Britain is right to celebrate the abolition of slavery, but must acknowledge excesses of empire

As the UK celebrates its role in the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, it’s important to recognise that Britain’s humanitarianism was ultimately cut from the same cloth as imperial expansion

Britain’s Anti-Slavery Day should remind us that – despite the country’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807 – the global trafficking and enslavement of people is still very much with us. When the country celebrated the bicentenary of its abolition of the slave trade in 2007 the government explicitly linked the celebration with reminders of the continuing problem of slavery and human trafficking.

But for most people in Britain it was seen as an occasion to celebrate the fact that Britain – then the world’s most powerful country – had played the leading part in rendering slavery unacceptable across the world. The dominant narrative was that of a benevolent empire leading the globe in the establishment of humanitarian principles.

And, while aspects of this narrative are true, 19th century British policy also laid the foundations for the more troubling aspects of our modern humanitarian scene – an often patronising endeavour to meddle with the customs and belief of others, to make “them” more like “us”.

When you take a closer look, Britain’s humanitarianism was part of the very fabric of imperial expansion – and reflected all its ambivalence.

Spreading the message

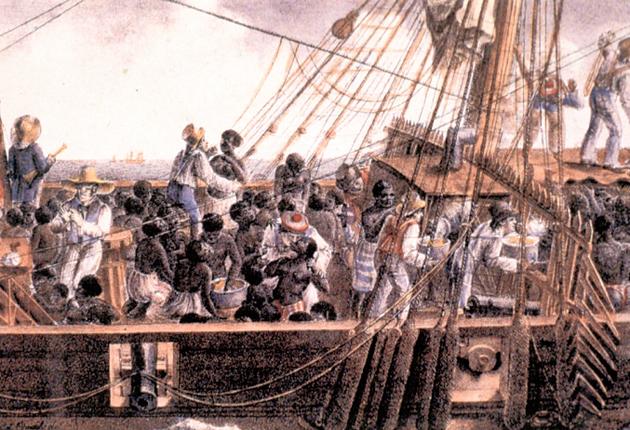

Britain’s anti-slavery campaigns enlisted activists who were encouraged to feel responsible for the plight of enslaved strangers in distant countries. These enslaved people were almost always depicted as helpless, passive and in need of help from more “advanced” Westerners.

These developments have been claimed by historians of both humanitarianism and human rights as a foundational moment – and yet this was far from a rights-based project and it was far from globally projected. The word “rights”, as in Tom Paine’s “Rights of Man”, in which individuals are entitled to rebel against governments which do not respect their natural rights, was anathema, both to British imperial officials and to most anti-slavery campaigners throughout this period.

These were rights that had been associated with revolutions in France and America and which Britain’s imperial officials – who were mainly drawn from the military – had directly fought against. More fundamentally the expression of these rights implied a rejection of the crown and the church as the foundations of the state.

When revolutionary sympathisers spoke of the Rights of Man, British officials saw only the threats to individual liberty promised by the rule of the revolutionary mob. Evangelicals saw only a tendency towards atheism. So while it was seen as humanitarian to resist the actual enslavement of people, the idea that those people were entitled to “human rights” which classed them as fully functioning agents of their own destiny with all that this implies had yet to gel.

Emancipation and dispossession

After the abolition of the slave trade, those already enslaved remained in that state until 1833 and were even then subjected to a further four years of “apprenticeship” to their former owners. As apprentices they were subject to new policies of amelioration intended to prepare them for freedom. These policies restricted the hours they could be made to work and the punishments that “masters” could inflict upon them, but still bound them to work for their former “owners”. At the same time, policies of “protection” marked the globalisation of Britain’s humanitarian government, appointing officials whose job was specifically to look after Indigenous peoples in the empire.

This was because the transition from slavery, via apprenticeship, to emancipation in the Caribbean coincided with the mass emigration of British settlers to dispossess the Indigenous peoples in North America, Australasia and southern Africa. The same reformers who had mobilised against slavery now turned their attention to the plight of Indigenous peoples who were being dispossessed in this era of colonisation.

Protectors of Aborigines (modelled on the protectors of slaves) were sent to Australian colonies and New Zealand and officials elsewhere were instructed to protect the lives and preserve what was left of the landholdings of Indigenous peoples. On these landholdings (reserves, mission stations, protectorate stations) peoples whose lands were being invaded by Britons were allowed to maintain some of their own customs and practises until such time as they were ready – like the apprentices of the Caribbean – to be subjected to the same laws as the settlers around them.

During this moment of protection, the settler colonies of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa became just as important as the Caribbean had been beforehand in establishing the principles underpinning modern humanitarianism. With policies for the protection of individual Indigenous peoples from harm at the hands of settlers – and the assignment of magisterial powers to protectors of Aborigines, so that they could, in theory at least, prosecute murderous settlers – we might even discern the origin of an early “human rights” principle.

But very few settlers were ever convicted by the protectors – and accompanying the protective impulse was a “civilising mission” that would in time lead to invidious policies such as taking Indigenous and so-called “half-caste” children away from their parents and subjecting Indigenous peoples to the neglect and abuse of the residential schooling system in Australia and Canada.

The principle of protection failed to protect indigenous peoples from British invasion, demographic decimation and dispossession – just as freed slaves in the Caribbean found it largely impossible to compete in a free market without land or capital.

Indigenous people at the receiving end of protection nevertheless used this form of humanitarian governance, despite all its limitations and flaws, to retain control of significant sites as reserves, to become farmers competing in settler economies, and to articulate a critique of settler colonialism in each of the settler colonies. Former apprentices and their descendants in the Caribbean similarly used humanitarian language to defend newly articulated rights.

British prime minister, Theresa May, was right to identify Britain’s pioneering role in ending the transatlantic slave trade, when she recently spoke about William Wilberforce in Westminster Abbey. But we should also remember the stories of those who have actually experienced and resisted enslavement – the Indigenous peoples from the outposts of empire, whose worlds were turned upside down and whose ways of life were had to be reconstructed as recipients of British imperial “humanitarianism”.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com). Alan Lester is a professor of historical geography, at the University of Sussex

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks