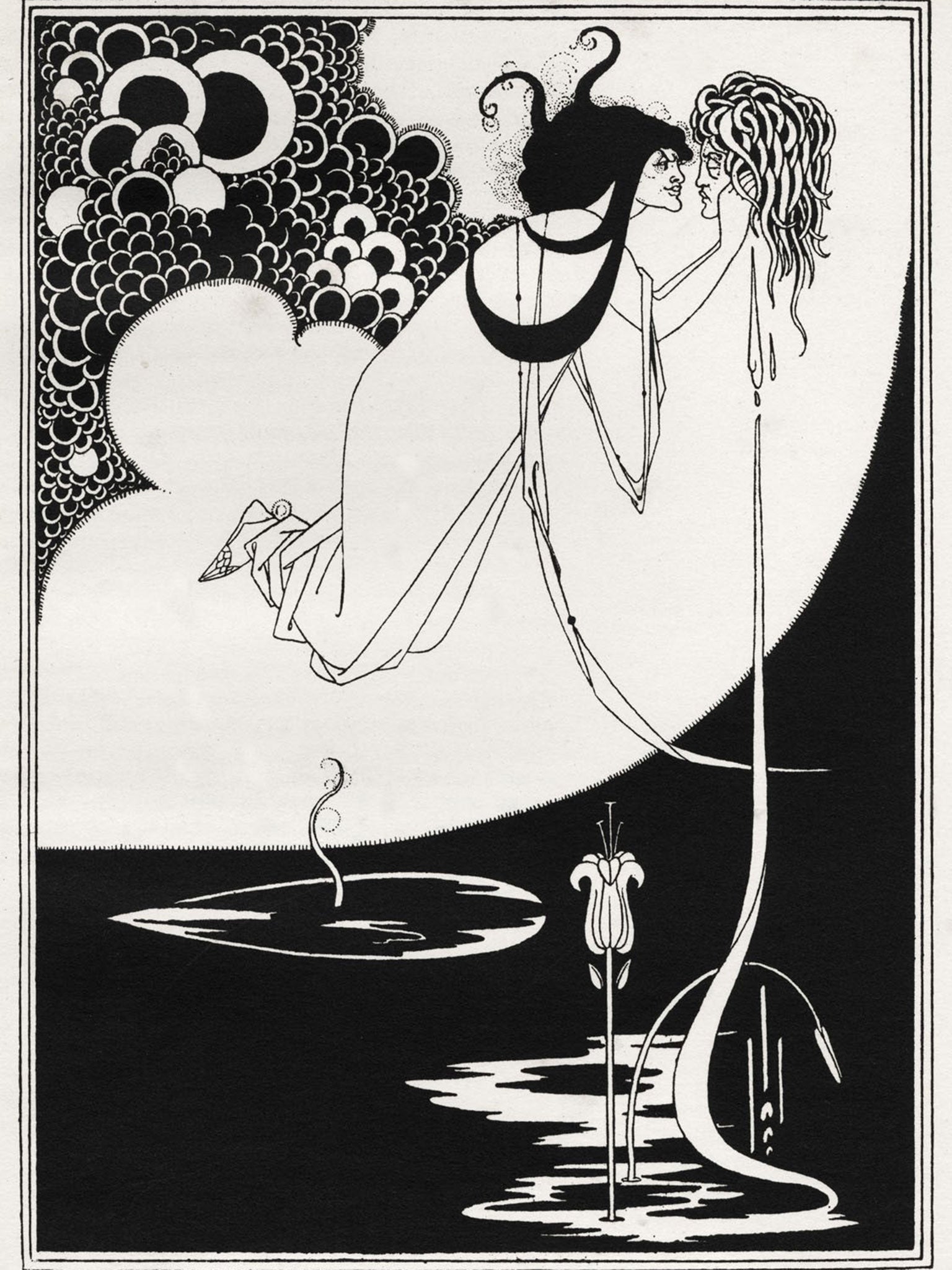

The following year, Aubrey Beardsley's 16 mischievously sexy illustrations to Salomé sealed another crucial artistic partnership for Wilde, even though he complained: "I admire, I do not like Aubrey's illustrations. They are too Japanese, while my play is Byzantine." True, the Beardsley drawings sport a cool, erotic wit at odds with the sulphurous pseudo-Biblical diction of the play ("Neither the floods nor the great waters can quench my passion. I was a princess, and thou didst scorn me. I was a virgin, and thou didst take my virginity from me. I was chaste, and thou didst fill my veins with fire").

By the time that Salomé (without Bernhardt) reached the stage in Paris in 1896, Wilde had undergone his three trials and languished in Reading Gaol. When, in early 1897, he addressed Douglas in his confessional testament De Profundis, he still viewed the play as a turning-point in his career, as much spiritual as stylistic. In hindsight, Wilde detects in it the "note of doom" that runs across his work "like a purple thread... one of the refrains whose recurring motifs make Salomé so like a piece of music and bind it together as a ballad".

By 1905, Strauss had teased the potential music of the play into raucous, swooning life. Premiered in Dresden, and soon performed in more than 50 other houses, the operatic Salomé and her unearthly, exotic sound-world inaugurated a century of doomed and dangerous heroines. Donald Runnicles, who has known this score for 30 years, especially admires how Strauss "evokes the Biblical world with this remarkably, vivid, sensual, colourful orchestration". His delirious Dance of the Seven Veils fast became a famous showpiece that bred dozens of adaptations, both serious and sleazy, in clubs or cabarets.

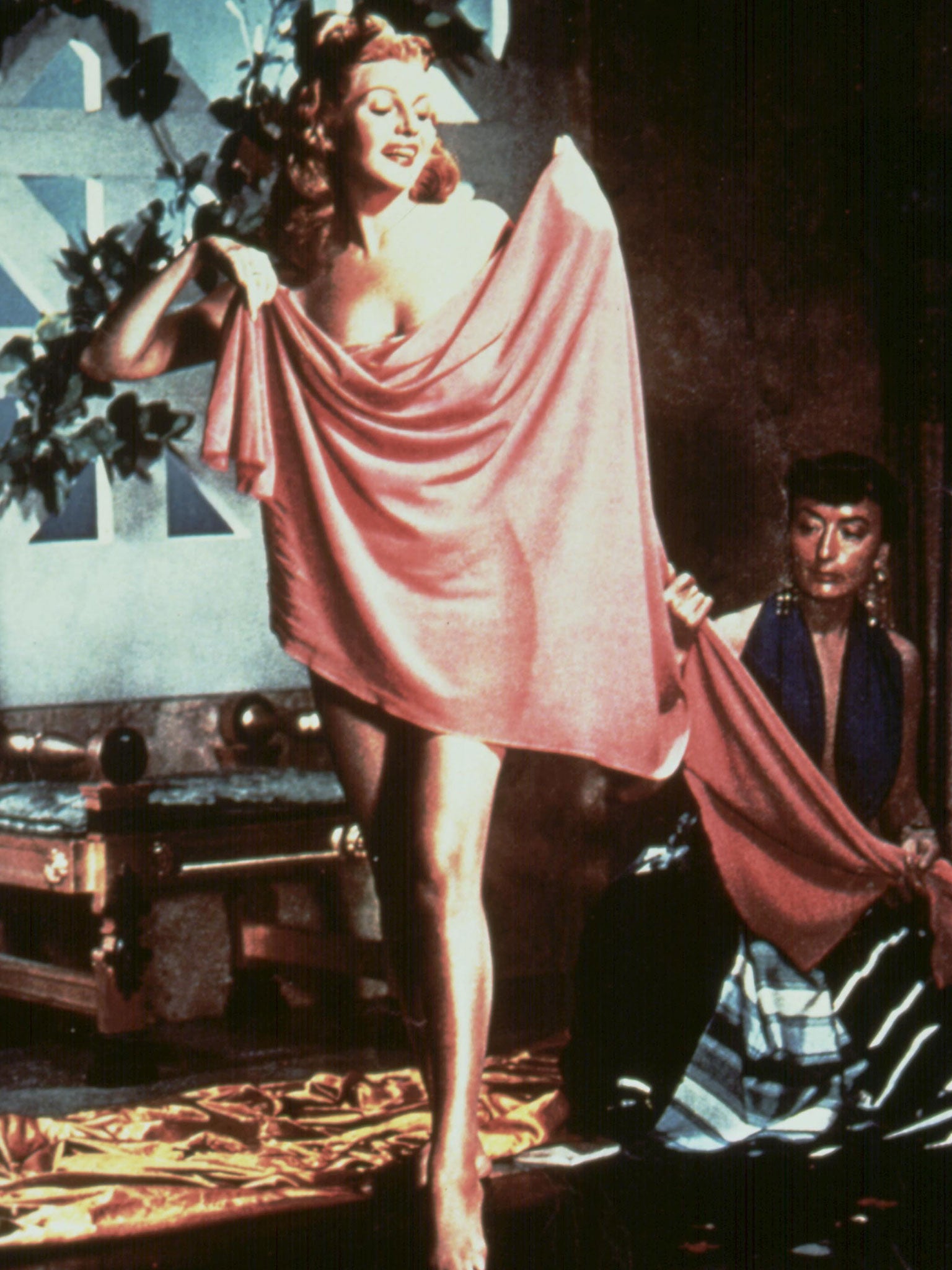

In 1918, the Canadian actress and dancer Maud Allan, well-known for her own creative take on the play, came under attack from the gay-hunting MP Noel Pemberton Billing. After unleashing a witchhunt against male homosexuals in high places, Billing then broadened his field of fire to denounce "the cult of the clitoris". Allan sued for libel, but lost after a sensational trial. Clearly, the stroppy princess and her modern avatars could still turn the head – or scramble the brains – of the most upright sort of chap. Salomé continued to twirl and shed: even Rita Hayworth cast her rags to the wind in a 1953 Hollywood epic.

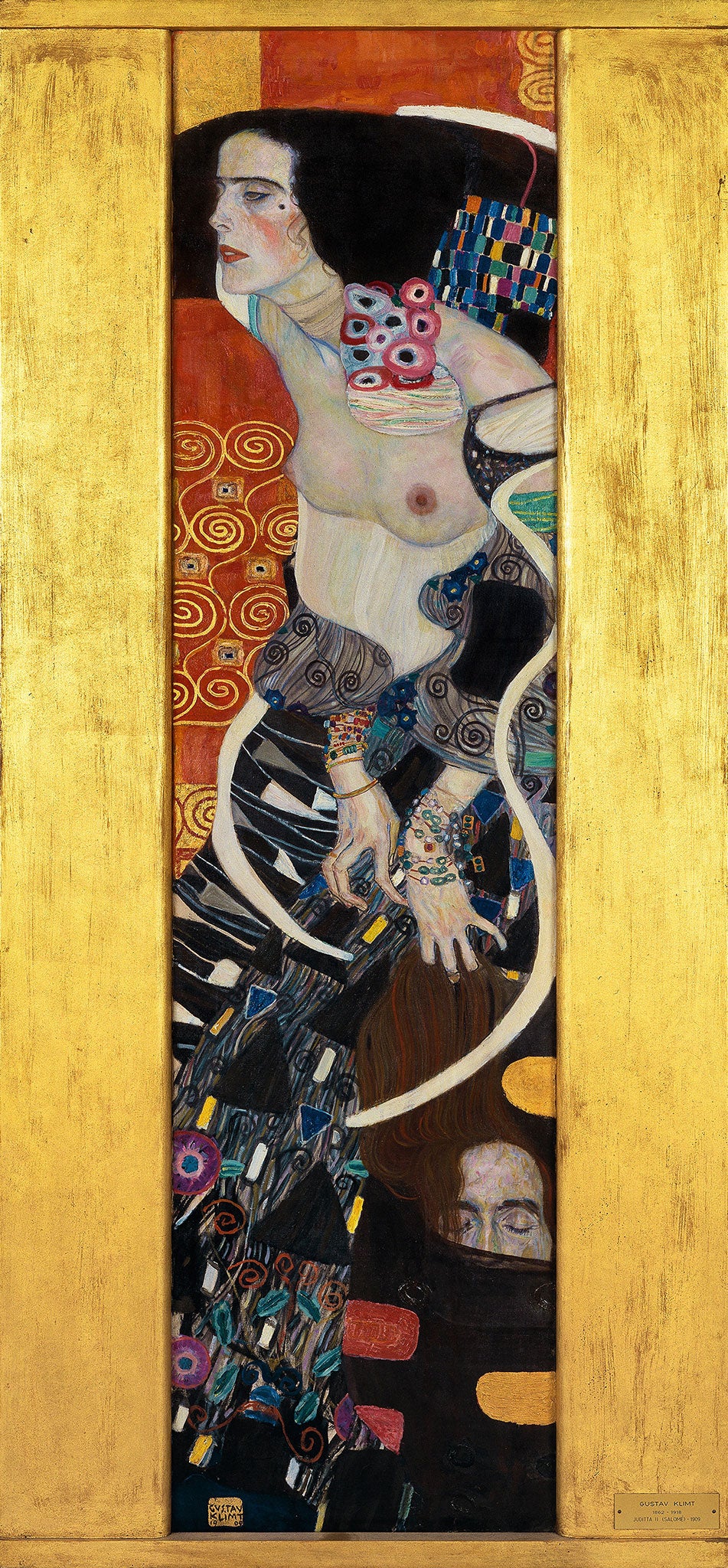

For Runnicles, Strauss's music "starts where the words leave off". The composer packs "tension, beauty and violence" into a trail-blazing score that dragged opera into the haunted world of Freud or Klimt, its music swept and torn by unconscious desire. Strauss's Salomé ends with a crashing dissonant chord, as alien and unsettling as the passions of its heroine. Runnicles, who is "excited and proud to be bringing this great opera company to London", finds the theme and Strauss's approach to it inexhaustible: "What you have on the page is a blueprint. It's up to you to breathe life into it."

Al Pacino, who acted in three stagings of Wilde's play before he filmed it, also discovered that the princess will not let her interpreters go. He first encountered Wilde's play via Steven Berkoff's 1988 London production, when (as he said at the time of his film's premiere) "I felt connected... to something that I hadn't been connected to in a long time of going to the theatre". Salomé, Pacino affirmed, seduces even as she shocks: "There is something in the play that mesmerises, keeps you attentive even if you don't like it."

Runnicles underlines that we feel "sympathy and warmth" even as she exacts her terrible revenge on the purity of Jokanaan. He feels that, in play and opera, we can sense the creator "almost admiring if not loving this woman".

Now, on stage and screen, we have another chance to get behind her veil.

The Deutsche Oper production of Strauss's 'Salomé' is at the BBC Proms at 7.30pm tomorrow, broadcast live on Radio 3. Al Pacino's 'Salomé & Wilde Salomé', with a conversation between Pacino and Stephen Fry, will show on Sunday, 21 September at the BFI Southbank, with live screenings nationwide

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments