The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations that Transform the World, By David Deutsch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Science has never had an advocate quite like David Deutsch. He is a computational physicist on a par with his touchstones Alan Turing and Richard Feynman, and also a philosopher in the line of his greatest hero, Karl Popper. His arguments are so clear that to read him is to experience the thrill of the highest level of discourse available on this planet and to understand it.

Why is Deutsch so different? For a start he has no truck with the powerful tendency in contemporary thought that denies the reality behind the equations of science. Deutsch has no doubt that science reveals the underlying nature of things. He uses a simpler vocabulary than most scientists and philosophers. This is enormously helpful.

For him, science deals in explanations; good explanations. He discusses evolution in nature and notes the similarities and differences between biological and cultural evolution but, crucially, he talks of the difference between animals and humans as a matter of knowledge. Knowledge is information not possessed by the physical world and only to be found in human brains that can act on that world.

For example (and his examples are always graphic and apt): a huge meteorite hit the earth around 65 million years ago and caused climate change and the extinction of the dinosaurs. The natural process of evolution was then the only show on earth - but we have knowledge. We know that such events will occur again but not only are we able to track potential hazards; we possibly have the means to avert disaster, thanks to our knowledge of nuclear fission and rocketry.

Another of Deutsch's key concepts is what he calls reach. True knowledge always has reach. He cites the alphabet. In early systems of written language, a symbol represented a single object; beyond that it had no reach. But an alphabetic language has no difficulty in coining new words all the time.

Even more basic: the different between tallying and mathematics. A tallying system simply counts, making notches on wood or stone. The tallies cannot be manipulated except by lining them up to see which is the largest. At the other extreme, consider the reach of mathematics into the physical world in James Clerk Maxwell's four equations of electromagnetism in the 1860s. They predicted radio waves, from which have flowed not just radio but TV, mobile telephony, radio astronomy, 3G wireless internet, radar and microwave ovens.

Deutsch has plausible answers to some of the greatest mysteries of all time. Why, for instance, are flowers beautiful to us as well as the insects they have evolved to attract? Insects and flowers have the problem of communicating across an evolutionary gap. Within the same species, communication is easy – a single chemical can attract the moth to its mate. But how does a plant signal to an animal?

Flowers employ objective beauty – graded curves, symmetry with subtle variations, colour harmonies. Deutsch points out that individual humans can be as different from each other, in signalling terms, as a plant and an animal. We recognise the universal symbols used by plants because by necessity we use them too. Within less varied species it is different: the hippo is beautiful to its mate but not to us.

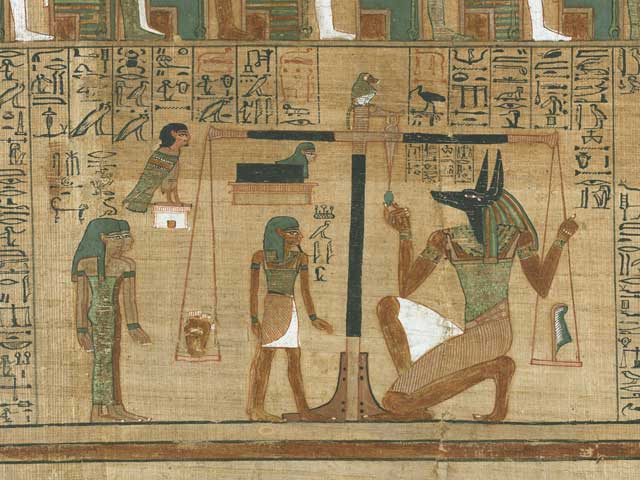

For a physicist, Deutsch's insights into biological evolution are remarkable. Why, when human culture developed with the advent of farming and we began to build permanent well-crafted dwellings, did we not then automatically become rational people? Instead, every society for around the first 9000 years of urban life was obsessed with death cults and barbarous sacrifices. Today we marvel at the Egyptians' fine craft skills, but they employed them in the service of grandiose and hopeless oblations to the afterlife (as shown in the recent Egyptian Book of the Dead exhibition at the British Museum).

Even in Homer, around 3000 years ago, we recognise modernity in the dignity, humour, wiliness, love and loyalty, the fondness for fine clothes and food. But we also still find the incessant bloody sacrifices of animals and the omnipresent louring presence of those supposed gods for whom human beings were merely puppets dangled at their whim.

Deutsch is a child of and a passionate advocate for the European Enlightenment. He shows how and why previous enlightenments – Periclean Athens and the Italian Renaissance – were destroyed, and why the scientific enlightenment that began with Galileo is capable of lasting forever. Deutsch is a modern Voltaire, lacerating fallacious views with crystal-clear thinking.

For him, evolution played a terrible trick on humanity. For most of our history, humankind has not been able to "bear very much reality". In order to prepare us for the great leap forward into true knowledge, to develop our free thinking, problem-solving minds, our brains first had to be honed by slavish adherence to trammelling tribal rituals and death-cult prostrations: a terrible but apparently necessary stage between the gene-led rote behaviour of apes and our modern universality.

For most people, Deutsch's most startling iconoclasm will be his scathing denunciation of contemporary concerns for "sustainability" and the whole notion of Spaceship Earth. He points out that our open society is by definition unsustainable, always becoming something else, but that doesn't mean it is not going to be viable in the future. Quite the reverse. His mantra is "Problems are inevitable; problems can be solved."

Deutsch is the kind of passionate, clear-headed advocate who can change minds. He endorses Stephen Hawking's view that we would be wise to colonise space because the asteroid that will certainly come one day might be beyond even the capacity of our nuclear weapons. I have never believed in space colonisation, thinking it an idle fantasy. With no atmosphere or ecosystem we would have to live in bubbles. But Deutsch convinces me that we could colonise the moon and, after a while, that this life would seem natural.

He points out the shocking fact that the earth's natural ecosystem is almost incapable of supporting human beings, certainly in any numbers. We have created our own life-support system of food, energy, transport, shelter and communications. He is fond of using his own territory of Oxfordshire as an example. Take away the farms and modern infrastructure and, in the woods and downs, little of the vegetation you will find is edible.

Deutsch's overriding concept is universality. Animals have limited repertoires which are genetically programmed and can only be extended by a mutation once in a blue moon. Human beings are universal problem solvers. We can solve problems we don't yet know exist; our language is universal in that it constantly invents new concepts, and our computers are universal machines, capable of performing tasks for which they were not designed. It is this universality that leads Deutsch to conclude that human development will now extend infinitely into the future, even beyond residence on planet earth.

This is the great Life, the Universe and Everything book for our time and the answer is not 42: it is infinity. To understand precisely what Deutsch means by this, you will have to read him. Do so and lose your parochial blinkers forever.

Peter Forbes's 'Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage' (Yale) has won the 2011 Warwick Prize for Writing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments