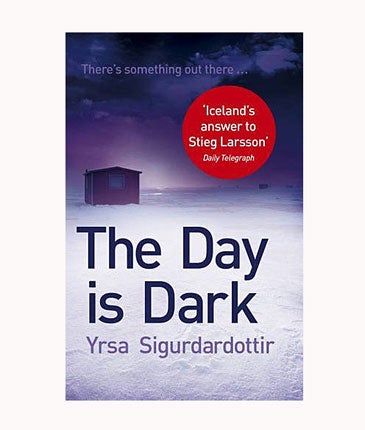

The Day is Dark, By Yrsa Sigurdardottir

A cold case that's worth investigating

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Reykjavik lawyer Thora Gudmunstdottir is offered a special case by her German banker boyfriend. His bank needs an investigation into mysterious happenings in a distant place.

Excitedly planning for the Caribbean, Thora finds herself in furthest Greenland, accompanied by her wondrously incompetent secretary, Bella.

Bella provides some humorous leaven in Yrsa Sigurdardottir's novel (translated by Philip Roughton), which reaches deep into human character. It explores the feelings both of the Inuit population and outsiders. In the geologists' camp where mining possibilities are assessed, only two people are apparently left alive. By the time Thora gets there, they too have vanished. It's impossible to get more employees to work there, the place has such a dark reputation. It is also considered evil among the Inuit.

All agree there is a curse on the place, associated with a strange phenomenon in 1918 when a small Danish colony suddenly disappeared. Is there a scientific explanation, born out of the study of contagious diseases, or a traditional one, based on belief in the malign spirit Tupilak, conjured up through a fetish made of bones? The Arctic is full of man-made toxins: could this be responsible for strange epidemics?

Watching Thora from a distance is the Inuit hunter Igmaq, a despairing man. His son has traded in his hunting rifle for a case of beer, his daughter is dead, and his lead huskywill soon be too weak to fight for his position as head of the pack. Deeply reverential towards his ancestors, he believes that the spirits of those who die childless can haunt the living.

As the scientists probe the physical evidence, Thora goes deep into the complex relationships among an isolated group: bullying, alcoholism, irrational hatreds. The newcomers to the camp feel more and more threatened by the environment: both the physical dangers of the land of ice and snow, and those emanating from hostile locals. But there are no stereotypes. The Inuit are divided among themselves, between those who perceive that the old way of life has gone forever and that mining would bring work and hope, and men such as Igmaq, whose dog symbolises all that was finest about the old way of life. It's another complex case for Thora, liveliest granny on the floes, and deeply satisfying for the warm-toed reader.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments