The Tell-Brain: Unlocking the Mysteries of Human Nature by VS Ramachandran

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

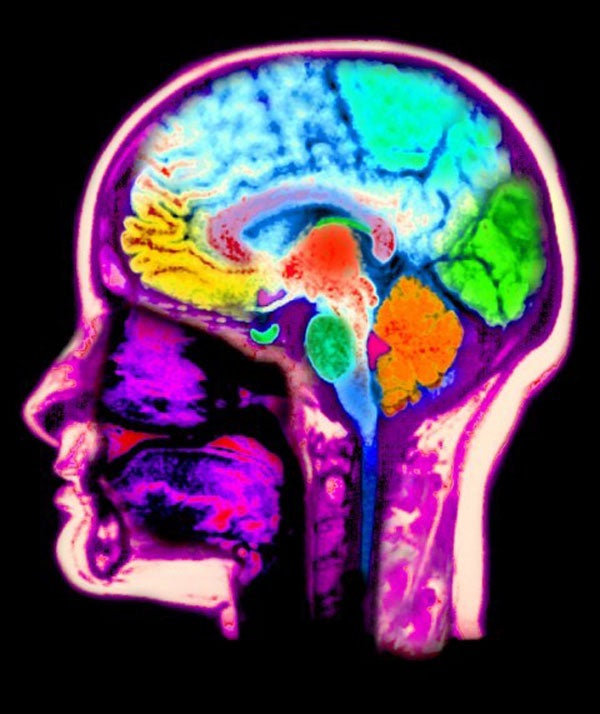

Your support makes all the difference.Neuroscience is a frustrating business. Modern research has done a wonderful job of mapping out the overall organisation of the human brain, yet the details of the machinery remain mysterious. We know which brain region is responsible for face recognition, and which understands word meanings, and which takes care of decisions, and so on. But nobody has any idea how these clever tricks are done. Much of our knowledge comes from brain injuries. Localised damage to the brain can cause very specific disabilities. There are people who have lost the ability to see motion, even though their vision is otherwise normal, and people who can no longer speak grammatically, even though they can comprehend others perfectly well.

The injuries suffered by these unlucky souls provide an obvious guide to the brain's layout. In the past couple of decades, the resulting picture has been confirmed by brain imaging techniques which show which areas of the brain are switched on by which mental activities.

Unfortunately, this detailed topography only serves to highlight how little we know of the mechanisms involved, other than that they must depend on billions of nerve cells shuttling signals back and forth. In the early days of the computer revolution, many psychologists hoped the brain could be shown to work along the lines of a digital computer. But this research programme has proved fruitless. Conventional computer programs are hopeless at many things our brains cope with effortlessly, like understanding languages or making decisions. Our brains must work differently, but exactly how is anybody's guess.

VS Ramachandran's new book displays both the strengths and weaknesses of contemporary neuroscience. He is good on topics that depend on cerebral organisation, but weaker when specific mechanisms are at issue. An eminent neuroscientist, Ramachandran is a versatile populariser who draws many interesting lessons from his research. But once he moves away from the safe ground of brain topography, he finds it hard to avoid hand-waving speculation.

Ramachandran is best known for his work on the "phantom limbs" of amputees. According to orthodoxy, these ghostly appendages manifest themselves because irritated nerves on the stump fool the brain into thinking the limb is still there. Ramachandran showed that this is the wrong explanation. Rather, the amputation causes the area of the brain that originally monitored the lost limb to start responding to adjoining brain regions. For example, the brain area that monitors the arm is next to that for the face, and so once the arm is lopped off, it begins reacting to facial nerve messages. Ramachandran was able to produce feelings in phantom arms by stroking his patients' faces. Similarly, the brain area for the foot is next to that for the genitals. As a result, some foot amputees report that they can experience orgasms in their feet.

More recently, Ramachandran has been studying "synesthesia". Many artists report seeing numbers, or letters, or faces, as having distinctive colours. Nabokov wrote of the "alder-leaf f, the unripe apple of p, and pistachio t". But psychologists have tended to be sceptical, suggesting that these artists are making a mountain out of ordinary memory associations, like those triggered by Proust's madeleine.

An elegant experiment by Ramachandran shows that the phenomenon runs deeper. He asked subjects who report seeing numbers as coloured whether they could pick out a few black "2"s from an array of similar-looking black "5"s. For ordinary people this would be a laborious process. But the synesthetic subjects could pick out the "2"s immediately, just as if they really were coloured differently from "5"s.

Why should different senses get muddled up in this peculiar way? According to Ramachandran, it depends on brain geography once more. The region of the brain that registers colours is right next to the one that deal with numbers. He hypothesises that in certain subjects these two regions get "cross-wired" and set each other off. This idea is further confirmed by the proximity of other brain areas implicated in synesthesia, like those for recognising letters and faces.

Ramachandran is less convincing when he turns to "mirror neurons". It has long been known that certain nerve cells in the motor cortex of monkeys fire when they execute specific actions, like pulling a lever or grabbing a peanut. But about ten years ago, researchers discovered that some of these neurons also fire when the monkeys observe other monkeys performing the same actions. This has caused a great stir in the neuroscientific world. These "mirror neurons" have been widely hailed as a possible basis for empathy, culture, and many other human attributes.

Ramachnadran is no exception to this general enthusiasm. His specific suggestion is that mirror neurons played a crucial role in the evolution of language. But in truth, as he himself acknowledges, this is little more than guesswork. The trouble is that nobody really knows what mirror neurons do and whether they are important. Since we have little idea of how batteries of neurons combine to weave their magic, it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from the firings of individual cells.

Still, his speculations are never less than interesting. He does not stop with language. Later chapters cover consciousness and the nature of art. He is full of ideas and can illustrate many with tales from his neuroscience experience.

Most striking are the delusions that can arise when the brain goes awry. We meet a patient convinced that his poodle is an impostor, one who is accompanied everywhere by his phantom twin, and even one who is sure he is dead. All this is fascinating stuff. It is just a pity that Ramachandran can't tell us more about the brain's basic mechanisms.

David Papineau is professor of philosophy at King's College, London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments