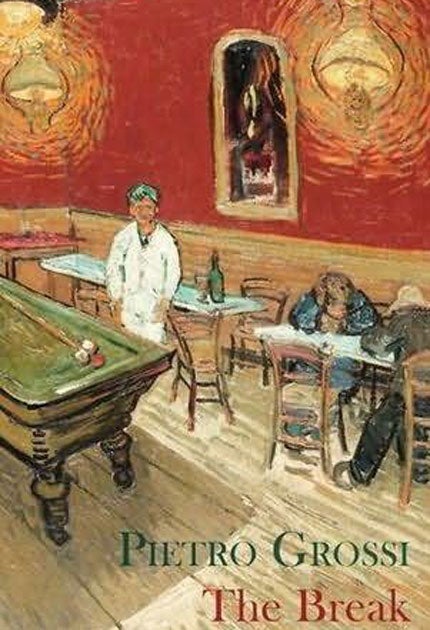

The Break, By Pietro Grossi

Italian bribery and billiards

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Break is small and perfectly formed. This is just as well, since reaching its end leaves the reader desirous to start all over again, and/or furious at its brevity. This is all the more surprising since the subject of the novel is billiards – not one about which I have ever felt passionate. No more have I ever held an interest in boxing, yet I still voted for the young Italian writer Pietro Grossi's Fists to win last year's Premio Campiello. As with his literary inspiration Hemingway's novels on safari hunting and bullfights, the glory is in the writing – here succinctly rendered in Howard Curtis's translation.

As in Fists, style beats content in being spare without being sparse, taut without seeming tight. Both novels are about duels to the death, and each ends in surprising reversals and redefinitions of winning and losing. The Break sees the world through the eyes of Dino, who generally keeps those eyes down to ground level, laying roads. In the detail of using first paving slabs and then tarmac, working alongside the immigrants Saeed and Blondie for an increasingly corrupt chain of municipal officials, Dino gradually apprehends the backhanded way things are done in his provincial town.

Despite his natural reticence, Dino's life becomes increasingly involved. First there is Cirillo, his informal mentor at "Italian billiards", who enters him for a contest and gets Dino his first break. Saeed and Blondie teach Dino more than he ever anticipated about the worlds "out there". Through inertia and poverty, his travels are doomed to happen only in the mind.

Two bombs and the exposure of endemic municipal bribery; one sudden death and an equally unexpected birth: Dino's life becomes far more eventful. Sofia might spend her evenings gazing from their top-floor window to the hills beyond, but Dino keeps his nose to the ground – and keeps it clean – until he is forced to recognise that even the humble must make choices, and that these can have personal and political consequences on a par with the most powerful.

Dino's need to comprehend why a "ball never comes back to the same point" is his quest for his own place in the universe. In it lies the striving to make sense of a senseless and at times insane world, and the wisdom to circumvent questions that have no answers. In short, he discovers that breaking and making can be synonymous.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments