The Education of a British Protected Child, By Chinua Achebe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

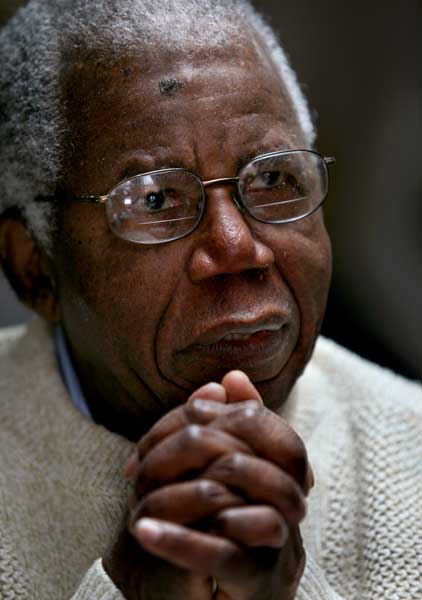

Your support makes all the difference.Chinua Achebe begins this volume of autobiographical essays with a paper written for a lecture at Cambridge University in 1993. He apologises for not being a "clear-cut scholar" because Cambridge turned down his application to study there in 1954. Clearly, it still rankles.

Not that it should: Achebe's career has been cruising at a steady speed into the stratosphere ever since his ground-breaking first novel, Things Fall Apart, was published in 1958. Set in 19th-century Nigeria, it fictionalises the conflict between the pernicious influence of the British colonial power and his own ancient Igbo culture. It is the most lauded novel in Africa's history; Achebe's roll call of honours is a page-turning affair, and he is considered the father of modern African literature.

A dominant theme running through these essays, some of which were first presented more than 20 years ago, is the image of Africa in the world. This is unsurprising because, more than 50 years after Things Fall Apart, Africa is still the object of demeaning misrepresentation. Even today it is sometimes referred to as a country, rather than a continent. No wonder Achebe still feels the need to explain its history, complexity and diversity.

He is also the fiercest critic of Conrad's revered novella set in the Congo, Heart of Darkness. In "Africa's Tarnished Name", Achebe exposes the ridiculousness of some of Conrad's more criminally racist descriptions of African "savages". "This is poisonous writing, in full consonance with the tenets of the slave-inspired tradition of European portrayal of Africa." In "Spelling Our Proper Name" he laments that James Baldwin, whom he met and liked, was "seriously troubled by Africa's lack of achievement".

Another myth Achebe rebuffs with the cutting one-liner, "If you are going to enslave or colonise somebody, you are not going to write a glowing report about him either before or after." He proceeds to describe two different accounts of the city of Benin. The first, written by a Dutch traveller in 1600, compares it to Amsterdam; the second; written 250 years later by the British, describes it as so barbaric that "they had to dispatch a huge army to overwhelm it, banish its king, and loot its royal art gallery for the benefit of the British museum and numerous private art collections".

Early in the book, Achebe states that his thinking occupies the "middle-ground" which is "un-dramatic" and "unspectacular". But don't be fooled; his is a voice that roars.

His essays conflate the personal, anecdotal, political and historical. "What Is Nigeria to Me?" looks back at his relationship to Nigeria, including the Biafran War, and ends up a clarion call for his country's future: "this unruly child". In "Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature", originally published in 1989, he delivers a broadside to the Kenyan novelist Ngugi wa Thiong'o, who was then arguing that African writers should write in their indigenous languages.

Achebe responds with the commonsensical, "I can only speak across two hundred linguistic frontiers to fellow Nigerians in English." Colonialism, Achebe argues, gave him two important things, a lingua franca unifying much of the continent, and an education, although one of his college professors from Britain admitted that, "We may not be able to teach you what you want or even what you need. We can only teach you what we know."

In 1960, the young writer was beginning to enjoy one of a writer's perks – travel. In "Travelling White", he is shocked that Kenya's immigration form asks him to define himself as "European, Asiatic, Arab, Other!" and in Rhodesia he breaks the rules of apartheid by sitting in the front of the bus, telling the conductor, "I come from Nigeria, and there we sit where we like on the bus."

It is in writing about personal relationships that Achebe, a man of his time and culture, falls short. Two essays, "My Dad and Me" and "My Daughters", do not live up to the expectation implied in their titles. There is also considerable overlap between several essays. That said, there is much to admire about the life and mind of one of the world's most important writers and thinkers.

Bernardine Evaristo's latest novel, 'Lara', is published by Bloodaxe

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments