The Dream of the Celt, By Mario Vargas Llosa, trans. Edith Grossman

From saint to traitor, the life of a "gallant gentleman" offers Peru's Nobel laureate a truly grand subject.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.WB Yeats called Roger Casement a "most gallant gentleman". In this extraordinary historical novel, Mario Vargas Llosa peels away Casement's mask to reveal an astonishing, mutating destiny.

Fanatics have always fascinated Vargas Llosa. In The War of the End of the World (1984), it was the mystical, anarchic rebel Conselheiro in Canudos in Brazil. In later novels, these maniacs became the failed, homosexual guerrillero Mayta, the vile Dominican dictator Trujillo, then the self-exiled Gauguin. Bloody-mindedness, ideological dogmatism, a relentless will-to-power, idealism - you name it - lead his dreamers beyond society's norm. Casement was made for Vargas Llosa, and there is a Peruvian connection.

Mario Vargas Llosa came to fame early in 1963 when, aged 27, he won the Premio Biblioteca Breve for La ciudad y los perros (The Time of the Hero). This early novel initiated a remarkably constant fictional outpouring. It revealed how "machismo" is beaten into boys at a military school. They come from all over Peru and its stratified classes and races. The panic was being "different", or worse, a "marica"; the military ensured that effeminacy was defeated.

Vargas Llosa's hallmark from then on, even in erotic and comic veins, was accurate, plain language and dialogue in relation to climate and place, so that you can follow the action on a map. Taken together, his early novels constituted a geographic merging of a fragmented country (desert coast, teeming capital, isolated Andes, jungle). It's only more recently that he has branched beyond Peru and Latin America. So accurate was his first novel that the military symbolically burnt some thousand copies.

Vargas Llosa inherited two traditions. The first was that of concerned, responsible 19th-century realists who wrote earnest novels revealing the hidden, even sordid realities of their cities and lands, from Balzac to Dickens, Galdós and Thomas Mann. The second tradition was more impish and rebellious, close to surrealism and Sartrean existentialism. He teased his readers with narrative tricks or, in his journalism, with outrageous opinions. He was a master at baffling readers' expectations. He has reneged on Sartre and his experimentalism has toned down into supreme control of pace, place, character and plot, rather than submitting his readers to hard work, as it was with La Casa Verde (The Green House) in 1966.

The title of his latest – The Dream of the Celt – refers to an epic poem written by Casement the Irish martyr-traitor, to his nickname and his dream of a free Ireland. But it also hints that onlyfiction can re-imagine such a raw, contradictory life, beyond biography's maybes and history's reasoned, coherent hypotheses. If at the end Casement's fanatic patriotism blinded his lucidity, for most of the novel the Celt's austere, lone struggle against moral corruption remains admirable.

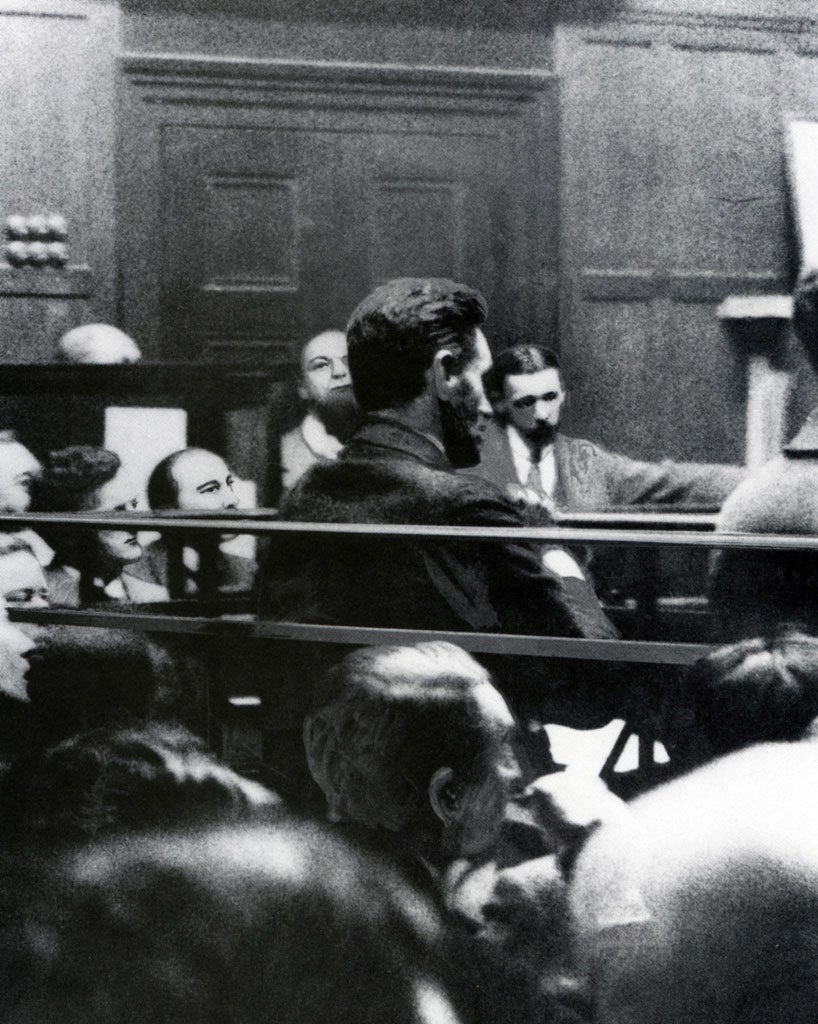

The novel opens and closes in Pentonville prison in 1916. Casement, stripped of his knighthood and humiliated by the leaking of his "Black Diaries", awaits execution for high treason. Interspersed in alternating chapters are flashbacks to his Protestant Irish family, his beloved Catholic mother and recurring dreams about her, his 20 years in Leopold II's Congo fiefdom and one year in the Putumayo Amazon, where he survived the climate, the diseases and the horror to write detailed reports on shocking abuse of rubber workers.

We learn of Casement's Irish revolutionary activities, especially in wartime Germany, and of his failed attempt to prevent the suicidal Easter Uprising. Had he not plotted to enlist the Kaiser's war-machine to help free Ireland from England, Casement would be a human-rights hero.

Vargas Llosa's epigraph from a Uruguayan thinker evokes the astonishing contrasts in all of us. The angel and the demon are inextricably mixed up in his characters. Casement's inner self reflects a personal war with the Congo Free State and then the Peruvian Amazon Company, and the reality behind their propaganda.

Two details represent Casement's detections: the use of the chicote whip made of hippopotamus hide, and the pillory in the Amazonian jungle. Casement tests evidence directly himself, by travel up the Congo and Amazon rivers, as his explorer heroes had done not long before. But he is also at war with his own physical and mental health and with his hidden homosexuality. Casement was a man of action, forced to review his life, awaiting hanging in a timeless prison cell. The novel creates a strange simultaneity, leaving explanations about human motives ungraspable.

Vargas Llosa's ingenious take on Casement's notorious "Black Diaries", released by the British to stall any petition to save his life, tackles the forgery issue by showing that it was partly true and often pure fantasy. We follow furtive encounters with young native men, but also written compensations for any failures. Instinctual, jungle life taught the monkish Casement that he could be an animal. Casement once fell in love with a male Norwegian, but never had sex, and then the Norwegian betrayed him as a British agent.

Beyond Casement's scandalous escapades, the novel questions colonialism's numbing cruelties. Was it just greed for black gold? Or was it original sin, plain human evil? Vargas Llosa's novel measures his characters' mental life with the nightmare of history, as if individual motivation and psychological identity cannot be isolated from baffling historical circumstances.

Inevitably, Joseph Conrad appears in relation to Casement's defence of European values. Here Vargas Llosa enriches the colonialism debates. Conrad admitted that "you've deflowered me Casement", yet refused to sign the petition to save him. Was it a disagreement about colonialism? For Conrad, Africa turned Europeans into barbarians; for Casement, it was Europeans who brought barbarity with them.

Vargas Llosa's literary realism seems so natural, with no lyrical outbursts, no pointless cleverness. His research is meticulous, whether through travel – Iquitos had already appeared in his fiction, but not the Congo, nor Ireland – or through libraries. But it is always embodied in plot and character. Most impressive is how he structures Casement's bifurcating paths, from the voice of conscience to the moving dialogues with the governor in Pentonville and with the Irish historian Alice Stopford Green. The narrator is self-effacing in the best Flaubertian tradition.

Could Vargas Llosa mimic Flaubert and say "Casement, c'est moi"? Is the writer a fanatic who partially identifies with other fanatics? This stimulating biographical novel, written with fiction's best freedoms, refuses to answer such questions. Edith Grossman's translation helps, for the novel seems written in English. Certainly, Casement's fate will touch English-speaking readers more than Spanish ones. Had Vargas Llosa not won the Nobel the month this novel appeared in Spanish, it may have won the prize for him.

Jason Wilson's books include 'The Andes: a cultural history' (Signal)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments