The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory, by John Seabrook - book review: Bubblegum pop with a flavour of vodka

An eminently readable study but one which regards music through a too-white prism

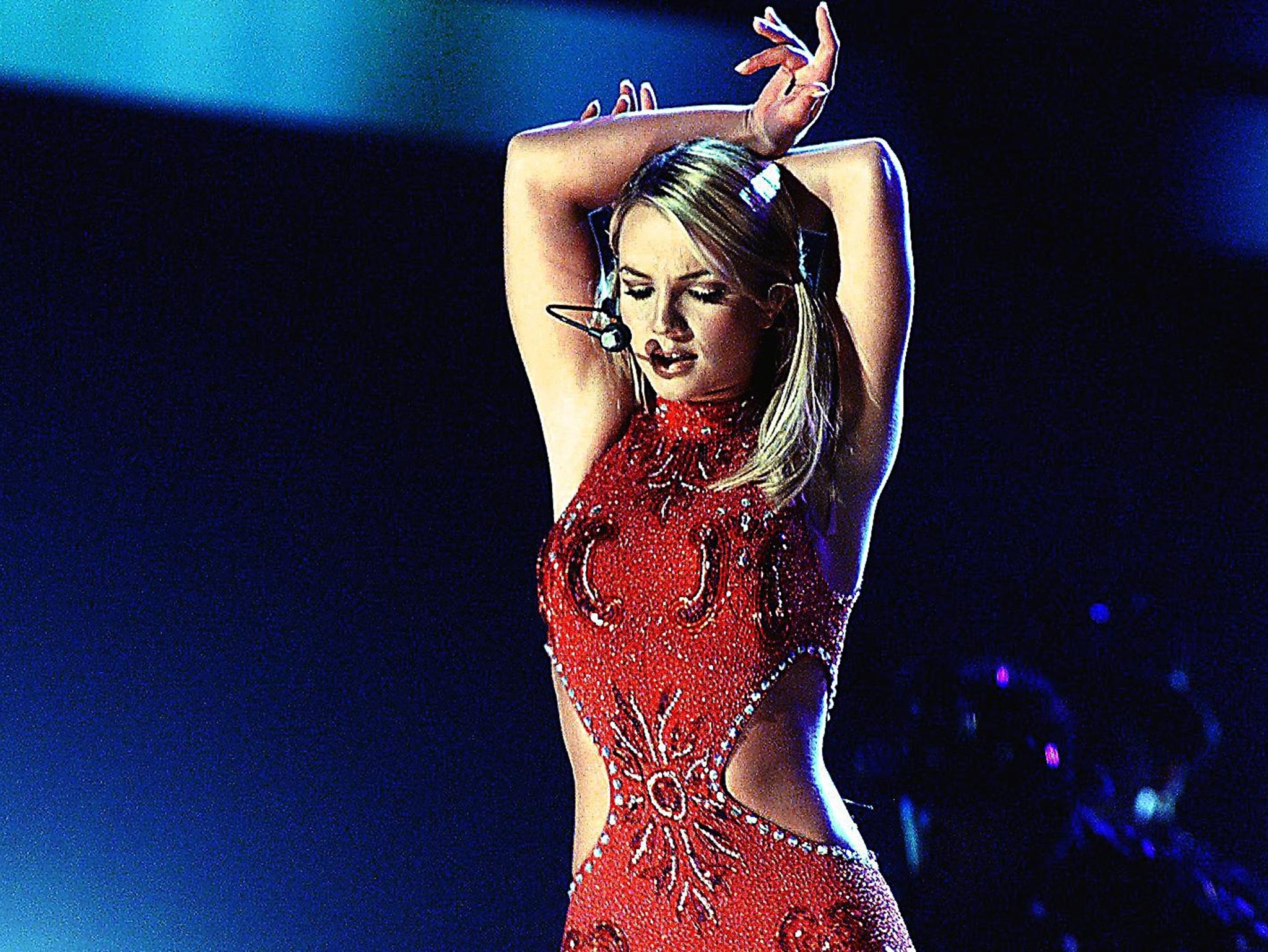

‘I can’t feel my face when I’m with you’ was a ubiquitous pop refrain of summer. The eponymous track by The Weeknd reached number three in Britain and number one in America. But for fans of the once edgy R&B act it may come as a surprise that ICFMFWIWY was written by the same man who penned Britney Spears’s ‘...One More Time’.

Max Martin is among a “mysterious priesthood” of Swedish songwriters who have crafted and controlled the sound of pop music since the early nineties. The mark of Martin, Dennis PoP, Dr Luke and others is so great that in 2014, a quarter of songs in the Billboard 100 were credited to a Swede. One interviewee rightly dubs Dr Luke “The Beatles of our generation”.

It is on this cabal that The Song Machine sets its sights. John Seabrook, staff writer at The New Yorker, spins a tight yarn. Starting from the blueprint-setting ‘All That She Wants’ by Ace of Bass, through the trials and tribulations of the Backstreet Boys – summarily ripped off by their manager Lou Pearlman who had himself down as a sixth member and used the hundreds of millions of dollars they made to prop up a fraudulent business empire that eventually imploded – and the Rihanna and Chris Brown saga up to Taylor Swift’s battle with Spotify, Seabrook delights in telling the story of both a grubby industry and its gilded facade.

Ducking and weaving its way through two and a half decades, one of the The Song Machine’s greatest achievements is to situate the pop song within a shifting matrix of technological evolution, diminishing revenue streams, and warring egos, while only deviating slightly. Seabrook is clever in returning again and again to individual songs – Ne-Yo’s So-Sick, Katy Perry’s Roar - picking them apart to analyse every thwoka thwoka and pish pish. He is a man intent on cracking the genome of the “genre-busting hybrid” that these Swedes have created: “pop music with a rhythmic R&B feel”. This longitudinal and latitudinal study, combined with immense research, makes for an eminently readable book heavy on detail. We learn that the top songwriters aim for a ‘hook’ in their songs every seven seconds. And that the oft-awkward phrasing of the Swedish-penned lyrics is due to English being their writers’ second language. “We are able to treat English very respectless [sic], and just look for the word that sounded [sic] good with the melody,” as one interviewee puts it. ‘Hit me baby one more time’ was intended to be a girl’s plea to a boy to call her again.

Reading The Song Machine, I developed a newfound appreciation of these expertly-crafted three-and-a-half minute mini-masterpieces. Or as Seabrook calls them, “industrial strength products… the bubblegum pop of my preteen years, but… vodka-flavoured and laced with MDMA.” In an interesting analogue-digital interplay, I found myself reaching for my phone and re-listening to these hits with fresh ears and a more open-mind. Seabrook has embraced this - a note at the end of the book explains that he has curated a Spotify playlist for each chapter and hitmaker.

There are a couple of complaints. In focussing on the Swedes, Seabrook selects a decidedly white prism through which to look at pop. Abba are given as the genre’s primary antecedents – while only a few paragraphs are given over to Motown. But for a musical genre based on African-derived beats and rhythm combined with soaring Euro melodies, this is only half the story. An extended chapter on K-pop - the Korean iteration of the Swedish formula - feels extraneous, especially as Michael Jackson, Pharrell Williams (who produced 43 per cent of the music played on US radio in 2003) and Lady Gaga get sideways glances. A tendency to such tangents means that structurally the book does not quite gel.

Had Seabrook subbed out the chapter on K-pop for a more in-depth dealing with the African-American influence on pop music, The Song Machine would have been a near-perfect take on the subject. Despite this, it does still undoubtedly have, as one pop svengali would call it, the x-factor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments