The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain, By Paul Preston

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

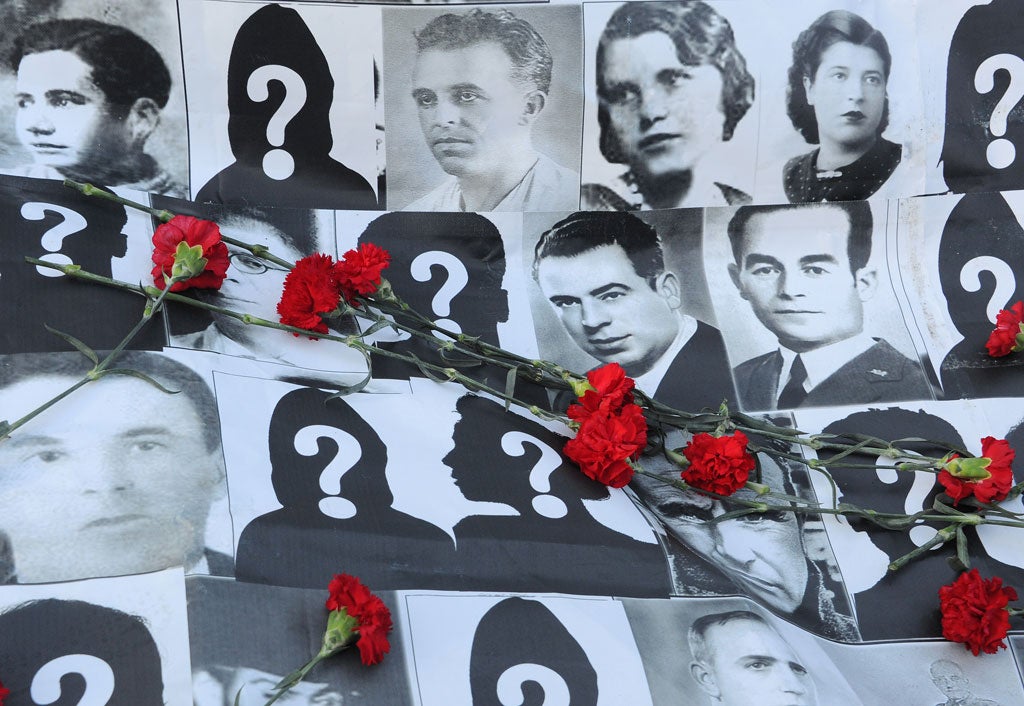

Your support makes all the difference.In Spain today, the civil war triggered three quarters of a century ago is still "the past that has not passed away". When a Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, internationally renowned for his championing of human rights, opened an investigation into the conflict's core of extreme extrajudicial violence (in which more than 200,000 people were killed), he was charged with abuse of power. Although Garzó* was acquitted this week, the fact both that he was put on trial at all and that judicial investigation into the violence is now blocked leaves unresolved the vehement memory polemics of Spain's civil society, and so renders Paul Preston's monumental, rigorous and unflinching study important and opportune in ways that reach far beyond the purely academic.

Preston is Britain's foremost historian of modern Spain. He acknowledges his debt to those historians inside Spain who over the past three decades, despite huge social and political obstacles, have opened up the facts of this violence through painstaking research in local archives.

But Preston's own contribution is a major one, both in tracing the fundamentalist origins of the military coup that unleashed the killing and in reconstructing its complex consequences. What the conspirators intended was to crush the social challenge posed by the reforming project of the democratic Second Republic. They and their supporters – whether patrician elites, conservative townsfolk or inland peasantry – saw it as heralding the end of a cherished and familiar world; indeed as the end of "Spain".

From the beginning, Preston "reminds" us that while the conflict in Spain evolved into the "war of two equal sides", as subsequently enshrined in Western consciousness, it began in July 1936 as something very different. It was a military assault on an evolving civil society and democratic regime in the name of the "true nation", in defence of which the rebels were prepared to kill, or "cleanse", as their rhetoric proclaimed. General Queipo de Llano, whose troops laid waste to south-western Spain, called it "the purification of the Spanish people".

Recognising that the initial massive violence was generated by the military rebels themselves remains the biggest taboo of all in democratic Spain's public sphere. Franco's dictatorship has never been delegitimised since his death in 1975, notwithstanding the symbolic measures of recent years. It is this military responsibility, which Garzó* sought unsuccessfully to confront, that lies at the heart of Preston's study. He builds on a lifetime's research into the destruction of democracy in 1930s Spain to show how a military-led coalition against political and social reform triumphed, against the divided and inexperienced centre-left government of the Second Republic.

The conspirators' determination to deploy terror from the start was made clear in the prior orders of the coup's director, General Mola, to "eliminate without scruples or hesitation all who do not think as we do". Their aim was to reverse both the Republic's redistributive policies of land and social reform, and the cultural shift implied in its extension of literacy, co-education and women's rights. But resistance to the rebels in much of urban Spain created such logistical challenges that the coup would likely have failed, had it not been for the provision by Hitler and Mussolini of the aircraft that transported Franco's colonial Army of Africa to mainland Spain. This gifted the rebels the brutal force which effectively rescued the failing coup.

The military rebels now unleashed the mass slaughter of civilians. Preston's book tells the harrowing story of this "cleansing" war of terror as it unfolded across the entirety of Spain's territory. Even in areas where there was no resistance to the coup, the new military authorities presided over an extermination, mainly perpetrated by civilian death squads and vigilantes, of those sectors associated with Republican change. The victims were not only the politically active, or those who had directly benefited from reform, but also those who symbolised cultural transformation: progressive teachers, self-educated workers, "new" women.

As Preston shows, all these sectors were perceived by the army's rebel commanders as akin to insubordinate colonial subjects. His use of "holocaust" in the book's title will rightly spark debate. But Preston's intention is not to equate Spain with the Holocaust. Rather he wishes to effect a category shift in how people think about what actually happened in Spain, in order to suggest parallels and resonances between the cases which allow a deeper understanding of Europe's dark mid-20th century as a whole, and of the mechanisms of human violence itself.

Even in the areas of Spain where the military coup failed, in one crucial respect it "succeeded" fully. There too it unleashed extrajudicial killing which, combined with the killing in the rebel zone, would change Spain's political landscape forever. In Republican territory this killing, which for a time the government was powerless to prevent because the coup had collapsed the instruments of public order, was perpetrated against civilian sectors assumed to support the coup. Some 50,000 people were killed, including nearly 7,000, mostly male, religious personnel.

These killings drastically undermined the Republic's international credibility – even though, as Preston reminds us, it was the coup itself that conjured the killing, creating the conditions that made it possible. Republican-zone violence was as ugly and unscrupulous as that of the rebels; it was, of course, also reactive. But once in existence it took on a life of its own. By the time that the Republican authorities were able to rebuild public order and put an end to this killing, it had already reinforced support for Franco among the families of its victims.

After Franco achieved victory in spring 1939, the mass-murdering dimension inherent in war-forged Francoism became fully apparent, as the final section of Preston's study explores. Of the baseline figure of 150,000 extra- and quasi-judicial killings for which it was responsible in the territory under direct military control between 1936 and the late 1940s, at least 20,000 were committed after the Republican military surrender in late March 1939.

In a bid to create the "homogeneous" nation of which the conspirators dreamed, based on traditionalist values and social deference, the regime engaged in the killing, mass imprisonment and social segregation of the Republican population. To do so, the regime exhorted "ordinary Spaniards" to denounce their compatriots' "crimes" to military tribunals. Tens of thousands did so – out of a combination of political conviction, grief and loss, social prejudice, opportunism and fear. Thus did the Franco regime, born of a military coup that itself triggered the killing, pose as the bringer of justice. But this was "justice turned on its head", given the notorious lack of fit between the acts of wartime violence themselves and those denounced and tried for them. No corroboration was required nor any real investigative process undertaken.

But, as Preston shows, matching culprits to crimes was not the real point of the exercise. Tens of thousands were tried merely for their political or social alignment with the Republic. As one prosecutor declared: "I do not care, nor do I even want to know, if you are innocent or not of the charges made against you." This was the Franco regime's "fatal" moment.

Through its choice of legitimising strategy it mobilised a social base of perpetrators, building on their fears and losses during the war, while, at the same time, it criminalised the Republican population, perpetrating an abuse of human rights on a vast scale.

Worse still, the regime, buoyed up by the Cold War, then kept alive these binary categories for nearly 40 years, through its apartheid policies and an endlessly reiterated discourse of "martyrs and barbarians". This is what marks Francoism apart – the lasting toxicity of its originating strategy, which still burns the social and political landscape of 21st-century Spain, three and a half decades after the dictator's death.

That Spain's public sphere is still shaped by the values and perceptions bequeathed by four decades of Francoism is blindingly evident in the Garzó* case. Inside Spain, the afterlife of violence remains; and with it the need for a democratic coming-to-terms, inherent in which is an openness to the difficult past. Preston's study is history as a public good, a substitute for the truth and reconciliation process that has not taken place in Spain and an antidote to those who still regard Franco as a good Christian gentleman.

That this remains unfinished business is clearly indicated by the child-trafficking scandal recently exposed in Spain, whose origins stretch back to the dictatorship's criminal social-engineering policies. The picture is clear: the victimised social groups are the same as those who, in 1936, were subjected to the military rebels' "prophylaxis".

Helen Graham is professor of modern Spanish history at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her new book, 'The War and its Shadow', will be published by Sussex Academic Press in May. Paul Preston will be speaking at the 'Independent' Bath Literature Festival on Wednesday 7 March (bathlitfest.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments