Channel 4, the champion of yoof: how the revolution was televised

If the broadcaster is to be part-privatised, will it lose its edge? Mike Bolland, the channel’s first youth controller, recalls how an ‘alternative’ public remit led to blowjobs at teatime, ‘fuck’ counts, sacrilegious cigar commercials and scandal-hit ministers (nearly) unmasked: no wonder Mary Whitehouse wasn’t a fan

I arrived at Channel 4 in October 1981 with a brief to commission programmes for a young adult audience. In the first weeks, we created weekly evening sessions where young people met up with sympathetic producers in order to thrash out what this television should be. After several meetings it was clear that music and comedy were top of the agenda. There was a strong feeling that young adults couldn’t see people like themselves or any of their interests reflected on television. We had a strategy.

The first pitch came from “alternative” comedian Peter Richardson. He proposed a series of films featuring the cream of the new-wave comics. The satirical films would be parodies of different genres. He got particularly animated when describing The Comic Strip Presents...Five Go Mad In Dorset. The wicked lampoon of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five adventures was already well formed in his mind. It challenged class, racism and sexism from an entirely different angle. It was a no-brainer. The new comedians had been hard to televise. They didn’t lend themselves to conventional coverage. Peter offered an accessible way of getting those radical performers on air.

Then came Andrea Wonfor from Tyne-Tees Television. She offered Jamming – six half-hours of music. I really liked Andrea and her producer Malcolm Gerrie. I greatly admired the shows they made for ITV, but Jamming didn’t excite me. I had this huge tranche of airtime to fill on Friday and I was quietly concerned that live television didn’t seem to be on anyone else’s shopping list. I put the idea of a six-month run of a live music show with attitude to Andrea and Malcolm.

At first I don’t think they believed that I was serious, but when the penny dropped they went for it with incredible enthusiasm and inspirational creativity. The Tube was to be energetic, irreverent and funny. The music was live and relevant and the comedians ranged from weird local Foffo Spearjig The Hard through French and Saunders to Dame Edna Everage. The early slot was problematic, and at times brought us many slapped wrists from Ofcom’s ancestor, the Independent Broadcasting Authority. We regularly appeared on Right to Reply. Apparently, any mention of blowjobs at teatime is taboo. Who knew? Nowadays French & Saunders are national treasures.

In the summer of 1982 we filmed Five Go Mad in Dorset. News that Channel 4 had commissioned the show reached the BBC and – surprise, surprise – they exercised the option they had taken on The Young Ones. With the bulk of the cast gone to the BBC we had to postpone filming after Five Go Mad. We only had one episode of The Comic Strip Presents... available and Jeremy Isaacs scheduled it for the opening night. The day before the launch my phone rang.

The call was from solicitors representing Enid Blyton’s estate. They had read about our show and were threatening an injunction. It was agreed that lawyers for both the estate and the publishers could view the film later that day. The viewing took place in my tiny office at Charlotte Street. We squeezed two barristers, two solicitors, Enid Blyton’s niece and the man from Hodder & Stoughton into the room and switched on the VCR. With C4 colleagues I stood outside, watching through the glass wall. One by one, the lawyers were covering their faces with their papers in order to hide unseemly mirth.

We got to the night scene of a tent into which Timmy the dog had his head and front quarters. His rear end was sticking out and his tail was wagging vigorously. The immortal line from Dawn French, “Oh Timmy, you’re so licky”, heralded the end of any composure. One of the solicitors couldn’t hold it in anymore and she loudly guffawed. The tears were running down her face and that relaxed the others. Soon my wee room was full of laughing lawyers. The man from H&S also laughed. The lady from the Blyton estate didn’t. Mr H&S gently chided me as they left. He thought that we had pushed our luck but that it was really funny. The show went out to a mixed reception, seriously splitting the audience down the middle. That felt to me like a result – as did the fact that I didn’t get fired on Channel 4’s first day of transmission.

For some reason, the IBA had a stricter code on language for comedy and entertainment than it had for documentary or drama. There was constant dialogue between us about whether or not certain swearwords were funny and/or acceptable. It was like a war of attrition, an amiable war but a long war nonetheless. We’d argue the “fuck” count for Comic Strip on a regular basis and slowly but surely the barriers came down. Part of the problem was that the style and rhythm of the comedy was alien to many (older) people who viewed it.

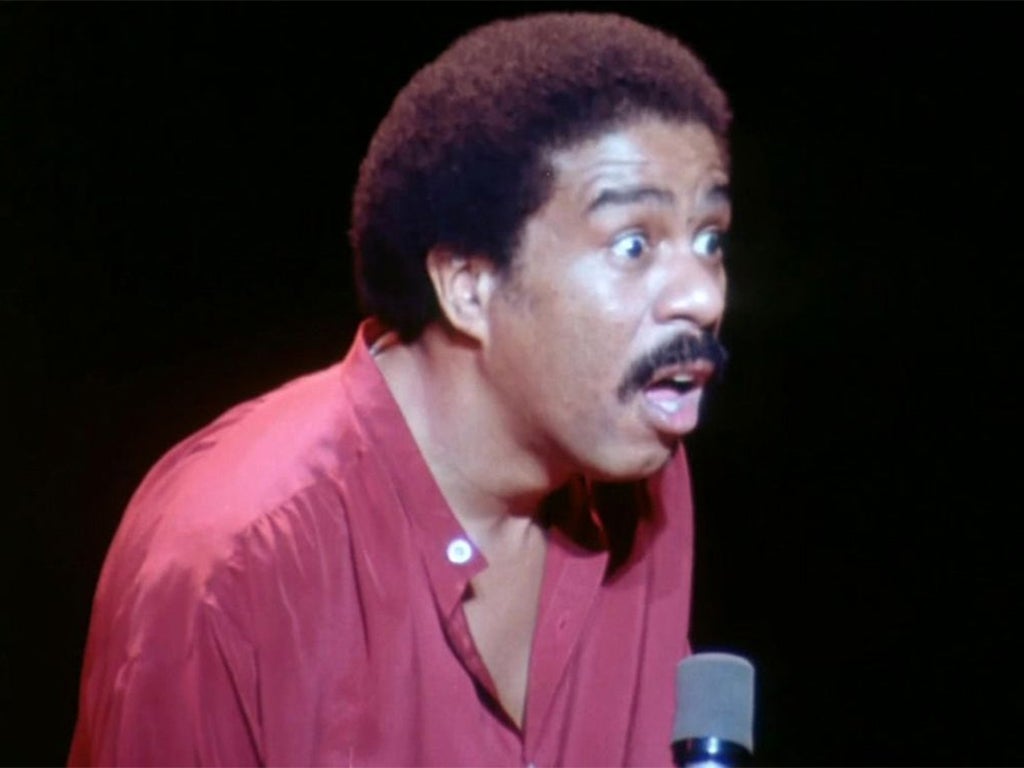

Often we were arguing from completely different standpoints with little or no common cultural reference points. Jeremy Isaacs persuaded the watchdog to allow a screening of Richard Pryor: Live in Concert. Technically it was a documentary but in essence it was a record of a performance – a comedy performance. The “fuck” count was high and the Channel 4 audience was introduced to those words and much worse. It was a big psychological leg-up for my side of the argument. Sadly the battle to screen Monty Python’s Life of Brian hadn’t at this point been won. Crucifixions were not yet the stuff of comedy.

Then came Who Dares Wins, made by the team that later morphed into Hat Trick Productions. The comedy was in part satirical, at times observational and always bitingly funny. The offending sketch was a dig at the advertising industry. It had no dialogue and satirised the old cigar advertisements in which any desperate situation could be fixed by puffing on a Hamlet. The crucifixion scene was beautifully shot. It resembled a religious renaissance painting. Choral music played as a cigar was given to Jesus. He was unable to get a light from a flame, which was on a long stick tantalisingly just out of reach. He wrenched his hands away from the cross in order to bring it nearer. He lit his cigar. The music changed to "Air on a G String". He fell out of frame. Sacrilegious but funny.

There followed, unsurprisingly, many difficult exchanges with the IBA, Mary Whitehouse muttering about criminal blasphemy, and a toe-curling appearance on Right to Reply. Many viewers wrote in support of our standing up to previously unassailable institutional taboos. Many were less supportive. My favourite letter vividly described in detail the horrors of an eternity of brutal bestial torture in hell. It came from a church minister in Scotland.

We were now no longer permitted to transmit live. We recorded on Friday night for a Saturday evening transmission. After each recording a VHS copy of the show was sent to Channel 4 controller Paul Bonner. The producers and I met on Saturday mornings to edit the show taking into account Paul’s notes.

What could possibly go wrong? The new system worked for a while until the production team got a tip-off that news and current affairs bosses were being warned off any mention of alleged sexual shenanigans involving a very senior member of Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet. This was the era of the D-notice – an official request to editors not to publish or broadcast certain items because of national security. But we were lowly entertainment beings, therefore not party to any news briefings. A sketch was performed in which Jimmy Mulville interrupted an interview in front of the audience. Something bad had happened, he said and, in a handheld camera shot, we all left the studio and tracked through the reception area into the gents’ lavatory. Above the urinals there was graffiti. It read: “The Cabinet Minister involved in the sex scandal is…” and then the first two letters of his name, with the rest scribbled out. Who on earth could it be?

Next morning, we started the edit fully expecting a phone call with instructions to remove the offending item. It never came. The sketch was transmitted. There were understandably demands for heads to roll. As ever, Jeremy Isaacs was a pillar of strength throughout and, although he was unhappy with our actions, gave us his full support. There was to be no Right to Reply appearance this time. There was no public outcry. It all went very quiet. With hindsight, it’s easy to see why.

The channel then installed an experienced current affairs executive producer, John Gau. He was a lovely man who was never quite sure why he was there but seemed to enjoy every minute of it. We continued to upset people – only now with John’s blessing. Importantly, Who Dares Wins was a very funny show that stretched boundaries and found a hitherto unengaged audience.

Who Dares Wins was my last commission as youth editor before moving to look after entertainment overall. My change of role was scheduled to happen the week after the crucifixion debacle so it felt good to be employed, let alone promoted.

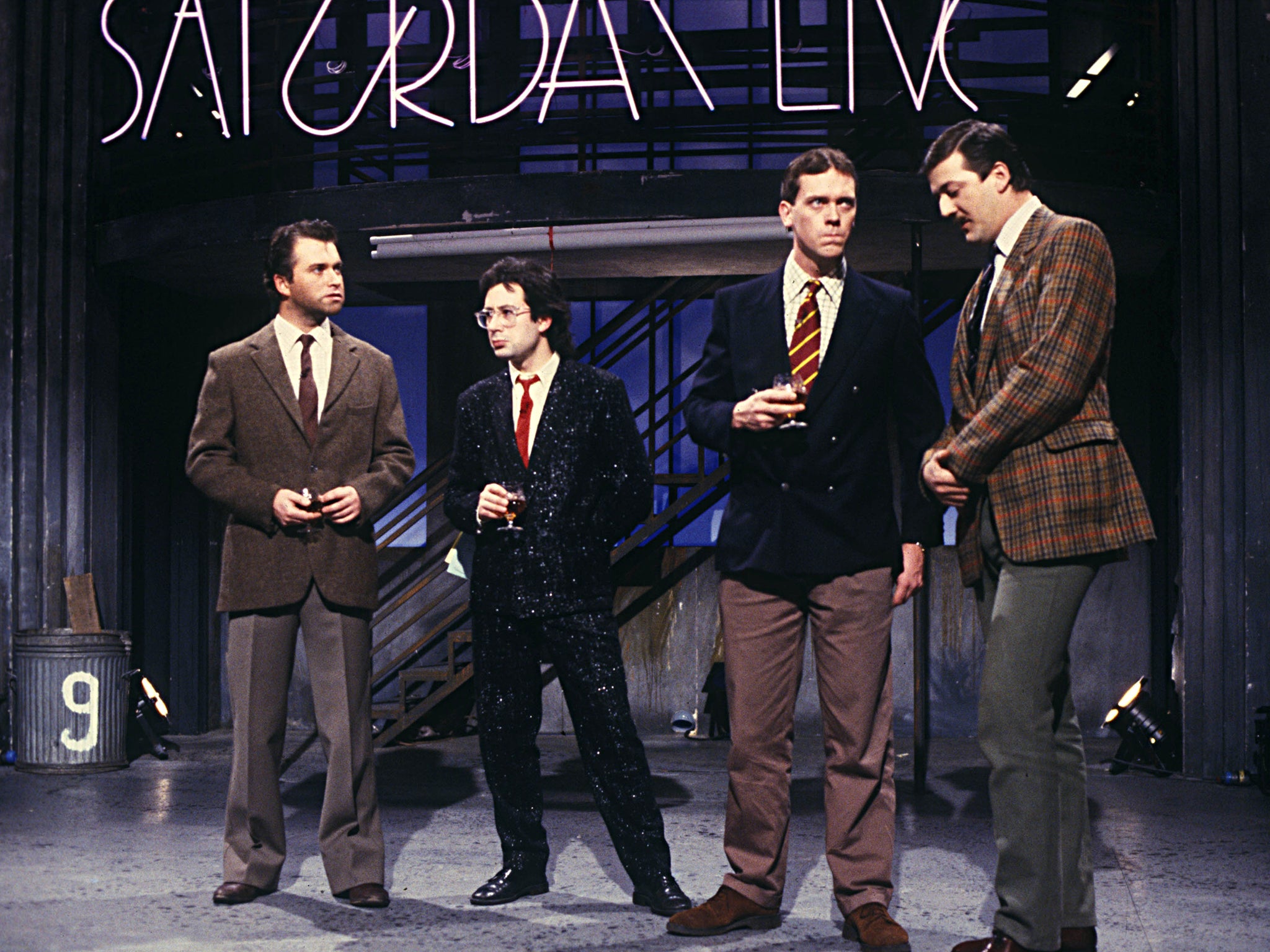

My new job was to give me the opportunity to realise a major ambition. Saturday entertainment has always been a challenge for television channels. The Tube started the weekend in fine style for the young audience but where were the shows for the slightly older viewers – the young at heart? The plan was to create a variety show for the Eighties. Producer Paul Jackson and I had discussed this for a long time and our starting point was a sort of Tube in reverse – a live show driven by new comedy. There would be music but on Saturday Live comedy was king.

With the weight and experience of London Weekend Television production behind us, we went on air in 1985. The first series had a different guest presenter each week and introduced all sorts of new faces to television. It made stars of Ben Elton and Harry Enfield. It introduced us to Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie. Channel 4 favourites Rik Mayall and Ade Edmondson brought us the Dangerous Brothers, a genuinely funny take on slapstick – with added genuine danger.

The second series was fronted by Ben and Harry, the latter creating the characters Stavros and Loadsamoney. By the time we moved to Friday, Ben and Harry were well established and Loadsamoney had become the iconic symbol of Thatcher’s Britain. Amongst the new faces in those series were Paul Merton, Julian Clary, Jo Brand and Lee Evans as well as Bing Hitler, aka Craig Ferguson.

Saturday Live and Friday Night Live had a pre-watershed transmission. This meant that it had to be tightly scripted and LWT had lawyers all over it. In many ways it epitomised the tension that sometimes arose between the big ITV companies and Channel 4. Editorial responsibility rested with Channel 4 as publisher. In truth, the companies didn’t really get that, and always had one eye on their own franchise renewal. By the third series I was conscious of LWT regarding the show as their property. Paul Jackson was no longer there so the team had changed, as had the dynamic. It didn’t have any effect on the show. It was in the creative hands of the Geoffreys Perkins and Posner so all was well, but by now it had done its job. It was time to call it a day. Quit while you are ahead.

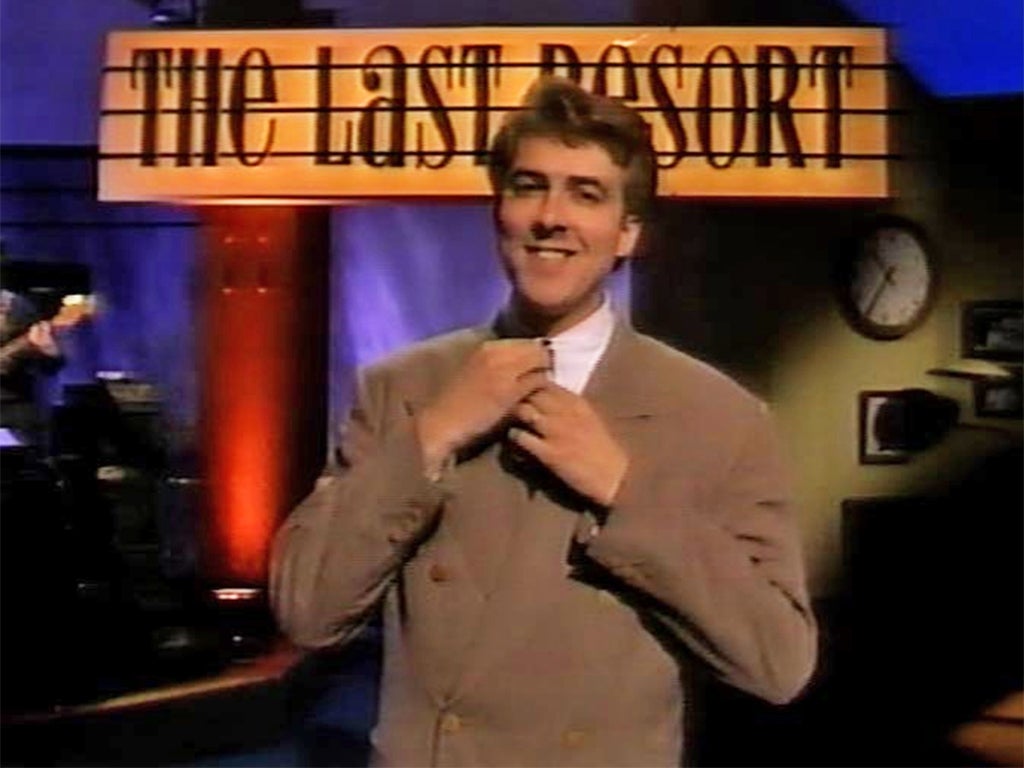

In 1986 two young researchers came up with the next big thing. They were working on the music show Soul Train, produced by (my wife) Katie Lander. One of them was Alan Marke, who had been one of the young people on the 1981 “think-tank”, and had given up working in local government to pursue a career in television. The other was Jonathan Ross. Together they proposed making a British version of the US talk show The David Letterman Show. It was a great idea. The only problem was that in order to make The David Letterman Show you need a David Letterman.

We were going to make a pilot so we would have to find a host. Alan, Jonathan and I spent a lot of time searching for the elusive talent. We auditioned in London and at the Edinburgh Festival. We drew a blank. Over the course of this search Jonathan would brief the candidates and demonstrate what style was required. It soon became obvious that he was far better suited to the role than any of the hopefuls we had seen. I asked him if he would do it. He said yes.

We made the pilot. I thought that Jonathan was great but the show didn’t work. We had to find a new producer. I showed the tape to several noted names. None of them got it, nor could they see what I saw in Jonathan. The words “speech impediment” came up more than once. The one person who shared my confidence was Colin Callender. Colin had produced the acclaimed Nicholas Nickelby early in Channel 4’s life. The Callender Company would make the show.

Colin brought Katie in to produce it as she had experience both of studio shows and of working with Jonathan Ross. The first show went out very late on 6 February 1987. We pre-recorded it at 5pm and, from the minute we finished that first recording, we all knew that we had something very special. It felt different to any other chat show. It felt fresh. It felt right. The pre-recording and the transmission time felt wrong. It should be live and it should be earlier.

In those days at Channel 4, new challenges could be met with brave resolve. Jeremy Isaacs listened to my case for a live show and asked what my preferred slot would be. I said that the show would play well at 10.30pm. From day one, this slot had been a sort of “disease of the week” slot. Putting an irreverent chat show in there would fundamentally change Channel 4 on a Friday night. Quite.

We got the green light to go live as soon as possible allowing for print TV listings to be in sync. It took less than four weeks until The Last Resort settled into its new live slot. It proved to be a huge hit for Channel 4.

The next big challenge was improvised comedy. Improv had been tried on earlier shows but had failed. Hat Trick pointed out that there was a great new show on Radio 4 that would work really well on television. Whose Line is it Anyway? was made by a bright young producer named Dan Patterson, who had devised a format that enabled improv to work, to be believable and funny.

When the BBC found out that we were interested, Dan ended up in the middle of a bidding war. Controller of BBC2 Alan Yentob personally took on the job of winning the show so poor old Dan was getting frantic phone calls yanking him in every direction. I’m sure that Hat Trick’s involvement helped win the day for Channel 4 and I honestly believe he made the correct choice. It was the right home for the show. It proved to be another huge hit and ran for 10 years on the channel. Dan’s company still makes the show in the US.

At the end of the Eighties there were many changes at Channel 4, not least the departure of Jeremy Isaacs and the arrival of Michael Grade. I ended up as controller of arts and entertainment and deputy director of programmes. It wasn’t as grand as it sounds. I didn’t do much deputising and I didn’t have a programme budget. Jonathan Ross and Alan Marke had found an exciting new act and were seeking a commission. The problem was that none of the commissioning editors wanted to spend any of their budgets on the idea. There was, however, a contingency budget to be won and Michael Grade was the man to convince. Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer were performing their show live at the Albany theatre in Deptford in south-east London. We took Michael to see the show or rather he took us in his chauffeur-driven car – lots of us all squashed in. He got it right away. Vic Reeves Big Night Out owed much to the Goons and Monty Python, but it also had its roots in music hall. The surreal comedians had excellent catchphrases. Michael could be heard proclaiming “he wouldn’t let it lie” for many weeks after the performance. The show was commissioned and Big Night Out launched the career of those unique performers whilst pioneering a type of comedy that has inspired many new acts since.

I left Channel 4 in 1990, just as newsroom sitcom Drop the Dead Donkey was starting. A character in Who Dares Wins called Damien inspired the series. It was a narrative comedy whose only home could be Channel 4. Its directorial style, its subject matter, its topicality and great characters gave it a distinctive feel. Following this success entertainment commissioning editor Seamus Cassidy went on to have the biggest hit of all – Father Ted – one of the great British sitcoms of all time. Both shows were produced by Hat Trick.

Over the years Channel 4 has continued to offer fresh takes on comedy. Titles such as Peep Show, Black Books, The IT Crowd, Smack the Pony and The Inbetweeners have kept the comedy flag flying. Many new comedy writers and performers have made their debuts on Channel 4. BBC3 has inexplicably been “demoted” to an online presence, making it vitally important that Channel 4 carries on with the innovative work. Peep Show and Fresh Meat are coming to an end, but shows such as Catastrophe and Raised by Wolves are still being commissioned.

Comedy has flourished on 4. Brass Eye, Ali G, Green Wing, Peter Kay, Armstrong and Miller, Absolutely, Paul Merton, Friday Night Dinner, Mark Thomas, Bo’ Selecta!, Adam Hills, Paul Calf/Steve Coogan, Spaced, Jack Dee, So Graham Norton, Clive Anderson, Desmond’s, Keith Allen and Black Books – a list spanning more than three decades and, inevitably, I’ve left out lots of great names. The point is that Channel 4 takes the initiative to air new talent. The angry young things from the channel’s early days are now amongst the good and great of broadcasting across all networks. Indeed, they probably now represent the very generation that they railed against in the past. Is it time for a new wave of performers to challenge them? I think it is and I believe that Channel 4 should encourage and support them. Its current constitution certainly makes it the natural home for new voices. Nobody else is going do it.

This is an edited extract from ‘What Price Channel 4?’ (Abramis, £19.95), a collection of essays edited by John Mair, Fiona Chesterton, David Lloyd, Ian Reeves and Richard Tait

The book is published on 7 June, but is now available to Independent readers at a special price of £15. Email richard@arimapublishing.co.uk for details, putting ‘Independent offer’ in the subject field. To be published on 7 June, the book is now available to Independent readers at a special price of £15. Email richard@arimapublishing.co.uk for details, putting ‘Independent offer’ in the subject field

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks