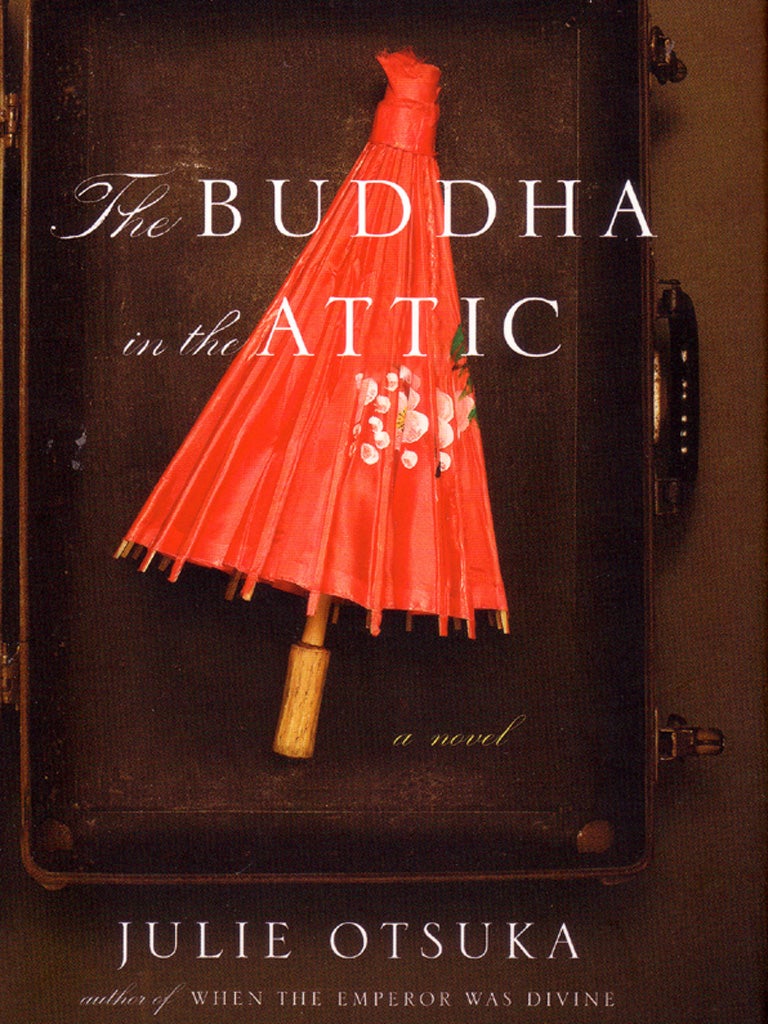

Julie Otsuka's second novel could loosely be described as the prequel to her first, When the Emperor Was Divine, the story of a Japanese-American family interned during the Second World War. Narrated in the first-person plural, The Buddha in the Attic is a slight, but powerfully moving piece of prose. It tells the story of a group of Japanese mail-order brides, from their journey to America, through marriage, work, childbirth and motherhood, until they and their entire communities are rounded up at the beginning of the war.

They crowd on to the boat, "mostly virgins", some as young as 14, each clutching a photograph of their future husband. They dream about their new lives, asking each other "Will it hurt?" The answer is yes – and this is only the beginning.

The men awaiting them bear no resemblance to the handsome young faces in the photographs, and they take their brides "roughly, recklessly". The women are sent to work in the "hot dusty valleys" (worse than the rice paddies) or below stairs in the "big houses" in the suburbs. With their dreams shattered, the women bear children who harbour ambitions of their own – one wants to marry a preacher "so she wouldn't have to pick berries on a Sunday", one wants to go to college "even though no one she knew had ever left the town". Others dream of becoming doctors, teachers, even gangsters.

Otsuka's work challenges the traditional form of the novel in more ways than one. Her story is split into eight sections, each a chapter in these women's lives, and the rhythmic, repetitive flow of collective experience, combined with the sparseness of the descriptions, means her intensely lyrical prose verges on the edge of poetry. Some might find the plurality of voice troubling, suggesting that it does little to restore individual identities to those whom history has forgotten, but I would argue the opposite. A host of individual characters and experiences crystallise as families and communities take root. But all too soon, the only evidence of these lives is the "traces" they leave behind, like the "tiny laughing brass Buddha" hidden "up high, in a corner of the attic, where he is still laughing to this day".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments