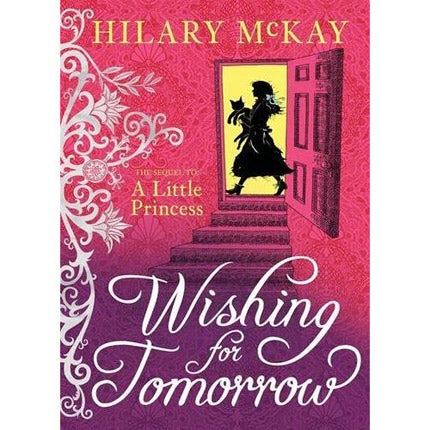

Wishing for Tomorrow, By Hilary McKay

Life goes on for the little princess

Frances Hodgson Burnett's A Little Princess is one of the greatest Cinderella stories of all time. It describes how Sara Crewe is set to work as a skivvy in her former school after the disappearance of her financial support.

Published in 1905, it now has a sequel by Hilary McKay, a prize-winning children's author of great talent. Everything should be set fair, and Wishing for Tomorrow is indeed a delightful story, well worth reading at any age.

But rather than following the fortunes of Sara, McKay focuses on minor characters whose fates until now remained tantalisingly obscure. It is as if a sequel to Nicholas Nickleby detailed what happened to the rest of the pupils at Dotheboys Hall after the transportation of Wackford Squeers.

McKay's main character is Ermengarde St John, the slightly dim but sweet-natured child who was friendly to Sara. Marooned like the other girls in an establishment that retained neglected children during the holidays, Ermengarde writes wonderfully funny and revealing letters to the absent Sara, but is too shy to send them, wrongly believing her friend has rejected her.

She has good support from eight-year-old Lottie, a natural anarchist, and Alice, the equally determined new maid from Epping. Against this pair, even the rich, popular and mean Lavinia Herbert finally finds her match. As for Miss Minchin, the cold-hearted headmistress, she becomes so marginalised that her death is almost an anti-climax.

By this time, Sara has made an affectionate re-appearance and Lavinia has decided to work for university rather than continue bullying. Ermengarde is re-united with her aunt Eliza, who decides to run a friendly boarding house for the girls, now much more happily attending day schools. Wittily illustrated by Nick Maland, packed with humour and just enough heartache to keep readers involved, this charming novel is a real treat, with eccentricity replacing the original's cruelty and silent suffering giving way to defiant stoicism.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks