Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain, By John Darwin

Conflict and paradox marked our imperial age. This masterly overview debunks many myths about it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After almost all remnants of that famous pink quarter of the map were disposed of in the 1960s, a great silence descended upon the subject of the British Empire. Like Eliot's typist in The Waste Land, most of the British seemed to sigh: "Well now that's done: and I'm glad it's over". Today, all of a sudden, it's an open topic once more. Jeremy Paxman trawled the territory for a BBC series and a book suggesting that the Empire might not have been altogether a bad thing. Historians like Niall Ferguson go further in asserting its worth.

But it's early days for reassessment: empire was missing from Danny Boyle's Shakespeare-plus-workshop-of-the-world scenario for the Olympics and William Hague skated breezily over the subject in his recent upbeat assessment of Britain's place in the world: "I think we should just relax. It's a long time ago." Tell that to the Kenyans still trying to get justice in the High Court for British atrocities during the 1952-60 Mau Mau emergency.

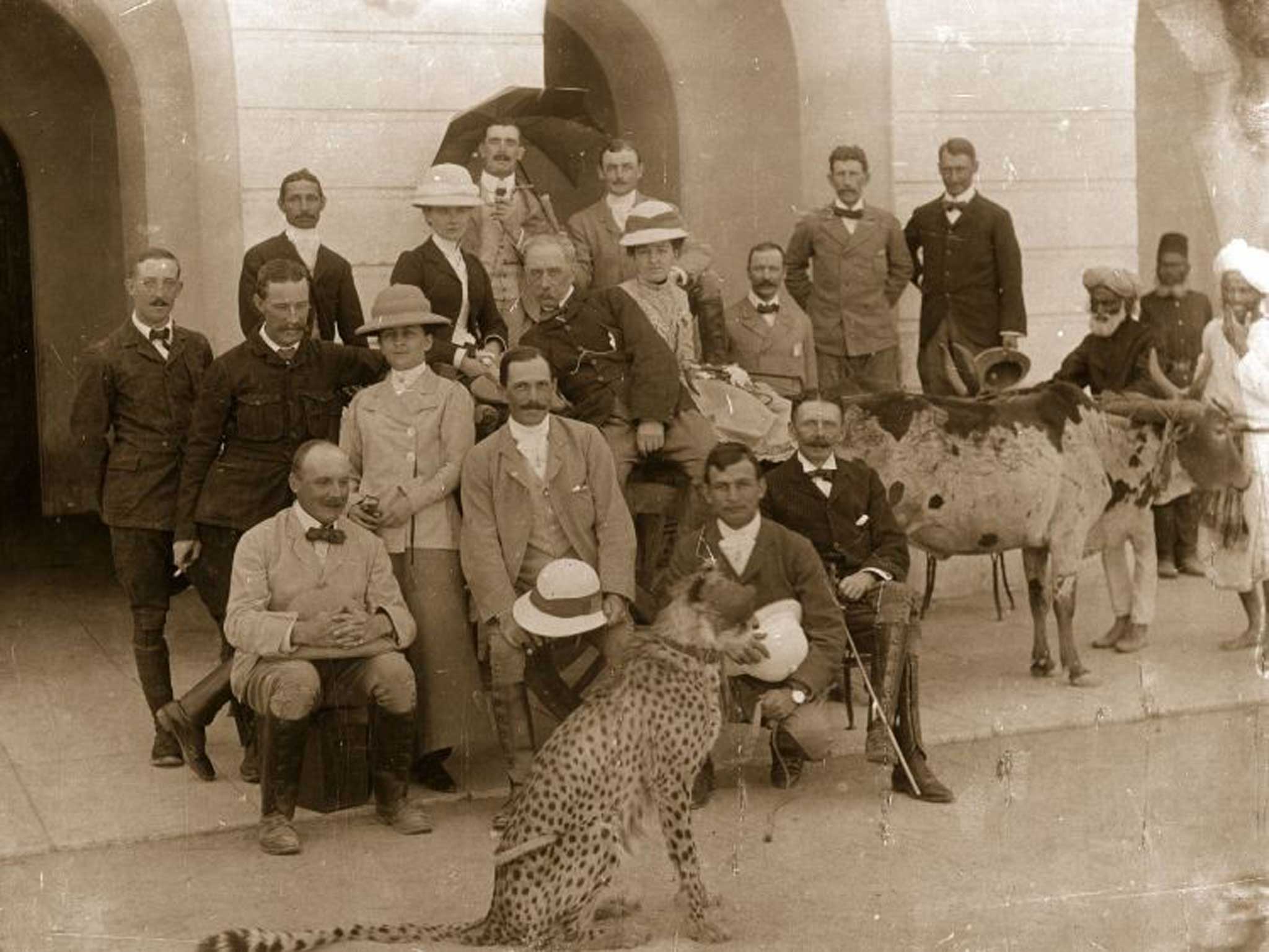

John Darwin, an Oxford historian, is not a propagandist or apologist for empire. He is more concerned to show that the conventional idea that the British Empire was a monolith is false. In fact, the empire always was a work in progress and a hotchpotch of very different kinds of enterprise.

There were essentially three types (and many anomalies): settler states (America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand); India (a case apart, with its uneasy divide-and-rule between many princely states); extractive states often employing slave labour (the Caribbean). South Africa was a dangerous anomaly with the majority of its white minority population Dutch rather than British.

Darwin organises his book thematically, creating a certain amount of repetition, but it does enable him to explain vividly the trading patterns, the systems of governance, the military tactics. Darwin is excellent on the conflicts between the early mercantilist philosophy (up to 1815), which insisted on monopoly and suppression of both free trade and rival industries in the colonies, and the Free Trade of the Victorian imperial high point. Perhaps the most enduring feature of the British empire was the globalised system of commodity trading, finance, transport and communications, which survives to this day, albeit without Britain in the driving seat.

Unfinished Empire is an immensely valuable corrective to some very loose thinking. There are tantalising hints that could have been followed further. Between 1815 and 1914 more than twice as many people emigrated from the British Isles than from any other European country.

Darwin cites the British "propensity to migrate" but this is statement of fact not an explanation. Britain is a north-western European country and the inexorable shift in the balance of power from Mediterranean Europe between the Classical period and the heyday of the empire was a large demographic movement of which Britain partook.

British migration wasn't only spurred by poverty. One of our principal rivals in colonisation was Holland, another small north-west European nation with people to spare. Population pressure in northern Europe derived from its exceptionally favourable farming environment, a pump-primer for the Industrial Revolution as well as a spur to empire.

Why it was Britain rather than Holland that reaped the greatest reward requires a lot more detailed analysis, but it should start from that deeper history and geography. As Darwin explains, Britain's lead in the Industrial Revolution, united with a growing empire, proved an irresistible combination until America and Germany began to catch up and then to overtake.

Peter Forbes's book 'Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage' is published by Yale University Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments