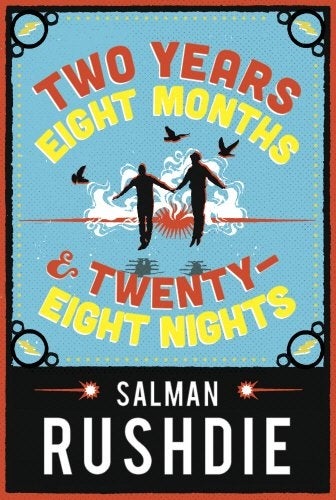

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights, By Salman Rushdie - book review: Imagining Islam’s battle with secularism

Jonathan Cape - £18.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Salman Rushdie’s 12th novel tackles a subject close to his heart – the battle between fundamentalist Islam and the three-pronged fork of secularity: reason, logic and science. The title adds up to 1,001 nights, an allusion to the story of Scheherazade, and although there are not 1,001 strands of story here, there are many, and they are colourful and compelling. Rushdie’s last book, the memoir Joseph Anton, told about his life in hiding after the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa. Here, Rushdie uses the fantastical elements that have occurred in some of his previous work to illustrate this battle.

The real-life 12th-century philosopher and physician Ibn Rushd is sometimes seen as the forefather of secular thought, and admiration for him spurred Rushdie’s father to adopt his name. Rushd was, for a time, exiled and his books burned – like Rushdie himself in some quarters – when his philosophy fell out of favour. He advocated cause and effect, analysed Aristotle and argued against the teachings of another philosopher, Ghazali. Ghazali believed that God created and controlled everything and that philosophy was a blasphemy.

The narrator of the novel looks back from a time in the future and tells how a jinnia, a female jinni (or genie) named Dunia (a similar name to Scheherazade’s sister) loved Ibn Rushd and gave birth to many of his children. Around 800 years later, near the end of the 20th century, a breach occurs between the worlds of the jinni and the mortals and Dunia reappears. A fierce battle ensues between the evil, or dark, jinni and Dunia, and she enlists the help of her human descendants to help. The dark jinni have the characteristics of the Taliban and Islamic State, wanting to ban music, art, free speech, journalism, and laughter, and to curtail women’s rights. One, modelled on Bin Laden, watches porn. The others have womanised, gambled and broken their own edicts earlier in their lives.

Dunia’s descendants include a gardener who floats above the surface of the ground owing to the anti-gravitational powers of Zabardast, a dark jinni; a graphic artist named Jinendra, who dreads becoming an accountant like his boring cousin; and a baby with the power to root out corruption. Rushdie displays the wry humour that helped make Midnight’s Children such a masterpiece: Jinendra’s cousin is so conformist that he changes his name to Normal, while the equivalent of the sat nav on Dunia’s magic carpet goes awry at one point. I longed for more of this playfulness and less of the fantastical action. There is also the paradox of using magic realism to illustrate the battle between fundamentalist Islam and reason, in that by definition it involves invoking magic – anathema to reason and science. Meteors here, for example, are the work of evil jinni. But then, as our narrator says: “To recount a fantasy, a story of the imaginary, is also a way of recounting a tale about the actual.” And the struggle invoked by Rushdie’s vivid allegory is one all too familiar to most rationalists.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments