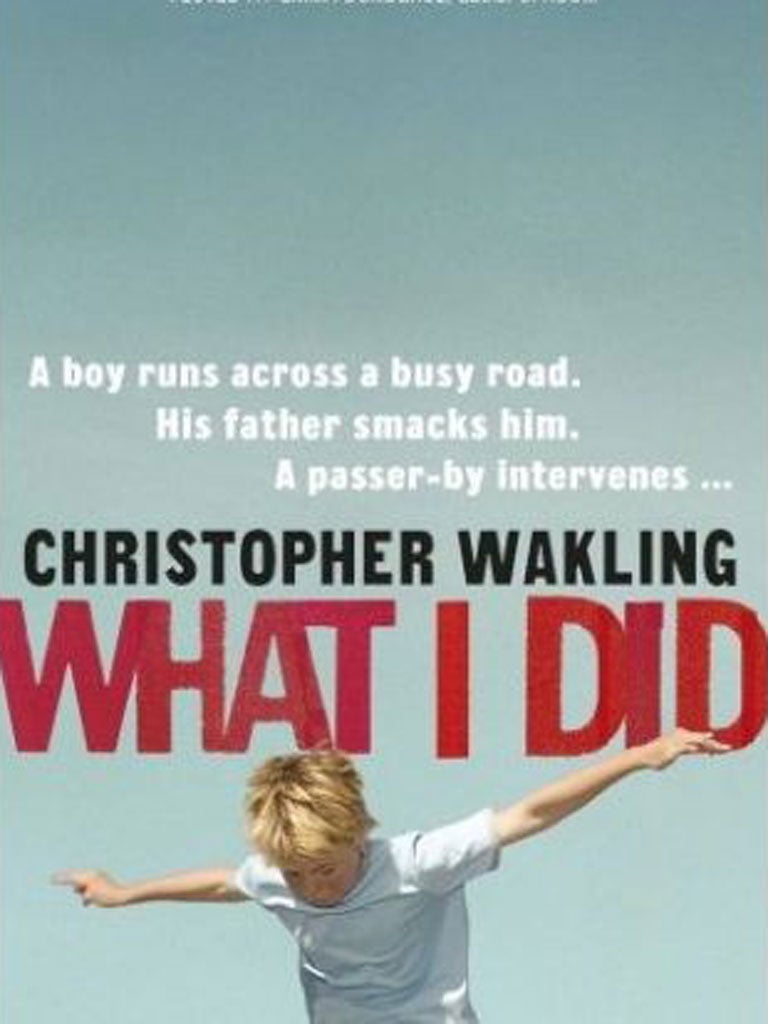

What I Did, By Christopher Wakling

Family affair fuelled by raw emotion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From Molesworth to Adrian Mole, English literature is crammed with memorable schoolboy narrators. More recently, the tots have been demanding our attention. In Room, Emma Donoghue gave voice to a precocious five-year-old; and, in his sixth novel, Christopher Wakling acts as ventriloquist to the kindergarten classes with a horribly plausible journey into the mind of a six-year-old boy.

Billy Wright isn't on the special-needs spectrum, nor is he intentionally difficult. It's just the "electricity" he feels "fizzing" in his arms and legs that compels him to tip back on chairs and slam into walls. This same energy causes him to slither free from his coat sleeve and out from under his father's grasp, and make a dash across a busy main road. Billy's father, after a morning of spilt drinks and trailing shoelaces, pulls down his son's trousers and smacks him across the buttocks "very, very, very hard".

As in Christos Tsiolkas's novel, The Slap, the ensuing drama is less about politically incorrect parenting than how a family cope with the fall-out of a public violation. Billy's slap is witnessed by a concerned bystander who informs social services, and so the family's nightmare begins. A visit from a child protection officer follows, but thanks to a series of tragicomic coincidences it escalates into something far more serious. As he puts his own oblique slant on events, Billy's incomplete understanding only serves to underscore the bigger picture.

In Wakling's hands, life at boy-level becomes a vivid and contradictory place. Enriching Billy's observations – "Zips are a right pain"; "God is a segment of the imagination" – is his encyclopaedic knowledge of the animal kingdom. With the help of old David Attenborough DVDs, he attempts to classify his own family's behavioural ticks. His mother becomes a prairie dog ("she's never tiring!") while his cousin, Lizzie, is an owl: "She does have huge eyes and she doesn't say anything much except oooh."

Life in a small head can feel claustrophobic, but Wakling ratchets up the narrative tension by challenging us to identify the real monster of the piece. Is it Billy's father – whose angry "son!" slices through the text – or Billy himself, who knows enough to understand when his dad is "quite pleased" to have a "proper reason" to be cross with him. The novel brilliantly captures parent-child relations in the raw and the emotions that even the most experienced social worker can't tame.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments