The Boat to Redemption, By Su Tong trans Howard Goldblatt

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Su Tong has the dubious honour of being best known not for his own work but for the film Raise the Red Lantern, adapted from one of his novellas. In fact, he used to joke that he was famous for not winning prizes, but at 46, one of China's more established writers has scooped the world's youngest major prize, The Man Asian Literary Award, with this, his seventh novel.

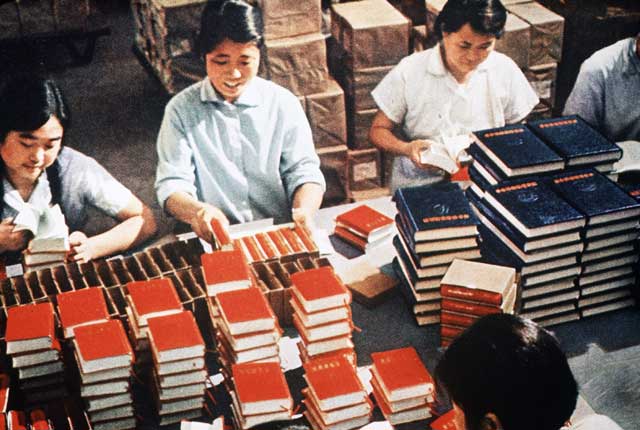

"I don't know if it's a novel that can help overseas readers know more about China," Su Tong has said. "It's just a novel centring on the fate of people caught in an absurd time." Absurd indeed, for The Boat to Redemption returns us to Maoist China, with a set of characters almost completely shorn of political motives and convictions, driven by little more than their immediate wants, sexual needs and desire to rise above the others.

It is almost as if they do not care what the policies are, as long as they can stay on top, and in this, perhaps Su Tong is reflecting modern China. "Buns are made of flour, and that comes from wheat, which is planted by peasants. Our mother's a peasant, so some of this belongs to her," Dongliang is told as his lunch is stolen. The thief "dragged her younger brother over to the wall and used her body as a shield. 'Hurry up!' she demanded. 'Finish it. He won't be able to prove a thing once it's in your stomach.'"

This focus on people rather than politics is perhaps the reason why Su Tong has managed to write for more than twenty years without getting exiled or labelled a dissident, but it also centres his story within the world of the narrator. Young Ku Dongliang's concern is not the Cultural Revolution but his parents' failing marriage and his burgeoning sexuality. The fate of Dongliang's family is dictated by an event that happened before Liberation: a beautiful communist activist is killed and her son lost to the river. His identity is unknown, but when it is known that he had a fish-shaped birthmark, suddenly, everyone in Milltown has a fish-shaped birthmark. "They went crazy that autumn looking for birthmarks on their bodies. At first the craze was limited to males around the age of forty, but it spread to children and then to old men".

In the end Dongliang's father is identified as the martyr's son, and on the strength of his birthmark he rises to become an official in the local Communist Party, where he happily abuses his position with women, long after his marriage to a beautiful political performer who reads the news on the radio, her voice a "musical weathervane". "Her mid-range notes told them that everything was fine, in China and in the world; her lower register told them that news of battleground victories by workers and peasants was pouring in; her alto tones told them that people's lives were like sesame stalks, whose blossoms grow higher and higher."

In a parody of the political movements of the time, an investigation into the father's birthmark declares he is not the son of the martyr after all, but the bastard son of river pirate Feng Four. The family's fortunes plummet. Dongliang takes up almost a gypsy life with the boat people of the Golden Sparrow River, while his father's extra-marital affairs bring tragedy. Life aboard the barge with his father "could hardly be called exile, nor was it some sort of banishment; rather, it was a reclassification." That reclassification dominates the father's life as he struggles for official recognition of his martyr ancestry.

One of his first acts is to cure himself of the sexual adventurism in a way that draws heavily on China's long and mainly underground tradition of erotic and salacious literature: where an inability to control your urges leads to doom. Although his father finds some kind of redemption, Dongliang is just beginning to mature. His comic and un-comic erections increasingly dominate the book in a way more likely to seem unnecessary and juvenile to Western readers. But this is a book that is talking first of all to the Chinese, who are still working out how best to relate to that absurd - and not-so-distant - past.

The first volume in Justin Hill's 'Hastings Trilogy' of novels will appear this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments