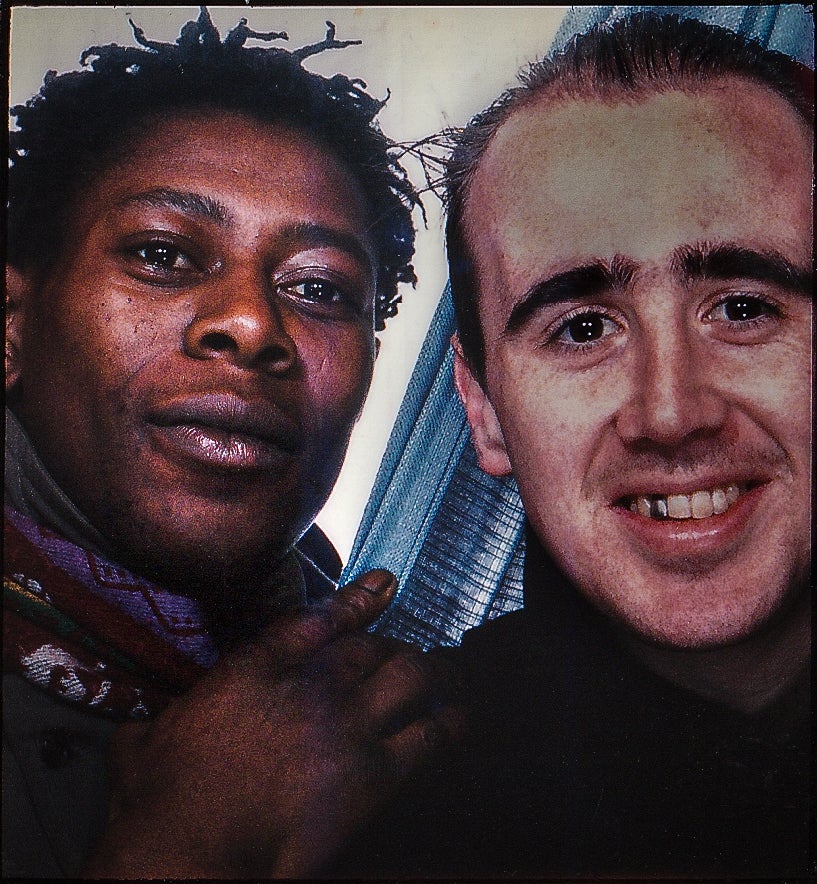

‘We went through 30 years together - making a film about my friend dying became a celebration of his life’

It was a friendship that had spanned addiction and cancer. Leo Regan, the photographer and filmmaker, explains what an extraordinarily special relationship he had with Lanre Fehintola and why they decided to capture his last days

I didn’t set out to make a film about my close friend dying, although that’s what happened. But that’s not what the film, My Friend Lanre, is really about. It’s a celebration of an extraordinary life. An open and honest account, with all its flaws and imperfections, embracing the glorious murkiness of what it means to be alive. And what it means to be a friend.

Lanre Fehintola was an artist and an incredible photographer. He died a couple of years ago, aged 63. During his remarkable life, he was also involved in crime, drug dealing, addiction and had been to prison. For some, these experiences negate or detract from his artistic legacy. For me, the opposite is true. Every wayward sidestep, however unwelcome, brought him closer to his realisation of a life-long obsession; to capture the beauty and humanity of the marginalised and misunderstood.

The results of which, I believe, we all benefit from, as painful as some of those experiences were.

Lanre and I met over 30 years ago at the London College of Printing studying photojournalism. I was in my early twenties and came from Dublin. Lanre was five years older and had moved to London from Bradford.

We bonded pretty quickly, two hungry and idealistic photographers running around with our cameras wanting to change the world. We were obsessed with the idea of immersive photography, idolising photographers like Robert Capa, Don McCullin and Nan Goldin.

Capa was known for his famous saying: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Our lecturers dismissed this as simplistic and naive. We took it as gospel. Chasing the story was the passion that drove us. Lanre, however, would take it to another level.

Documenting the experience was never enough – Lanre wanted to live it. For him, it wasn’t authentic until it was authentic. While he was working on a project about the homeless in London he became so immersed in the work that he ran out of money, got kicked out of his flat and became homeless himself.

He moved back to his home town of Bradford where some of his old friends were involved in the drugs trade. Heroin and crack cocaine were a huge problem at the time and Lanre wanted to document it from the inside.

He followed his dealer friends, photographing and interviewing them, but it didn’t produce the results he desired. He told me that he felt like an outsider, outside the story. For him, the only way to truly understand the life of a drug dealer was to become one, so he started selling drugs.

“I saw the dealing as research,” he told me. “I know it might sound, you know, yeah right, but I didn’t really see myself as a dealer. I just thought I was getting close, you know, close to the story. That’s the whole thing. Get into the story. Become the story.”

I respected Lanre’s decision, even though it wasn’t something I would have done. We were militant about our commitment to photography and storytelling even though our approaches were different. At that time I was following a gang of neo-Nazi skinheads around the county. That was challenging enough for me, I never felt the urge to become one.

Lanre decided to expand his project to include drug users and started photographing a group of heroin addicts, eventually moving in with them. I was alarmed but not surprised when he told me he was using heroin. “It’s the only way I can find out what addiction feels like,” he said. Lanre believed his photography would protect him, keep him focused and pull him through. I watched as it pulled him under.

I visited him every couple of months to discuss the work and keep him energised, but I could see he was completely consumed by his addiction. One of his friends told me that his cameras ended up in the pawn shop. Lanre was deeply ashamed. He’d become a character in his own story.

We’ll continue to the very end. And the people who see it, whatever happens to it, can read whatever they want into it. It will become something, whatever it becomes to them

We hatched a plan to make a film about his experience. The idea was that the structure and demands of filmmaking would keep him focused on getting clean and completing his project. It took a couple of years, but to our amazement, the plan worked. Our film Don’t Get High On Your Own Supply was broadcast on Channel 4 in 1998.

It was a brave and audacious move to expose himself publicly in this way. Typical of the man. His fearless dedication to documenting his decline was remarkable to witness, portraying an honesty, humour and integrity that was, and still is, powerful, devastating and inspiring.

Lanre finally got clean in rehab and his book Charlie Says was published in 2001. The tiny publishing budget didn’t stretch to include his photography or publicity. He was heartbroken. He came out of rehab homeless and broke, turning back to drug dealing and ending up in prison. I tracked him down and wrote him a bunch of letters but it was months before he responded: “I should’ve replied sooner,” he wrote. “But in truth I was surprised you found me. I was hoping nobody would.”

We kept in touch over the years, meeting up to compare notes about whatever project we were working on, our commitment to the work unwavering. I was making documentaries and Lanre continued with his photography.

Three years ago we started working on our new film, My Friend Lanre. He was photographing a group of people living off-grid in a woodland near Taunton. He’d spent five years working on the project and wasn’t sure what to do with it. Lanre had also been diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer. He’d just turned 60. Our plan was to document his cancer treatment and recovery while he finished his project.

You know what they say about plans.

Lanre never made it back to the woodland. He had completed an intensive course of chemotherapy and radiotherapy and his results were looking good. He was doing really well, until he wasn’t. Twelve months after his diagnosis Lanre’s consultant told him she could do nothing more for him. We talked about whether we should continue filming. For Lanre, there was never any doubt. I felt the same way, but it was his decision.

“What we’re doing,” he said. “We’ll do it to the end. We’ll continue to the very end. And the people who see it, whatever happens to it, people can read whatever they want to into it. It will become something, whatever it becomes to them. I see it as an opportunity. It gives it more life, more growth. People add their bits to it and that grows it all the more. That, to me, is wonderful. That’s a beautiful thing. What more can we want in life than if we are born and have that in life? That, to me, is wonderful.”

It’s a huge honour and privilege to be invited to film someone’s private, inner world, especially when they’re at their most vulnerable. It comes with massive responsibility. You find yourself in deeply uncomfortable, tricky situations and it’s tempting to detach and “hide” behind the camera, concentrating on the craft.

But it’s really important to remain present, be there emotionally, however unsettling. If it’s overwhelming, then it’s overwhelming. If that means you screw up the shot or say the wrong thing, then that’s part of the narrative. Life is messy, so is death.

There were many intense and difficult moments while I was filming Lanre’s final months but this isn’t a solemn story. It’s remarkably upbeat and at times, very funny. When Lanre told me that his lung cancer had spread to his brain and he was given months to live, I was deeply shocked. Lanre, on the other hand, was weirdly optimistic, acting like we were discussing a new story idea.

He told me, eyes alight with wonder, tapping the side of his head: “I thought I’d beaten it but the little f***er was sneaking around the back, going into my lymph nodes, through my bloodstream, into my brain… I’m sure scientists see tumours as beautiful, like fungi, fungus, as a beautiful, wonderful thing. If it wasn’t affecting me, I’d probably see it as a wonderful, beautiful thing. But right now you can be beautiful somewhere else. Because your beauty is killing me mate.”

The filming process gave Lanre the ability to have another perspective on what was happening to him. He was able to experience the experience outside the experience. He could explore and examine his plight with his customary fearlessness, curiosity and humour.

Lanre died three months later. He was a unique and exceptional artist who never got the recognition his talent deserved. His life was his art and his art was his life. It’s what I adored about him. Photography was the enduring love of his life and his mesmerising images are woven throughout our film, holding and guiding us as we immerse ourselves in his bewildering journey – just as it held and guided him.

Lanre wasn’t just an amazing artist and photographer, he was an amazing friend, collaborator and confidant. I miss him dearly, but am delighted to report that his spirit lives on in this film.

‘My Friend Lanre’ is released by Emu Films and is available to watch on demand via Curzon Home Cinema until 31 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks