The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks; illustrated by Caanan White, book review

Graphic novel vividly recounts the heroics of an African-American unit in the Great War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a clear, cold morning in February 1919, the 369th Infantry regiment – a segregated African-American combat unit – returned to New York from France. The most decorated black soldiers of the First World War, they had served for 191 unbroken days in the trenches, a longer time than any other US troops. And they had done so without conceding a foot of ground to the Germans or losing a man to capture. The valour of the Harlem Hellfighters, as the Germans called them, was uncontestable.

Among their ranks was Henry Johnson, the first American of any colour to win the French Croix de Guerre. Honoured with a victory parade along Fifth Avenue, the Hellfighters were cheered on by a crowd of 250,000. Spectators included New York governor Alfred E Smith, press baron William Randolph Hearst and the plutocrat Henry Clay Frick. From a window on 73rd Street, Mrs Vincent Astor and a group of society ladies could be seen waving.

Yet homecoming was bittersweet. Max Brooks's graphic novel, The Harlem Hellfighters, tells a fictionalised version of the soldiers' story, tracing their journey from callow volunteers to hardened veterans. It also makes clear that members of the regiment faced a battle on two fronts: against the enemy abroad and vicious racial prejudice at home.

Spat at and abused by white soldiers and set up to fail by a military hierarchy that provided them with brooms instead of guns during basic training, the 369th was initially assigned to menial labour duties after shipping to Europe. It was only as the Allies continued to struggle on the Western Front that they were seconded to the French army in which, for the first time, they fought as equals beside white troops.

The turn of the 20th century marked a nadir in race relations in America, with lynchings and segregation at their highest point since the Civil War. In Brooks's telling, the men of the 369th join up hoping to fight with distinction enough to put bigotry behind them. That they accomplish the former without prompting any change in the latter is the governing irony of this book. As Brooks's narrator notes: "It'd be nice if I could that say our parade or even our victories changed the world overnight... The truth is we came home to ignorance, bitterness and… some of the worst racial violence America's ever seen."

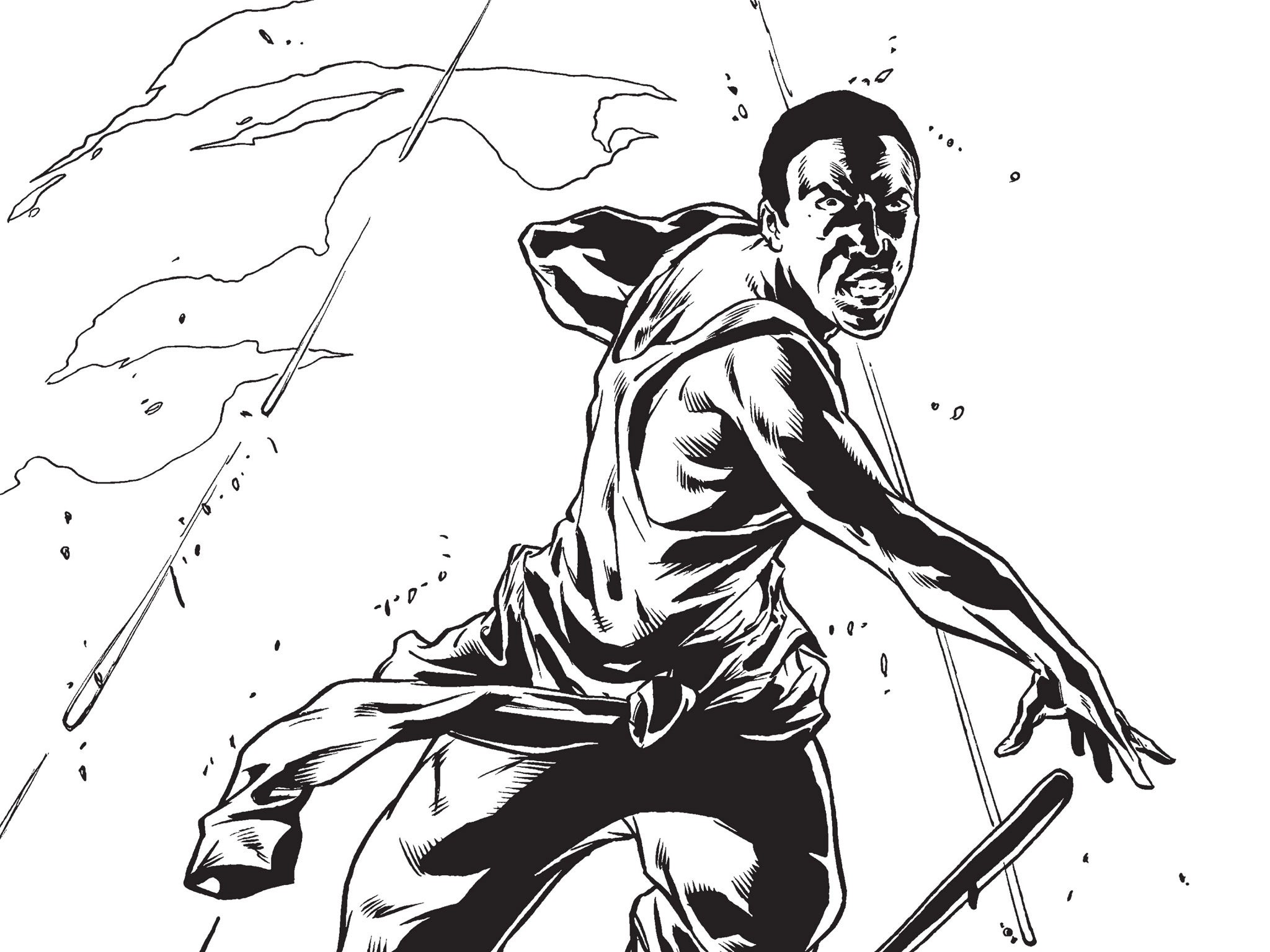

Brooks, author of the bestselling World War Z, conjures the regiment as righteous warriors, raging across Europe and terrifying the Germans with a sublimated fury at their prejudiced treatment. As illustrated by Caanan White, this is a brutally visceral tale. The trenches are the site of bloody and chaotic battles, thick with mud, gore and swarms of rats.

In rendering the unit's story in comic book format, Brooks has found a way to bring their journey to life with an intensity that merges historical events with the momentum of tightly plotted fiction. There are featured roles for real figures such as WEB Du Bois, the great philosopher of race, and James Reese Europe, the regiment's band leader, an acclaimed ragtime composer and conductor who played a major role in popularising jazz on both sides of the Atlantic and was latterly dubbed "the Martin Luther King of jazz".

There are also reminders of the kind of story telling it's only possible to do in graphic form. One especially powerful sequence depicts the fight against improbable odds that won Henry Johnson the Croix de Guerre. On guard duty in the trenches, Johnson fought off a German raid on the regiment despite running out of ammunition. Armed with no more than a bolo knife he killed four of the enemy and wounded 20 more single handedly. Brooks captions White's images with the words of a bigoted white Southern reporter whose double-edged tribute to Johnson says much about the prevailing racial attitudes faced by the Hellfighters: "As a result of what our black soldiers are going through in the war, a word that has been uttered billions of times... is going to have new meaning for all of us... hereafter n-i-g-g-e-r will merely be another way of spelling 'American'."

But the comic strip format has its drawbacks too. The fictional Hellfighters are only sketchily realised. They speak in clunky set phrases ("You got a lot of fight in you Edge. Think you got enough to can the Kaiser?") and as characters, they're straight out of central casting. There's a brooding hero, a well-spoken sidekick with glasses and a bow tie, a big, simple-natured hick from the Caribbean islands, even a grizzled sergeant who puts recruits through hell during boot camp. More than anything, the simplistic dialogue and lurid battle scenes feel like the storyboard for a Hollywood war movie. Little surprise perhaps that Will Smith has already bought the film rights.

Yet Brooks can't be faulted for recognising the potential for the epic in the Hellfighters' tale. The propulsive vigour of his narrative makes for compelling storytelling; an angry, restless testament to the soldiers and their struggles on and off the battlefield. And as Brooks points out in a moving coda, the shadow of injustice still hangs over the Hellfighters. After the homecoming parade, the contribution of the 369th was deliberately overlooked by the US military, with the result that their achievements – or even the presence of African-American fighting units in the First World War – is largely unknown today. That lack of official recognition had consequences.

Henry Johnson, for instance, did not receive a US medal to match his French honours. Neither was he granted disability allowance for the severe injuries he sustained in combat. Physically unable to hold down a job, he died alcoholic and destitute, aged 32. Only in 2003 was he posthumously decorated by the military. Even then Johnson was denied the Medal of Honour, America's highest decoration. His supporters continue to lobby for full recognition of his singular act of bravery. Should they succeed, it feels as though the Hellfighters will have won their last battle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments