A Midsummer Night's Dream: Not so great Britten

Radical reinterpretations of classic operas are nothing new, but putting paedophilia into A Midsummer Night's Dream is a step too far, says Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is it about opera that drives the most sensible and the most experienced directors to dream up the most outrageous interpretations which, while sometimes brilliant in their own right, have nothing to do with the work or the composer's intentions? This year we've had Faust as a parable for the Jewish holocaust and Simon Boccanegra as view of contemporary Italian politics. Now, to cap it all, we have had Benjamin Britten's Midsummer Night's Dream, not as a reverie but as a recalled memory of paedophilia and child abuse suffered by Puck at the hands of Oberon, the King of the Fairies, represented this time as a schoolteacher.

One gets the point. How could you not when it is made so explicitly, on a stage set in a Victorian schoolyard with the insignia "Boys" over its entrance? Benjamin Britten was gay and, at various times in his life, took up the interests of school boys only to drop them when their voices broke. David Hemmings is the most obvious, and painful, example. It was destructive to the boys and agonising to Britten.

There's little argument, too, that in his operas he expressed some of his concern and fears of sexuality. The Turn of the Screw, Peter Grimes, The Rape of Lucretia all have a troubling sense of abusive relationships. You can, if you like, interpret the fight between Oberon and Tytania, the King and Queen of the Fairies, over possession of a changeling boy in this light. You can certainly see Puck as a morally ambiguous figure and the fairies as far from wholly benign. The text could support all sorts of subliminal feelings by the author.

Except that is not what the music says or Britten intended. Britten wanted to express the ethereal, the ambiguous and the human qualities of Shakespeare's play; the director, Christopher Alden, has decided to make it a dour and depressing journey back into an abused childhood. Michael Boyd of the RSC described it as a production that "really gets to the heart of it". Heart, however, was the one quality entirely lacking. Instead we had a cold, calculated effort to impose a director's view of a composer on a work created to translate Shakespeare's magical play into musical form.

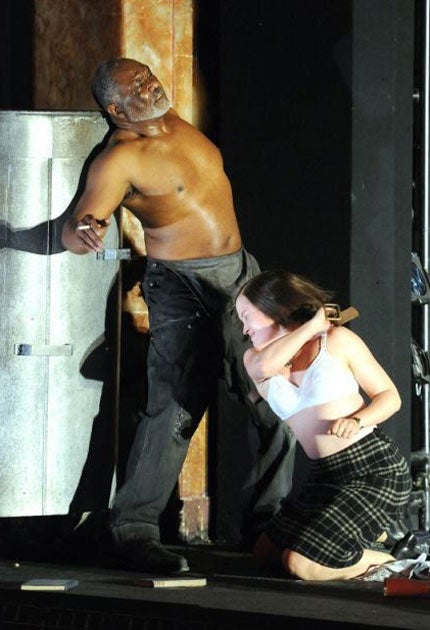

This is not a hoary old argument about re-interpreting opera or theatre using entirely different periods and settings. We've had that debate ever since Peter Peter Hall stormed out of Glyndebourne on seeing a Peter Sellars production of Mozart's Magic Flute that put the action on a California freeway. For years opera directors have played a deliberate game of outraging the traditionalists, usually by introducing sex on the stage (Midsummer Night has an entirely gratuitous scene of Tytania, stripped to the bra, beating the hell out of the adult Puck figure).

Giving operas new texts can seem perverse (it did in the case of Mozart) but it can bring new life to works grown over-familiar in their traditional settings. Two of the most satisfying productions this year were revivals of productions which were roundly criticised at their first showing: Parsifal at the English National Opera and Phyllida Lloyd's Macbeth at the Royal Opera House played to packed and enthusiastic audiences in the cinema. The first ended on a railway track indicating the future of the Holocaust, the latter had the sets dominated by a gilded cage. ENO has done wonderfully well with its series of Janacek operas updated to Soviet times (directed, incidentally, by David and Christopher Alden), as has Covent Garden with Rimsky Korsakov's The Tsar's Bride at the Royal Opera House.

The problem comes not in novelty but in imposing concepts that may do everything for the director's reputation but nothing for the work itself. Reinterpreting artistic creations solely in terms of the personal history of the artist, as Christopher Alden does with Britten's Midsummer Night's Dream, profoundly misunderstands the process of making a work of art. However passionate the artist, however intent on expressing his or her feelings, working with music, theatre or any art involves grappling with form.

Britten's chief concern in doing an operatic version of a play he admired and well understood was to find the musical styles to delineate the different worlds of the fairies, the lovers, the Court and the "rude mechanicals". To meld these into one grim remembrance of schooldays is to deprive the audience of the meaning of some of the composer's most inventive music. To end the opera on the dour note of a marriage made impossible by the past is clever. It may even be moving. But it flattens and twists some of the most sublime finales in music.

Once a work is written, it's public property, of course. For a director to take on an opera and try to refashion it in his own image may be considered arrogant but it is an arrogance that drives performance forward. The problem with productions such as Midsummer Night's Dream is that they are fundamentally self-serving. They impose concepts as a substitute for grappling with, rather than elucidating, the work. For some, the travesty in this production is the way it traduces the character of Britten himself. Britten was a far more complex personality, and a far more self-doubting and moral one, than is suggested by presenting him as a manipulative abuser of young boys.

The real insult, however, is to Britten as an artist, one of the great composers of the last century, and certainly one of the greatest British ones. He knew what he was doing with Midsummer Night's Dream. He loved the different worlds it inhabited, each commenting on the other, and he revelled in the things that made it a comedy, not least the play put on by the rude mechanicals (Bottom is splendidly played by Willard White, a singer who understands exactly what the composer was about). The humour is in the music, the joyous pastiche of Italian opera conventions, as much as in the words.

I don't deny the theatrical effect of this sort of radical re-interpretation. As I came out, the foyer was abuzz with talk of schooldays, beatings (there is one, of course), predatory teachers and just what various bits might mean.

It was the same with Terry Gilliam's version of Berlioz's Damnation of Faust earlier in the season. The production was quite brilliant, turning the story of damnation into a story of the genocide against the Jews. Full of visual invention, the narrative held together with great effect. Berlioz, like Goethe, was not interested primarily in the depths of evil. He was taken with the human story of a man locked away in his books who yearns for the full passion of love and sex and is granted his desires by the Devil – only to betray both himself and the girl he falls in love with. The subject is romantic; the music is deliriously French Romantic; the final moral is about man's weakness and his fall.

When Leonardo painted his portrait "Lady with an Ermine", the centrepiece of this autumn's National Gallery show, he was painting a woman, womankind and the mystery of the person behind the face. He wasn't expressing a deep-held conviction about the treatment of animals or the privilege of wealth. It might be clever to say he was, but it is not illuminating.

Exactly the same is happening with the current vogue for doing plays, and particularly foreign plays, in "new versions". You may get a more striking or more approachable piece of theatre by rewriting the text but you also detract from the work itself. What we are seeing here, as in so much of theatre at present, is a triumph of effect over content. Skilled directors seek to engage the audience with striking effects but not to engage the author, which requires more work and more humility.

Opera productions are particularly prone to this. One of the problems is the medium. Opera, by its nature, has something over-the-top about it: its plots are seldom realistic or its characters sober-minded. Another problem is the money. Opera has bigger production budgets than straight theatre. And the productions attract far more publicity for the interpretation, and the more radical the better. Directors hungry for fame see the major opera houses as a platform for their ambition. Damn the music and the composer, just take the plot and make it into something people will talk about. All that's needed is the money and the support of the publicity directors.

The answer is to deprive them of both. With the axe falling on the arts, why not simply hand directors a CD of the music along with the libretto, a copy of Peter Brook's The Empty Space, a limited budget and see what they make of it? Then we might get some really searching productions that bring the works of great composers to new life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments