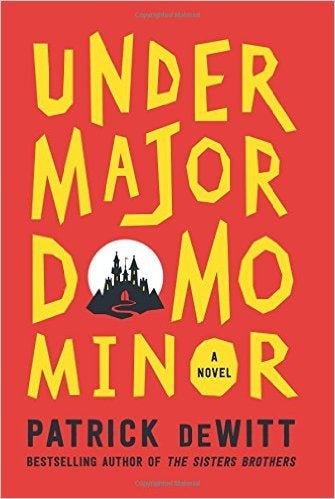

Under Majordomo Minor, by Patrick deWitt - book review: Here’s Lucy, in a labyrinth

Granta Books - £12.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his previous book, the hugely entertaining The Sisters Brothers, Patrick deWitt had great fun playing with the conventions of the Western: an Eeyore of a steed, a whining assassin who ends up moving back in with his mother . With Undermajordomo Minor, deWitt pitches his take on the Gothic folk tale somewhere between Kafka and Young Frankenstein.

The undermajordomo – that is, assistant to the assistant – of the title is young Lucy Minor. True to deWitt’s tendency to meddle with expectation, Lucy is a man. Though not much of one, as far as his fellow villagers are concerned. We meet him as he prepares to leave his mother’s home for employment in the castle of Baron Von Aux, the start of what appears to be a coming-of-age story in which Lucy’s character will be forged, his life education complete.

What follows is nothing of the sort. It’s almost Seinfeld-ian, in fact – no hugging, no learning. No hugging to such an extent that, rather than bid him a fond farewell as he tarries outside his home, his mother shakes a rug over his head, utterly indifferent to his continued presence.

No learning? Certainly, Lucy never quite grasps that the incessant lying he tells to squirm through situations inevitably leads to worse trauma. Then there’s his struggle to understand his new surroundings – not least why there is a war going on around the castle. To be fair, no one ever quite wants to explain the causes of said conflict. Why? “Long story,” a newfound companion tells him. “And what is the story?” “It is most complicated and long.” “Mightn’t you tell it to me in shorthand?” “It would never do but to tell it in total.” “Perhaps you will tell it to me later.” “Perhaps I will …. Though likely not. For in addition to being a long story, it’s also quite dull.”

Questions – and tension – are left in the air; in this matter; in the psychological condition of his employer; in the case of his new love; even, perhaps especially, in the manifestation of a Very Large Hole – a Chekhov’s gun, if ever there were one.

Tension maybe, but this is an effortless read, filled with the most wonderfully idiosyncratic characters, not least Mr Olderglough, the assistant whom Lucy is assisting, and whose intensely formal yet warm conversations with his apprentice are an eccentric highlight.

Less gratifying than The Sisters Brothers? Perhaps so, in its very refusal to resolve matters – but that is not to say it is any less accomplished; and certainly no less fun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments