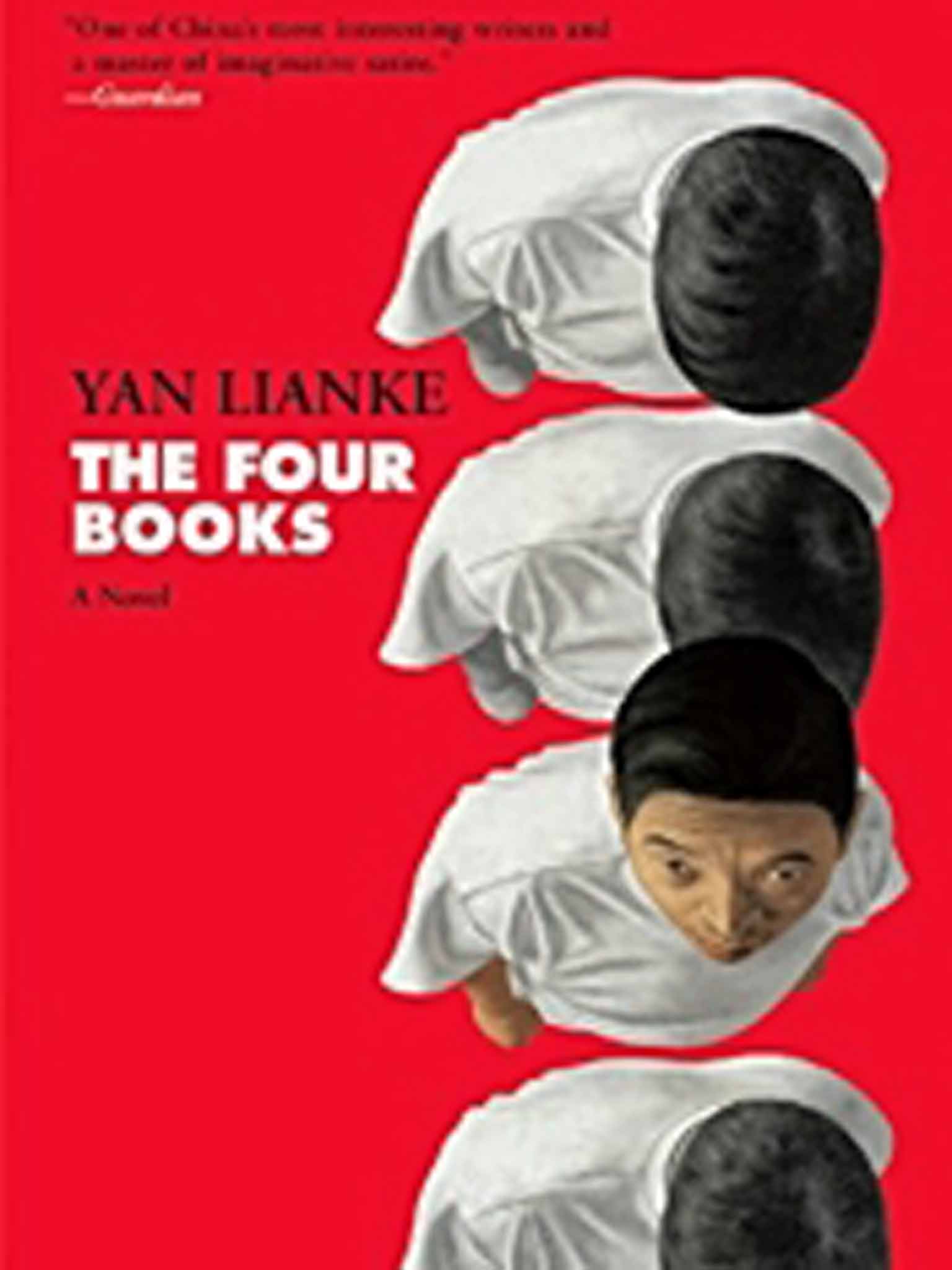

The Four Books by Yan Lianke - book review: Looking back in anger at Mao's Great Leap Forward

Translated by Carlos Rojas, this book is stark, powerful and compelling

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You can tell a lot about a country by how it censors its writers. That Ma Jian's book about the Tiananmen Square massacre, Beijing Coma, was banned, is perhaps no surprise. But a novel about Mao's Great Leap Forward – surely this is something that can be spoken of, over half a century on? Well, no. Or not like this.

Yan Lianke's novel follows his Independent Foreign Fiction Prize-shortlisted Dream of Ding Village, on the blood plasma scandal in 1990s Henan province that led to an Aids epidemic. This is an easier read than that book, no matter that the story is just as grim. The subject is the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s and the terrible famine that followed it, but its more overtly satirical style means it lulls you into thinking you have a clear distance on events, before the reality hits home.

The novel is set in a remote Re-Education district, where a group of disgraced intellectuals are tasked, at first, with growing wheat, and then, when the orders from on high change, smelting steel. That the central characters are named according to their old jobs (Author, Scholar, Musician and so on) keeps us from sympathising too strongly with them, while their leader, the Child, is – literally – a child: serious in his impossible demands, given to tantrums when these aren't obeyed, and simple-mindedly pleased when the "higher-ups" in the provincial seat ruffle his hair, pat his shoulders or award him red silk blossoms or stars.

The novel comes in the form of extracts from four different manuscripts: a central narrative written in a faux-religious register telling the story of the compound, then two works produced in secret by the Author – a set of detailed accounts of the other characters' wrongdoings, which he compiles for the Child, and a private memoir. The final short chapter is a gnomic take on the Sisyphus myth, in which the Scholar imagines God having to vary the rock-roller's punishment as he eventually becomes used to the endless hardship.

Many historical elements of the Great Leap Forward are lampooned, but the laughter is bitter indeed. The Author, claiming he can grow oversized ears of wheat, finds he can only do so by feeding the shoots with his own blood. Naturally, this escalates: "I waited until the next rainy day, then did indeed cut open all ten of my fingers, and stood at the front of the field letting my blood spray over my wheat plants." Stark, powerful and compelling, this book is not "a joy to read", but reading it is certainly a privilege.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments