Tormented Hope, By Brian Dillon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the second part of his Essay on Man, Alexander Pope, after asserting that "The proper study of mankind is Man", describes dithering humanity which "hangs between, in doubt to act or rest;/ In doubt to deem himself a God or Beast;/ In doubt his mind or body to prefer". Brian Dillon's illuminating, humane and beautiful book considers hypochondria: precisely that toppling overfall where mind and body contend for preference. His nine case studies of "hypochondriac lives" provoke wonder without ignorance, laughter without mockery and grief without sentimentality; his territory, the still-inexplicable relationship between ourselves and our selves.

Our dubious sanity depends on ignorance, inner and outer. A man comprehensively aware of his body, from liver to lymph, would go as surely mad as one who could perceive all the operations of the cosmos. But the hypochondriac believes, even knows, that he lives in close intelligence with his body, and the news is not good. It is not the cancer-phobia, the impossible allergies and the food intolerances of the Western "worried well", but the certainty that something is wrong, that some terrible dissolution or metamorphosis is already in train.

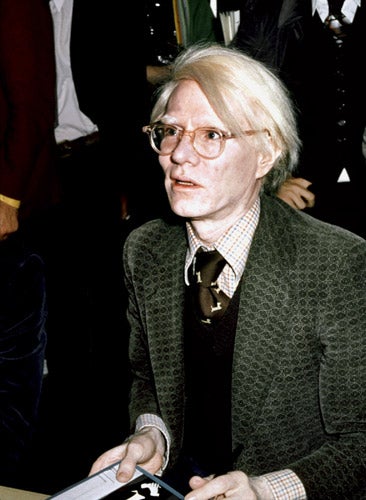

Dillon's task is to mediate between us and his subjects (clients? patients?) to show us both that they are not merely worried but, in their own terms, right, and to tease out what purpose their being right might serve . Andy Warhol's need to don his wig and "glue myself together" before going out suggests to Dillon "the more generalized fear that he might come apart in public if he is not vigilant enough, that his sense of his physical self is still precarious and provisional." The great pianist Glenn Gould's humming and twitching, his hatred of eating and being touched, are efforts "to become, in effect, the ghost of himself." James Boswell, miserably holed up in Utrecht, suffers with his spleen, his vapours, self-exhortations and his terror that he will "dissolve"; but all these may be "a structuring principle masquerading as chaos, resolve disguised as fear".

Here is Charlotte Brontë, laid low with fashionable hypochondria, but genuinely laid genuinely low, suffering "advanced torment [which] in its most dramatic and richly-imagined forms seems even to have defined a late version of the Gothic imagination and a vision of the creative temperament stymied, isolated or in exile". Here is Charles Darwin with his "flatulence" occupying "his half-century of co-tenancy of my fleshly tabernacle", his hydrotherapies at Malvern and elsewhere, "living in Hell" and covered in rashes and "fiery Boils". "Darwin," writes Dillon, "did not live wholly in the world whose view of itself he altered for ever."

Here is Marcel Proust, awash with drugs, choking under his asthma powders in his cork-lined room; here is Florence Nightingale, who "presents such an array of ailments, obscurely bound up with fear, resignation and a desire for control, that it is hard to say where her physical suffering ended and its psychological ramifications began."

Saddest of all is Alice James, in whom "the only theatre in which the private dreams of the constrained female psyche could then be performed was the female body itself," and whose hypochondria "consisted in allowing herself to be just ill enough not to have to face the creative and emotional void at the heart of her short life".

Finally vindicated by a "real" diagnosis - breast cancer - she wrote that she would regret living to see brother Henry's triumphs as a playwright (which never came) and her pride in "William's Psychology, not a bad show for one family! Especially if I get myself dead, the hardest job of all." She did. William spoke of his sister's "little life" but, says Dillon, it had more precisely "been the problem of how to sustain a voice, a personality or a self... Her illness had been as much her literary subject matter as mind and morals had been for her brothers."

Strangest of all is Daniel Paul Schreber, a German lawyer who believed he "had been chosen by God to give birth to a new race of men [and] was slowly being transformed into a woman". Subject to invisible rays, "the grisly splendour of his imagination is a reminder... of the long history of delusions regarding the body," including the men in classical antiquity who believed themselves made of earthenware and, when it became more commonplace, of glass.

Schreber believed he had been invaded by "little men" who attempted to pump out his spinal cord; that his stomach suddenly vanished in the middle of meals; that "his organs have been damaged or destroyed so many times, and so often restored, that he doubts his own mortality."

The sense of contested mortality, of uneasiness with or terror of one's own incarnation, is the theme of Dillon's book, nor does he judge those caught in the whirlpool. His is not the witless menagerie of the tabloid or reality TV. Despite, or because of, that, Tormented Hopes is not a book you can't put down. It is a book you will keep putting down, both to absorb what he has said and to postpone reaching the end. There is no higher compliment.

Michael Bywater's 'Big Babies' is published by Granta

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments