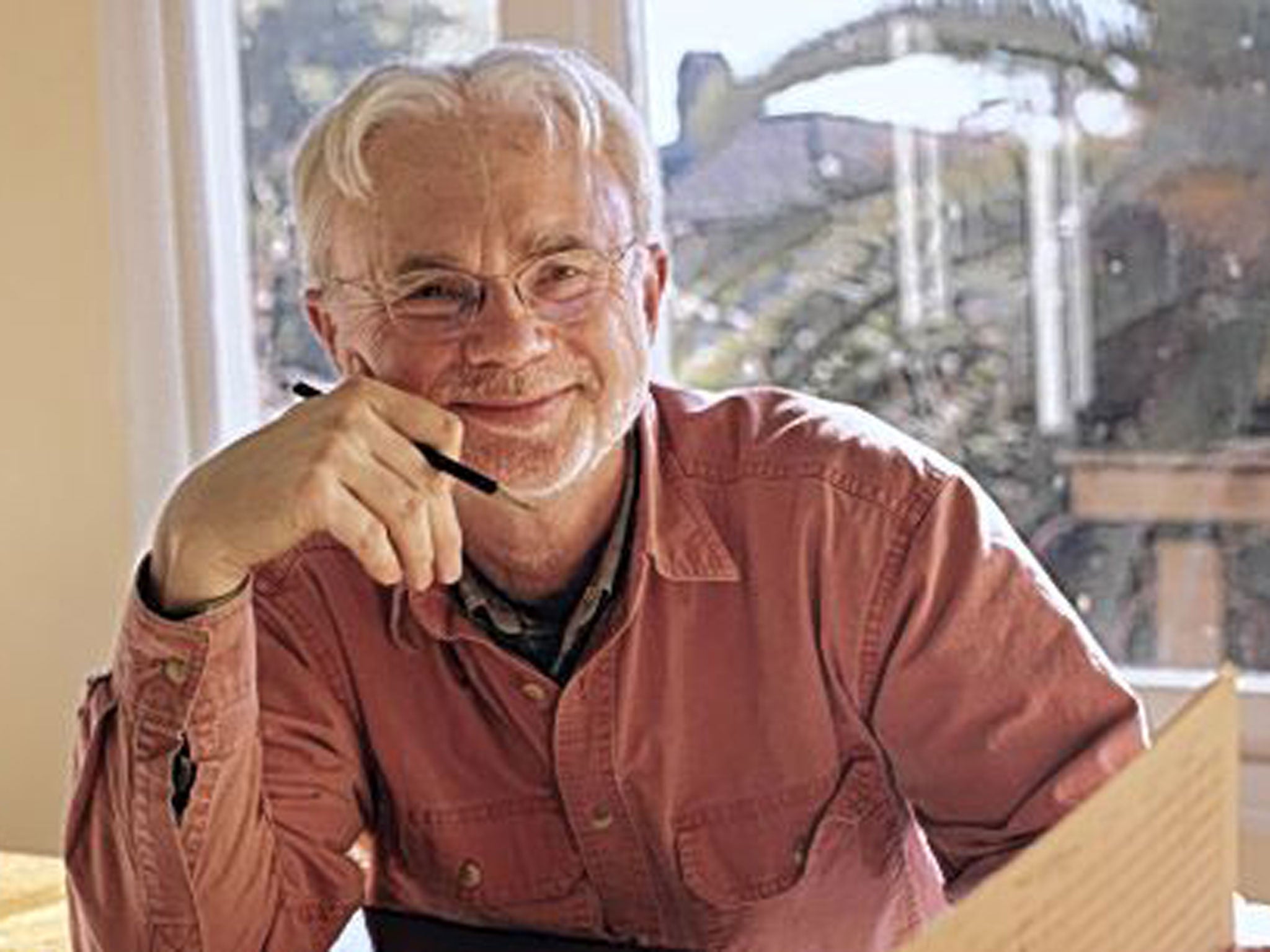

John Adams: A composer scavenging for his art

Having helped to revolutionise composition in the US, John Adams talks to Jessica Duchen about stealing from Beethoven to create his latest piece

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Adams is at the forefront of a generation that is revitalising the orchestral repertoire for a new century. One of the triumvirate – with Philip Glass and Steve Reich – who revolutionised composition in the US after the advent of minimalism, his vivid style seems the authentic voice of his time and place, northern California: colourful, cosmopolitan, airy and afizz with energy.

This month, the San Francisco Symphony, the St Lawrence String Quartet and the conductor Michael Tilson Thomas bring his Absolute Jest to London, a piece in which Adams turns his startling freshness towards Beethoven. Fragments of the latter's scherzos ripple through it, distorted as if by "a hall of mirrors". "We composers, we're scavengers," Adams suggests. "Beethoven was a scavenger, Bach too – that's one of the joys of being creative. Stravinsky is rumoured to have said that 'a good composer borrows, a great composer steals'. That may be apocryphal. But it's not without truth."

In his youth (he is 67), it took Adams some time to find his musical feet in what seemed a proscriptive modernist environment. "I felt that composers like Pierre Boulez and Milton Babbitt represented an expressive cul-de-sac," he says. "Minimalism showed me that there was a way out of that: it had many of the essential elements of musical experience – tonal harmony and pulsation, for instance, and you could build large structures with it.

"But eventually I realised that the style's pure form was too rigorous for my musical personality. That's why I became the composer I am: less stylistically pure and less orthodox in my thinking, more embracing and more unpredictable."

Today's scene presents other difficulties, he adds: "On the one hand there's no oppressive orthodoxy of the kind I had to cope with in my twenties; on the other hand, there are no templates. Each composer has to invent his or her own voice; we're staring into the void every time we start a new piece. To be a composer now is therefore a little more existentially risky than it used to be."

Adams, much celebrated for three operas – Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer and Doctor Atomic – seems increasingly attracted to traditional "templates". He is writing a large-scale violin concerto entitled "Scheherazade.2", while the first recording of "The Gospel According to the Other Mary" is released this month, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel – the closest thing he has yet composed to a Bachian Passion.

"There is a sense in which these almost Platonic forms just work," he comments. "I remember the 1960s when people announced that the novel was dead and all these structures exploded – that was the voice of the future. John Cage was saying the same about musical forms and young artists read that with both a fizz of excitement and pure dread. Today the novel is back; people are less worried about the form and more concerned about the content. It's possible to draw an analogy with that and classical music."

Compared to most contemporary composers, Adams has a massive audience. Last year the Southbank Centre's celebration of the 20th century, The Rest Is Noise, closed with a sold-out performance of his Christmas oratorio, El Niño – a retelling of the nativity story, replete with poetry in Spanish and ending not with grand hallelujahs, but with a guitar and children's voices musing on the word "poesia". That unquenchable vitality keeps drawing Adams's fans back to his music. To judge from his packed schedule, there is plenty more on the way.

San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas & St Lawrence String Quartet, Royal Festival Hall, London SE1 (0844 875 0073) 15 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments