The Retrospective, By AB Yehoshua, trans. Stuart Schoffman

One of Israel's great voices looks back on a creative career – and on the mingled origins of his nation.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

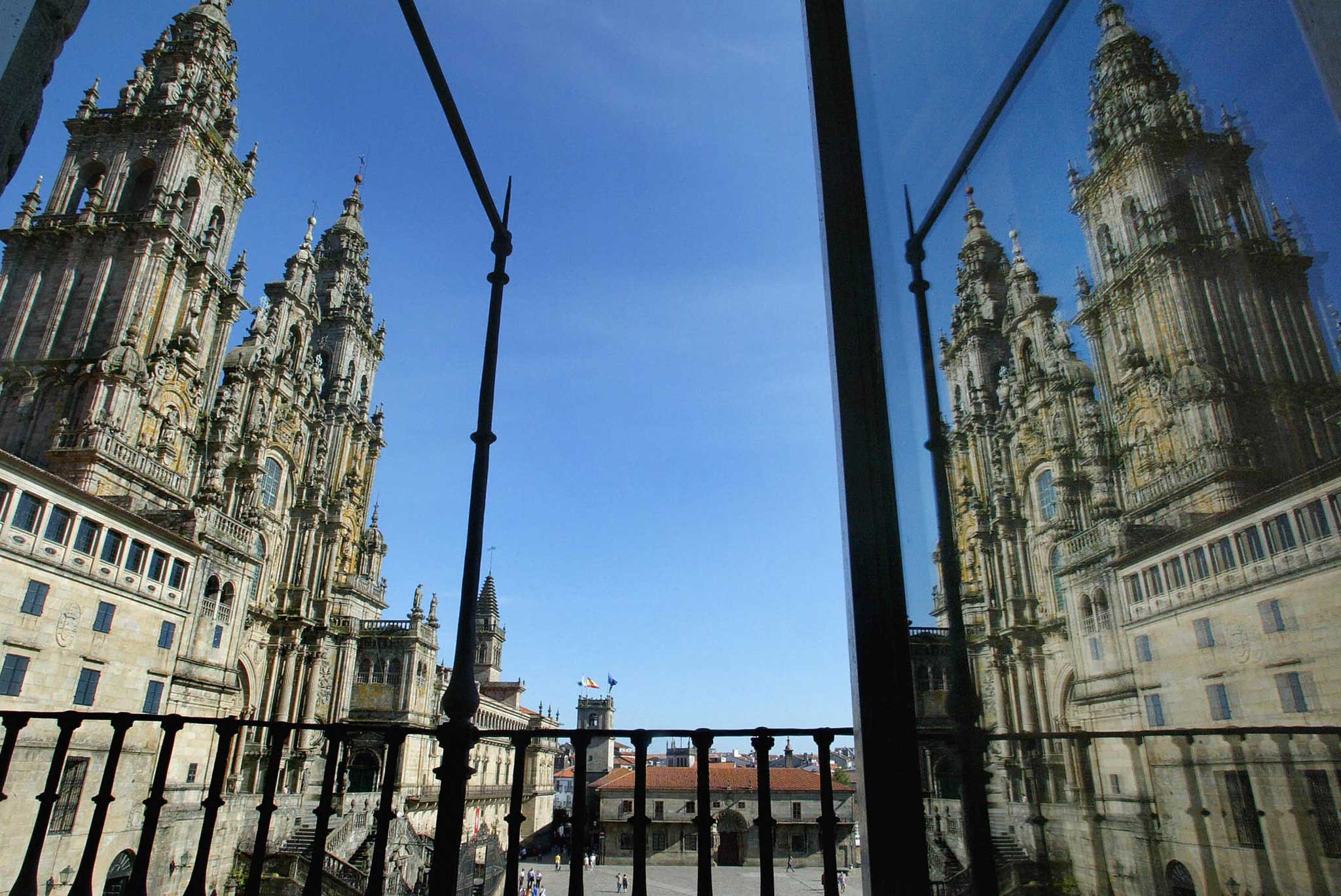

Your support makes all the difference.The eponymous retrospective of Yehoshua's novel is a festival in Spain's Santiago de Compostella devoted to the early work of the Israeli auteur, Yair Moses. Prompted by the local embassy, the venerable director attends. The movies, some all but forgotten by their creator, provoke nostalgia and introspection. In particular they revive memories of the creative dialectic between director and scriptwriter that ended in tears.

Get money off this book at the Independent bookshop

The event which occasioned the divorce is apparently commemorated by a canvas which hangs upon the wall of the director's hotel room. Dating from the Renaissance or thereabouts, the painting features a young woman breast-feeding an elderly man, whose hands are bound behind his back. The right breast is occluded, but the left exposed for the benefit of the viewer.

The image echoes the scene which would have concluded the last picture director and screenwriter made together, had not the former censored it. Called The Refusal, it starred the screenwriter's erstwhile lover, now the director's travelling companion. In the film she plays a feisty soldier recruited by a couple of Holocaust survivors - made barren by their suffering - to bear a child on their behalf. But as birth approaches the girl abrogates the pact, and gives the child up for anonymous adoption.

What Trigano - screenwriter and lover both - wanted her to do next was re-enter the tumultuous street, and express her excess milk into the mouth of a beggar. The actress refused - in real life - and the director seconded her rebellion, creating an unbridged rift between both the lovers and the creative partners. The director moved from art-house to the mainstream, and the scriptwriter retreated into teaching.

At the director's request an expert is summoned to name the artist, and explain the painting's subject. The newcomer identifies the artist as Matthias Meyvogel, and the painting as entitled Caritas Romana. The act of charity depicted concerns Cimon, a prisoner condemned to death by starvation, and his daughter Pero, who resolves to smuggle paternal sustenance into his cell within her own bosom.

It so happens that this novel's original Hebrew title was Hesed Sefardi. The book's excellent translator, Stuart Schoffman, explains that the word "hesed" - compassion or charity - is a fair equivalent of the Latin "caritas". Sefaradi, he adds, means Spanish, but refers also to the Sephardi: Israel's non-Ashkenazi Jews. Trigano is Sephardi, as is - more obviously - Toledano, the cinematographer. In other words, those early films of Yair Moses present a fruitful synthesis of Ashkenazi and Sephardi, with the implication that without the second element something - "hesed" - is lost.

The films provide a scrapbook - both realistic, but more often symbolic - of Israel's earlier and more unburdened years; which is not to say that Yehoshua, or his surrogates, offer any easy absolution for the sins of youth. They also revive more personal memories in the director, though we are advised that Moses has been wary of ever trying psychotherapy, lest his source of inspiration be excised. This disingenuousness is explosively undermined by the novel's controlling image, a prime candidate for Freudian investigation.

Suffice to say that at the book's end Moses finds himself in the reenactment business, as he makes a desperate effort to reconnect with Trigano, and his better self. Yehoshua - one of Israel's greatest voices - despite all odds retains a modicum of optimism. "The inspiration I craved has returned," thinks Yair Moses, "I am drinking it straight into the chambers of my heart, against the reality that strangles us." I look forward to his next movie.

Clive Sinclair's 'True Tales of the Wild West' is published by Picador

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments