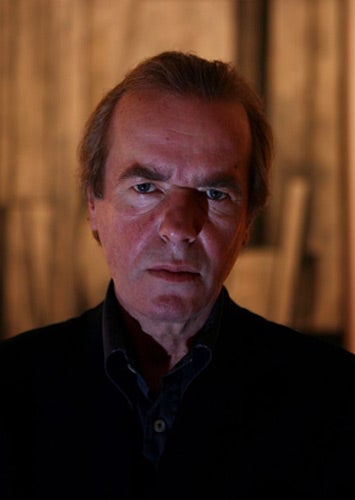

The Second Plane by Martin Amis

Losing a war against cliché

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This collection of essays, articles, book reviews and fiction delineates its author's political trajectory since the destruction of the World Trade Centre in 2001. The opening piece sensitively evokes the horrific aftermath in the Big Apple, while in "The Wrong War", Martin Amis presciently identifies the disastrous centrifugality and "natural ramification of pure power" that was the invasion of Iraq.

His comments on creative writing in "The Voice of the Lonely Crowd" and "Terror and Boredom" suggest an exciting and fruitful professorial sojourn at Manchester University. Amis explores the writer's position with regard to religion and deftly exposes the inner space common to imagistic terrorism and reality TV: "the canonisation of the nobody".

The short stories are masterful and transcendent. "In the Palace of the End", a hallucinatory satire set in a totalitarian state, is transfigured by its insistent humanity. The protagonist in "The Last Days of Muhammad Atta" descends from Camus; Islamism is as much pornographic spectacle as nativist puritanism. In general, the earlier pieces work best, although a review of Ed Husain's The Islamist provides one of the very few beneficent portrayals of Muslim people.

However, the author's comprehension of Islam and Islamism remains inadequate. He tends to discount violence inflicted on the economic periphery, and displays wilful ignorance of history, economics and global politics. From the title onwards, Amis buys into the febrile irrationalism that "9/11 changed the world" and that "our current reality is unforeseeable, so altogether unknowable". These dominant sophistries seem to have displaced the earlier flatus about the "end of history". His worthy identification of "the moral crash" supposedly consequent upon September 2001 conveniently ignores the train-wreck of history, and the systemic amorality of empires and nation states.

Amis rightly criticises the cultish reductiveness of Islamism. In its "intellectual vacuity", this malevolent pantomime is a paradigm of patriarchy, neo-colonial humiliation and big bucks. But for Amis and Islamists, alike, the world has become simple. He follows psy-operators like the historian Bernard Lewis into disinformation, medieval tropes and the High Victorian fixation with sex and camels. Amis correctly accuses Islamists of lacking a sense of temporality, yet he himself displays the identical deficiency: "The West had no views whatever about Islam per se before September 11, 2001". Tell that to Bacon, Burton, Burckhardt, Bin Laden's CIA handlers or, indeed, Bernard Lewis.

Christianity, Islam and Judaism form a syncretic civilisation, yet Amis tiresomely essentialises, as in, "the Muslim male", and seems content to subjugate intellect to atavism: "All religions, unsurprisingly, have their terrorists... We are hearing from Islam." One presumes that this is the tribal, rather than the royal, "we". He iterates a link between Nazism and Islam, yet the Pope was in bed with Hitler and the Holocaust was a millennial culmination of dehumanisation in European Christendom. Bizarrely, Amis seems to think that Israel-in-Bavaria would have faced only lederhosen.

The Axis of Greed has systematically subverted secularism, rationality and economic independence throughout the Oil Belt. The result is militarism and theocratic psychosis. Ignoring this history, in "Iran and the Lords of Time", Amis instead seems energised by pessimism and strategies of tension. Like his irony, his compassion is largely unipolar. Rather than offering a reasoned analysis of war as economic driver, as the book goes on, criticism of US-UK policy is restricted to the uncontentious, the tabloid and the tactical.

Amis implicitly concurs with Mark Steyn's hysterical thesis in America Alone, which boils down to this: "Be very afraid: soon, you will be swamped". Population growth is determined by poverty and female literacy levels. If, in Afghanistan, "the population has increased by 25 per cent" since 2001, it is because of returning refugees, not because of "'genogenesis'". Ultimately, Amis's prose degenerates into propaganda: "the forces of darkness are arrayed against the forces of light".

With occasional exceptions ("his smile... is a rictus, and his eyes are as hard as jewels"), "On the Move with Tony Blair" is fatuous and indulgent. Anti-war protest is depicted as "an incensed but microscopic goblin" while, up close, Bush becomes "generous and affectionate". Embedded with the former PM, our fearless, flak-helmeted author descends on Iraq, just another chorister for the powerful.

In distortions of history, we are informed that the Nazis were "pagans", that the First World War was "made in Berlin" and, in a Borgesian contradiction of his earlier self, that the intention of the Bush administration in invading Iraq was "a dramatic (and largely benign) expansion of American power". The "dame on the Clapham bus" in Cairo, Lahore or Tehran, to whom Amis denies any expression in this book, has greater awareness of the architectures of power and history than soulful literati granted licence to intellectualise visceral bigotries, wrestle with mannequins and indulge in onanistic battle-talk. These writers display so much of what Amis calls "moral unity and will" that their prose tends towards the indistinguishable. "In politics it is surprisingly easy to move from side to side while staying in the same place." Indeed: for the likes of William Shawcross, Christopher Hitchens, David Aaronovitch, Melanie Phillips and now Martin Amis, time's arrow points always towards war.

Global and domestic realities demand a sustained and lucid critique of the intertwined pathologies of Islamism and capitalist war doctrine, and a resolute exploration of alternatives. Far from being morally relativistic, this represents a rational resistance against these ferocious and mutually reinforcing dogmas of guns, butter and God. Unlike novels and drama, life is neither reducible nor dualistic, and Amis does a great disservice by pretending otherwise. It is sad but revealing that such a talented man has abrogated reason and embraced the sirens of destruction. This book is a document of surrender.

Suhayl Saadi's novel 'Psychoraag' is published by Black & White; his 'The Queens of Govan' will be premiered this month by Scottish Opera

Jonathan Cape £12.99 (214pp) £11.69 (free p&p) from 0870 079 8897

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments