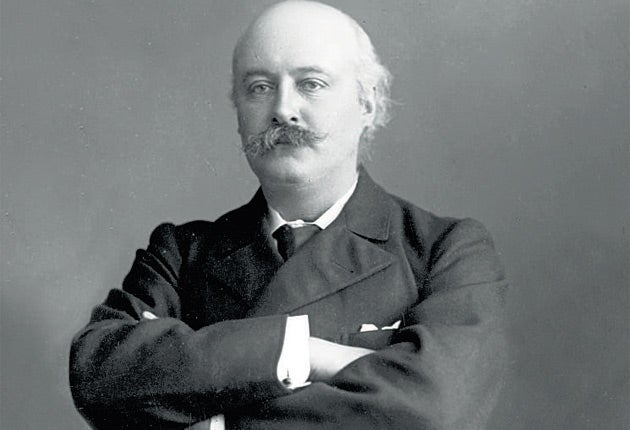

Hubert Parry - Royal appointment for a radical voice

Hubert Parry composed Jerusalem to support suffragettes not rouse patriots. Jessica Duchen uncovers a misunderstood man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Kate Middleton sailed up the aisle at Westminster Abbey to marry Prince William, there was no mistaking the sonic grandeur accompanying her progress. The anthem "I Was Glad" by Sir Hubert Parry (1848-1918) was tailor-made for right royal occasions – it was written for the coronation of King Edward VII. Now its sudden popularity – along with the fact that Parry wrote "Jerusalem", one of the best-known melodies in the land – is helping to restore the composer's reputation as a British musical hero. He is apparently a favourite listen for HRH Prince Charles: in a new documentary for BBC4, entitled The Prince and the Composer, the Prince of Wales himself explores Parry's life and times along with the director John Bridcut.

Parry's ceremonial, dyed-in-the-wool fustiness crystallises all that we love – or loathe – about "English" music. Often it seems to have "conservative establishment privilege" written all over it. That, though, can be seriously misleading. The Royal Wedding may have been an appropriate setting for "I Was Glad", but often Parry's music has been virtually hijacked for purposes that little resembled his original intent, both during his lifetime and since his death.

A biography of Parry by Jeremy Dibble is now on sale on a website devoted to Royal Wedding memorabilia. But here's the quote from the composer on its first page: "The mission of democracy is to convert the false estimate of art as an appanage of luxury." Far from wanting to be an establishment mouthpiece, Parry knew that music was for everyone, regardless of wealth or "class".

How many people singing "Jerusalem" have the first idea of why he composed it? It was actually created for a meeting in 1916 of Fight for the Right, the movement that was trying to win enfranchisement for women and which he and his wife both supported. Later, in the final stages of the suffragettes' campaign, Parry conducted "Jerusalem" himself in their celebratory concert. It's often regarded as the unofficial "national anthem of England" – but if it is anyone's emblematic theme, it is that of feminism. If he knew that BNP supporters would espouse his hymn as a favourite nationalist tub-thumper, Parry would turn in his grave in St Paul's Cathedral.

Since the royal wedding, Parry's name has been bandied about together with the word "genius". Unfortunately, he wasn't one. His music is an endearing mix of mild inspiration, massive aspiration and decent craftsmanship, topped up with hot air. As a composer, he was the ultimate English amateur, though that wasn't entirely his fault. His father, a director of the East India Company, attempted to steer his studies away from music and his aristocratic in-laws tried to prevent him following a career in it. If he had not given in to these very British upper-crust prejudices, but followed his dreams from the beginning, perhaps he could have fulfilled his potential.

Instead, he sacrificed his artistic ambitions for love. Determined to marry the girl on whom he had set his heart, Lady Maude Herbert, he bowed to her mother – who objected on the grounds of Parry's finances – and meekly took a job with Lloyd's as an underwriter. He stayed there throughout his twenties, pursuing music on the side. The opportunity to work on The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians propelled him back in the right direction, along with the mentorship of the pianist Edward Dannreuther, a passionate admirer of Wagner. For Dannreuther, Parry wrote his first well-received piece: the Piano Concerto, full of verve and colour.

In 1887, Parry was hijacked again, this time by his own success: his ode "Blest Pair of Sirens" brought him numerous commissions for a genre of music he didn't much like. His views were humanist and Darwinian rather than churchy. Still, he complied and wrote some oratorios. These had their moments, especially Judith, from which the hymn tune "Repton" is drawn. But George Bernard Shaw dismissed his Job as "the most utter failure ever achieved by a thoroughly respectworthy musician".

Besides these, Parry penned countless church anthems, five symphonies, incidental music for the theatre, chamber music, piano music and some excellent songs. Yet his works have never won a real place in concert life beyond the church – and have little hope of recognition abroad, in countries that pride themselves on more sophisticated musical achievements.

Ultimately, he became best known for his teaching. He was director of the Royal College of Music and in 1900 was appointed professor of music at Oxford University. His crucial influence extended over Elgar, Holst, Howells and Vaughan Williams – the latter also espoused Parry's liberal, humanist attitudes. He was kind, perceptive and popular, as the musicologist Donald Francis Tovey remarked while studying with him at Oxford, writing: "Dr Parry embellishes a pupil's piece of platitudinous ponderosity by extracting the juices of the pupil's brain, and concentrating them into an essence while he mysterious increases the quality!"

There's one more twist in Parry's tale: despite the true-blue Britishness seemingly branded into his music, all the influences upon it were German, notably Brahms, Beethoven and, above all, Wagner. His ceremonial effects and sweeping melodies – the same espoused by Elgar in the Pomp and Circumstance marches – came straight from Wagner, and especially from the overture to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Yet that overture's grandeur is tongue-in-cheek: in this opera (now about to open at Glyndebourne), Wagner pokes fun at the way hidebound traditions hinder the progress of new ideas. The opera's hero, Hans Sachs, extols the superiority of German art. Parry seems to have agreed. On the outbreak of the First World War, he was heartbroken by the conflict between his country and that of the culture he loved. He died in 1918 in the epidemic of Spanish flu.

The spirit of old-fashioned German art permeates Parry's music – just as German roots underpin the British monarchy that is celebrating him now. But here are three cheers for the real Parry: the liberal humanist, the supporter of feminism, and the champion of music for all.

'The Prince and the Composer' is on 27 May at 7.30pm on BBC4

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments