The House of the Mosque, By Kader Abdolah trans Susan Massotty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The elders in a prominent Iranian family have always consigned certain belongings to posterity in a hidden crypt underneath their city's mosque, which is now an Ali Baba's cave of clerical turbans, mildewed letters and treasures revealing the secrets of their age, all entombed under centuries of dust.

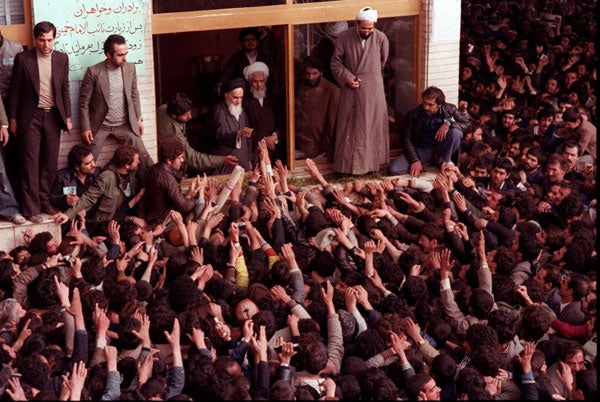

So Aqa Jaan, head of the sprawling household in the pious province of Senejan feels duty bound to record in his journal the stormy events of 1979 - the flight of the Shah, the Islamic revolution and the reign of Ayatollah Khomeini – to preserve in the mosque's crypt. He writes surreptitiously yet incorrigibly, as a living witness in these terrible times. His brother, Nosrat, an irreligious renegade and rake, is also compelled to catalogue events in Tehran, secretly filming the Ayatollah's inner sanctum, knowing the risk this poses on his life.

There is, in these two brothers' desire to explain the great hope, and the great betrayal of the Islamic Revolution, a shadow of the writer Hossein Sadjadi Ghaemmaghami Farahani, who first fought against the dictatorship of the Shah, then the theocracy of the ayatollahs, and wrote all the while for an illegal journal, publishing two books in Iran before fleeing to Holland. Even his penname - Kader Abdolah – made up from the names of two executed friends, bears the scars of the revolution. This latest book, translated from Dutch, has catapulted Abdolah onto Holland's bestseller lists and was recently voted the 'second best ever' Dutch novel, all the more remarkable in a country where issues around Islam have become increasingly sensitised following the murders of prominent critics of immigration, Pim Fortuyn, and the film-maker, Theo Van Gogh.

Unlike various realist accounts of this watershed historical moment that have recently appealed to the West (Azar Nafisi's Reading Lolita in Tehran; Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis) Abdolah's is a semi-mythical narrative (not unlike his previous book, My Father's Notebook) not quite magical realism but bearing a 'flying carpet' element of fantasy: there is a host of anthropomorphic animals - the mosque's knowing cats, a resident crow with Cassandra caws of impending doom, a plague of ants defeated by prayer - and two silver-haired servants known as 'the grandmothers' who appear to have been resurrected from Persian fable. The counterpoint to this enchanting (and unabashedly sentimental) Arabian Nights aspect is the horrifying realities faced by Aqa Jaan's family, which worsen as the revolution progresses. Sons are tortured, daughters married to radical imams, false confessions are secured and informers rewarded.

The myth-making extends to Abdolah's abundant use of spiritual imagery. The novel opens with the same, mystical words that begin the Quran: "alif, laam, mim" (letters of the Arabic alphabet) believed to unlock the mysteries of the universe if correctly decoded. He also translates its verses or 'surahs' creatively, with some elided into others, and in a way that extracts their essence as devotional poems, not unbending edicts. In so doing, he forces a conceptual separation between the reductive, fanatical streak of Islam revealing itself on the streets of Iran, and the open-ended, poetic nature of Quranic verse.

Undercutting religion is an irrepressible eroticism: couples make love atop the holiest corners of a minaret; love poetry is hotly whispered in bedrooms; when Aqa Jaan finds a verse by a progressive Tehrani female poet, he finds her words profane, yet begs his wife to recite them, amorously, to him: "Here are my lips, My neck and burning burning breasts. Here is my soft body!"

Abdolah's juxtapositions - the spiritual and the earthly, myth and reality - give the story a powerful irony. Khomeini is, in 1979, a hero, we are reminded, before he becomes the villain. He offers Iran salvation from the tyrannical whimsies of the Shah. By the end, the freedom fighters are the new tyrants. Abdolah lathers the story with an almost deliberate nostalgia, choosing not to drive recent history into the present day. Instead, he presents just the nascent phases of the revolution and the wide-eyed innocence of those, such as Aqa Jaan, who held such high hopes for all it could have been.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments