How Bruce Springsteen saved a Pakistani teenager from the Luton suburbs

Sarfraz Manzoor was inspired by The Boss’s rock’n’roll fire, which echoed the angst he felt as a youth in his Eighties home town

Being a teenager in Luton in the 1980s was gruesome enough without the added complication of Pakistani parents who functioned as an in-house anti-fun squad. But for Sarfraz Manzoor, salvation came when he was 16, in the prosaic location of his school common room.

The year was 1987. The sounds of Debbie Gibson, Duran Duran and the Pet Shop Boys wafted from the radio, ear candy to a generation of voluminous-pantsed youths. To Manzoor, these provided little relief from the agony of his particular disaffection. But one day, a classmate lent him a cassette tape of the music of Bruce Springsteen.

“I was like, ‘Isn’t he the guy who makes millions out of pretending to be working class?’” Manzoor says. His classmate responded: “Bruce Springsteen is the direct line to all that is true and meaningful in the world.”

The first song Manzoor listened to was a live recording of “The River”, with its striking, incantation-like spoken introduction. He had never heard anything like it.

“It wasn’t music about escapism but about confrontation – confronting what it’s like to grow up in a town that has problems, to have issues with your parents,” he says.

Unable to afford to buy the records, he went to the library. “I was borrowing the albums and photocopying the lyrics and studying them. I would come home from school and go upstairs and put on Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town and play it all night.”

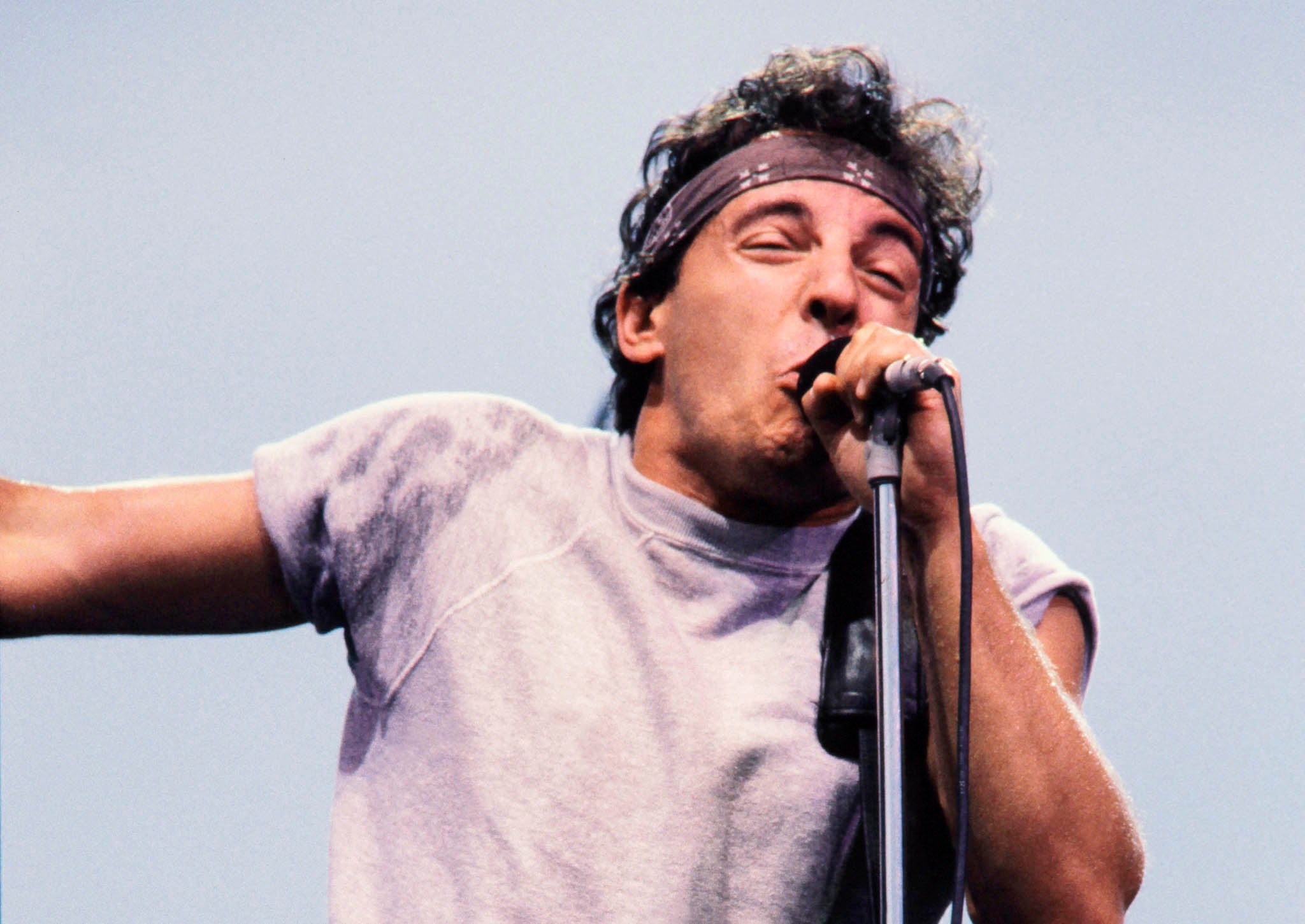

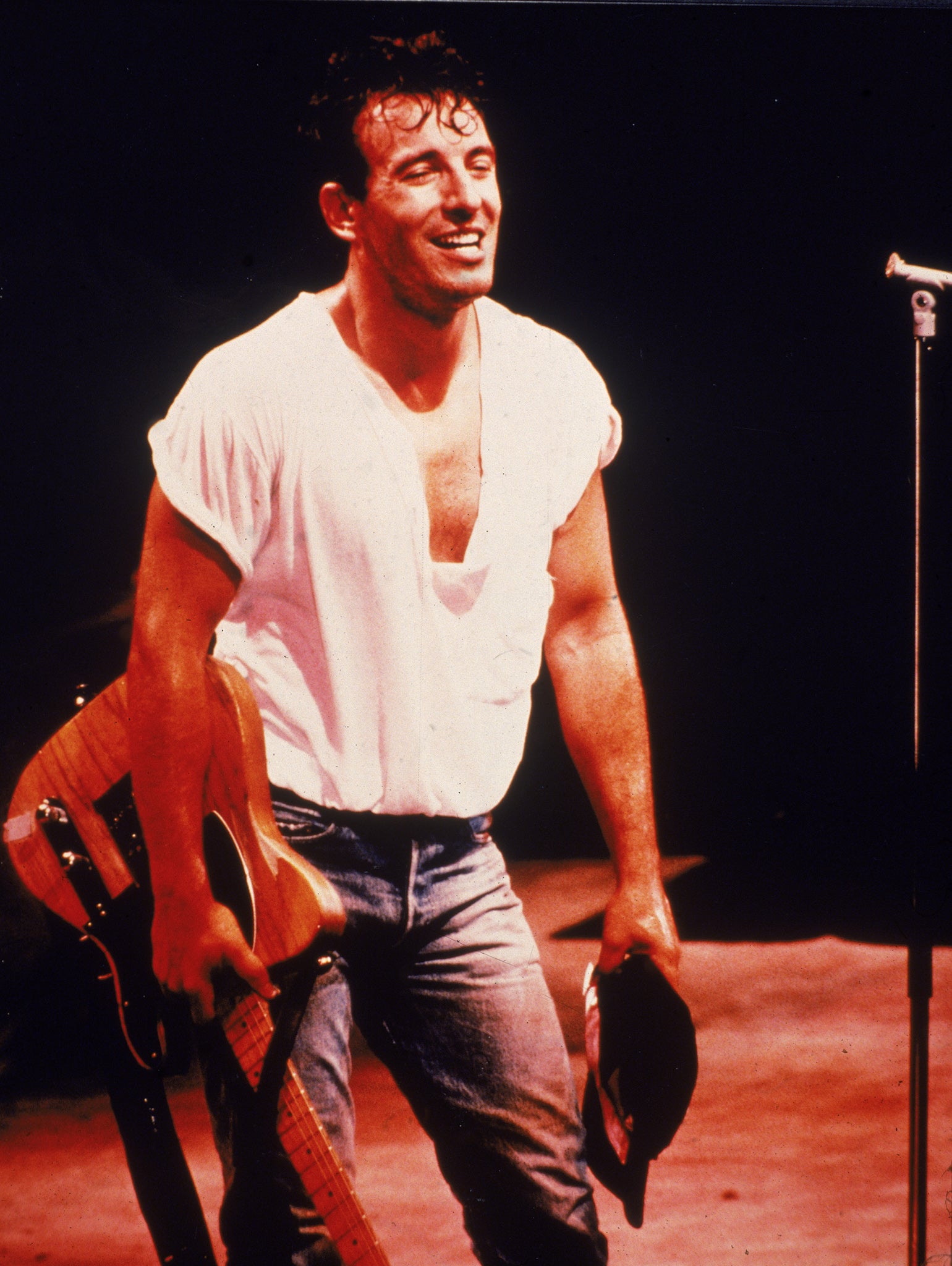

How a bandanna-clad musician from New Jersey helped a Pakistani kid in suburban England survive high school by speaking directly to his troubles – restlessness, alienation, the burden of parental expectation, inchoate longing, being working class, being poor – was the subject of Manzoor’s 2007 memoir, Greetings From Bury Park: Race, Religion and Rock ’n’ Roll. It is also the subject of the recently released film Blinded by the Light.

(Bury Park is the name of the Luton neighbourhood where Manzoor was born. Alert Springsteen-ophiles will notice that the book’s title echoes that of Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ)

Directed by Gurinder Chadha, the movie has a similar feel-good multicultural-triumph-over-adversity vibe as her best-known movie, Bend It Like Beckham.

After Yesterday, Danny Boyle’s fantasy about a suddenly Beatles-free world, it is the second major movie released this year featuring a nonwhite Briton whose life is changed by the transcendence of music.

Manzoor is now 48, a seasoned journalist and the father of two children with his Scottish wife, Bridget. He is working on a new book and often does his writing at the British National Library, where he sits down over coffee to discuss the film and his membership in the vast tribe of Bruce fans.

It is weird, Manzoor says, to see your life on screen, even if the fictional one diverges from the real one. The movie, for instance, leaves out his older brother, presents his mother as fluent in English and shows him actively arguing with his father, none of which is real. But the story is mostly true, he says, “emotionally autobiographical” in the way Springsteen’s songs are.

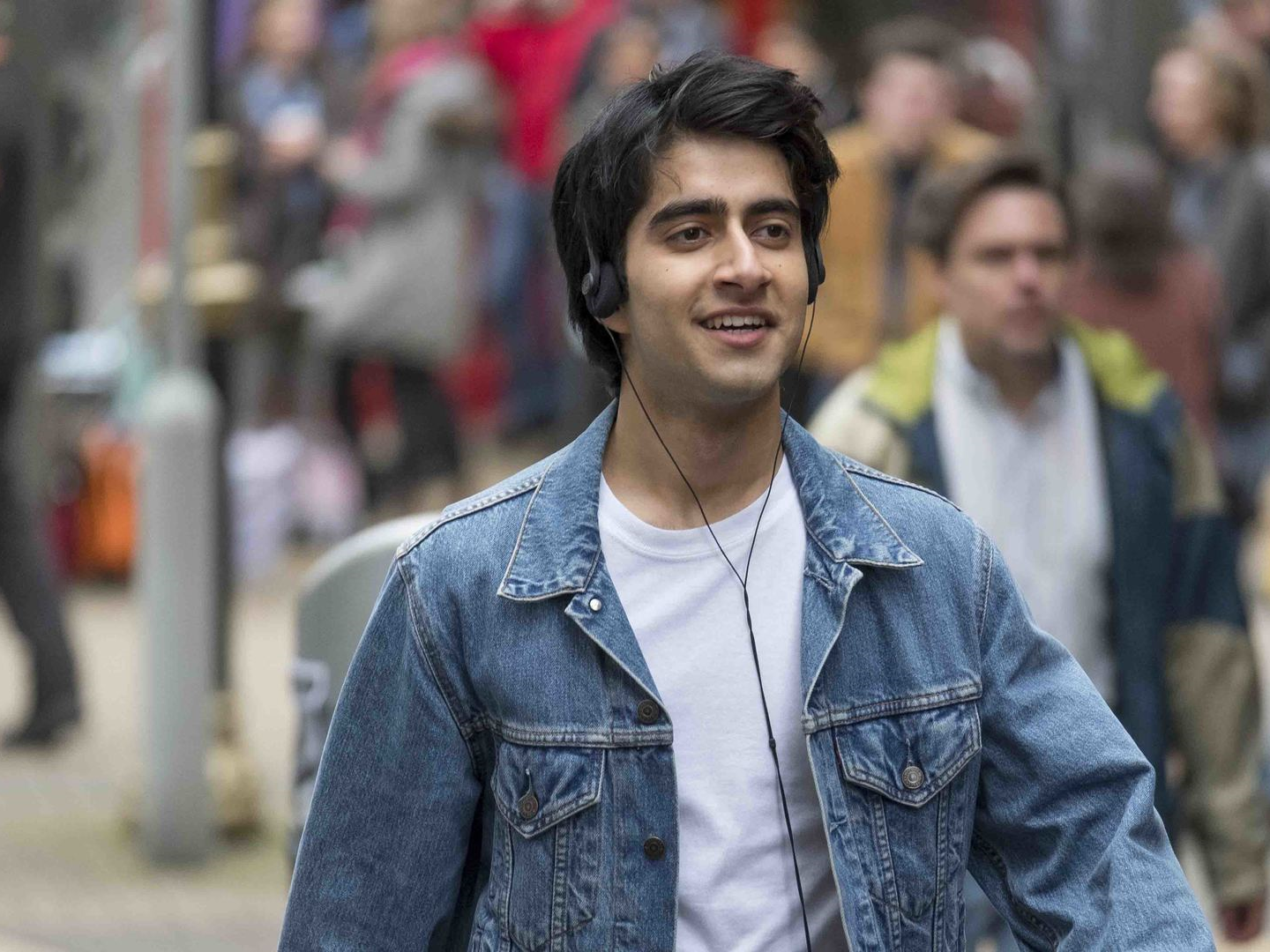

“My mum really did make clothes until 1 in the morning,” just as his movie mother does, he says. “My dad really did work at Vauxhall until he got laid off, and he really did wear suits to the job centre” when he looked for a new job that never materialised, he says. And the teenager in the film, played by Viveik Kalra, is called Javed, which is Manzoor’s family nickname.

It is not realistic, obviously, to think that the people of Luton have a habit of breaking into Bollywood-style dancing in the streets. But that was a way the director helped incorporate Springsteen’s music and words into a film meant to tell the story of a young man yearning to be a writer and transformed by music. (This is another reality tweak. Back then, Manzoor wanted, if he wanted anything at all, to be a DJ.)

“I didn’t want to make a jukebox musical,” Chadha says. “The film is about writing and words.”

“The pressure was to take that idea of writing and make it dramatic,” she says.

Take her approach to “Dancing in the Dark”, the gateway song that brought new fans to Springsteen in the mid-Eighties with a catchy tune and a jaunty video featuring an as-yet-unknown Courteney Cox. Just as “Born in the USA” can be misconstrued as upbeat and patriotic when it is really about dead-end jobs and unemployment, so does “Dancing in the Dark” fool you until you know what it says. In the movie, the lyrics pour across the screen, as intimate and immediate to Javed as the poetry he has been secretly writing.

“People might listen to ‘Dancing in the Dark’ and go, ‘What a great song,’” Chadha says. “But when you listen to the words, it’s a song about alienation and a kid feeling out of step with where he is, hating himself and wanting to get out, feeling that something better is happening somewhere else.” (In other words, the way all teenagers feel.)

I would come home from school and play his records all night

Chadha and Manzoor have known each other for a long time, but Chadha made it clear that in order to make a film of Greetings From Bury Park, they would “have to get Bruce on our side” and eventually secure permission to use his music.

In 2010, Springsteen came to London for the premiere of The Promise, a documentary about the making of the album Darkness on the Edge of Town. Chadha took Manzoor along as her guest.

By this time, Manzoor had been to more than 100 Springsteen concerts, and Springsteen had begun to recognise him as a superfan. (He stood out for being Pakistani, having big hair and positioning himself near the front.) On the red carpet, the singer unexpectedly spoke to Manzoor. “He said, ‘I’ve read your book, and it’s amazing,’” Chadha says.

After everyone stopped hyperventilating and went home, they began slowly to work on the screenplay (Manzoor and Chadha share credit with Paul Mayeda Burges, her husband and longtime collaborator). Then Chadha went off and made her next film, historical drama Viceroy’s House, putting the project on hold for a few years.

“And then Brexit was happening,” she says, “and it was very ugly. The world was turning into quite a divisive place. And I said, ‘I’m going to pick up this project, and I’m going to put all my frustration about the world in here.’ ”

There was still the question of the music. In 2017, Manzoor sent an impassioned email to Springsteen, pleading his case. Springsteen said yes, and so 12 of his songs – “Badlands”, “Thunder Road” and “Hungry Heart” among them – appear in the film.

The movie has particular resonance now. Anti-immigrant nationalism is again on the rise in Britain, just as it was in 1987, and race relations in the US are increasingly ugly and violent. Blinded by the Light offers a nostalgic look at the sort of American values – tolerance, open-mindedness, inclusiveness, optimism – that sometimes feel like relics of another time.

“The thing that is touching to me, and sad, is the role that America plays for me,” Manzoor says. “When I was 16 I truly looked to America as the promised land. I thought, ‘If it gets too bad in this country, I can just go there.’”

In one scene in the film, drawn directly from real life, US immigration officials question the young Javed as he arrives in New Jersey to visit Springsteen’s home town. Their response shows how thoroughly love of Springsteen transcends what might seem to be unbridgeable differences of race and age and nationality. Talking to people about the movie has reminded Manzoor of this again and again.

Recently, he related, a couple from New Jersey approached him after an advance screening of Blinded by the Light.

“They said, ‘You’re just a Pakistani version of us.’”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks