The Rich: From Slaves to Superyachts: A 2000 Year History by John Kampfner - book review: The revolution will be slow...

The rich are going nowhere in a hurry. The prospect of yet more protests and riots looms large

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Growing up, I realise I was not really aware of rich people.

In my industrial town in the North of England, there was a handful of families who were regarded as millionaires: the bloke who lived in the big house who made a load from manufacturing paints; his business partner, who had a mini-stately home and trained racehorses; the widow of the bookie; and the local aristocrat who had a proper stately home that was open to the public. That was about it. There were well-off doctors, lawyers, and owners of small firms, but nobody else who would fall into the millionaire category. And we all got along. If there was simmering resentment it passed me by.

Now, in 2014, the rich are everywhere. They’re celebrated and feted, their lifestyles seemingly a constant source of fascination. Where once there was just Alan Whicker and his Whicker’s World on TV, there are whole sections of the media devoted to their stories and their spending. The rich are so ubiquitous that the very wealthiest are called the super-rich. They’re not millionaires any more, but multi-millionaires and billionaires.

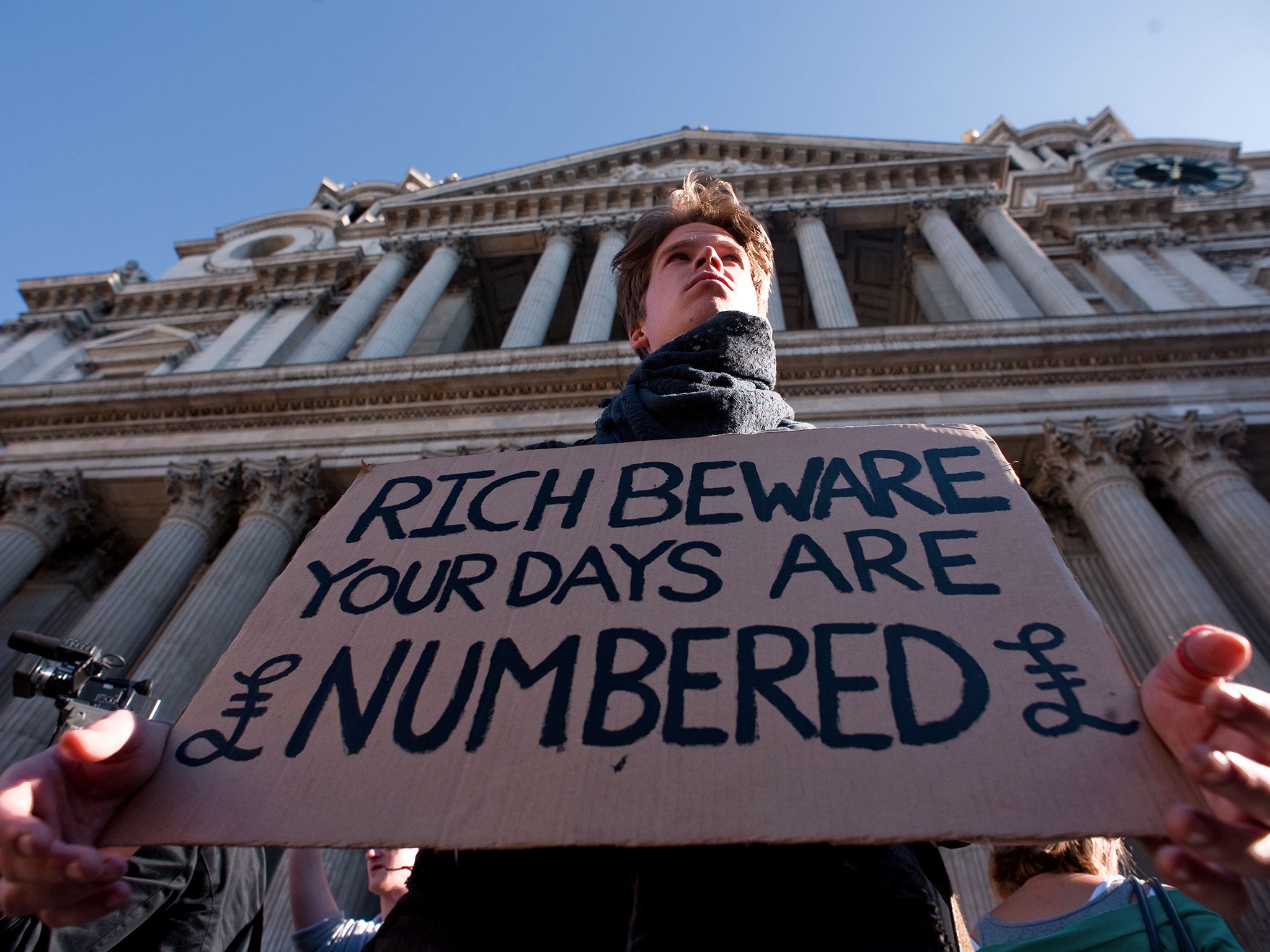

And we don’t get along. There aren’t constant riots in the streets, not yet, but we’ve had demonstrations galore, some of which have ended in violence, where slogans such as “Eat the Rich” have been paraded. So concerned are the wealthy they’ve taken precautions. They live and work in buildings with barriers and CCTV, ride around in cars with blacked-out windows, and in some cases, even have bodyguards.

They’re right to be worried. In 2006, there were 59 protests against social injustice worldwide. In the first six months of last year alone, there were 112. In six years, the rate of large-scale global protests about inequality has grown fourfold. And most of that hostility has arisen in higher income countries. It is, says Robert Shiller, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics, “the most important problem we are facing now, today.”

Yet we are doing precious little about it. Only when the world erupts in flames, it seems, will change occur. That anger at our complacency is the recurring message of a new book, Inequality and the 1%, by Danny Dorling.

To those who care about social imbalance, Dorling, an Oxford University professor, is fast becoming its chronicler du jour. His last work, All That is Solid, laid bare the inequities of the housing crisis. As he points out here, with the help of a familiar battery of arresting statistics, if you’re born in the top one per cent, you’re fortunate – all your life from cradle to grave you will be cared for, you will never have to struggle.

As another Nobel economist, Joseph Stiglitz, said: “In our democracy, one per cent of the people take nearly a quarter of the nation’s income… In terms of wealth rather than income, the top one per cent control 40 per cent … [as a result] the top one per cent have the best houses, the best educations, the best doctors, and the best lifestyles, but there is one thing that money doesn’t seem to have bought: an understanding that their fate is bound up with how the other 99 per cent live. Throughout history, this is something that the top one per cent eventually do learn. Too late.”

Much of Dorling’s frustration is reserved for the UK. We venerate big lottery winners, then stand back and watch, as often happens, their lives implode, and they descend into chaos and addictions. Our favourite TV programme is Downton Abbey that paints a ludicrously romantic picture of the English class system. We claim to loathe bankers, but our laws actually protect them. We even have a Mayor of London (Eton and Oxford) who justified the existence of the one per cent because they supply almost 30 per cent of income tax, and “indeed, the top 0.1 per cent – just 29,000 people – contributes fully 14 per cent of all taxation.”

For Dorling, this paean of praise for “greed is good” from Boris Johnson is the last straw. Rightly, he points out, the rich do not pay tax very willingly and go out of their way to avoid paying when they can, sometimes calling upon far-fetched financial structures to assist them.

Where Dorling struggles, however, is with human nature. It must rankle deeply with him that we are so lackadaisical. Even our response to “greed is good” was telling – and must have enraged him.

In the movie Wall Street, the famous speech by Michael Douglas playing Gordon Gekko was intended as a biting indictment, designed to dissuade anyone from going down the same arch-capitalist road. Instead it was seized upon as a clarion call by an entire generation of wannabe Gekkos.

Part of our failure to tackle the domination of the one per cent is that there is not actually much we can do. Not in a hurry, anyway. The only quick-fix to repairing such a skewed society is to legislate along Stalinist lines, which is clearly not going to occur.

More reasonable is a softly, softly approach of promoting greater social awareness – to encourage the one per cent to give back more, to gradually make our opposition to rampant materialism known. It should be, as Clive James said, to ensure that “Getting rich – and having much more money than you will ever need – will look as pointless as taking bodybuilding too seriously.”

But just how slow this revolution will be – if it occurs at all – is perfectly illustrated by John Kampfner’s The Rich, which covers the 2,000 year history of the super-rich. Kampfner’s vivid account could be a companion piece to Dorling’s diatribe against the one per cent, or vice versa. He adds the colour to Dorling’s charts. To qualify for the one per cent, or more to the point, the 0.1 per cent, you have to be opportunistic, decisive and ruthless. Then, with any luck, you can cement your position, sending your children to the best schools, consolidating their position in the social hierarchy. Writes Kampfner: “New money becomes old money. Dodgy reputation becomes pillar of the establishment.”

The rich are going nowhere in a hurry. The prospect of yet more protests and riots looms large.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments