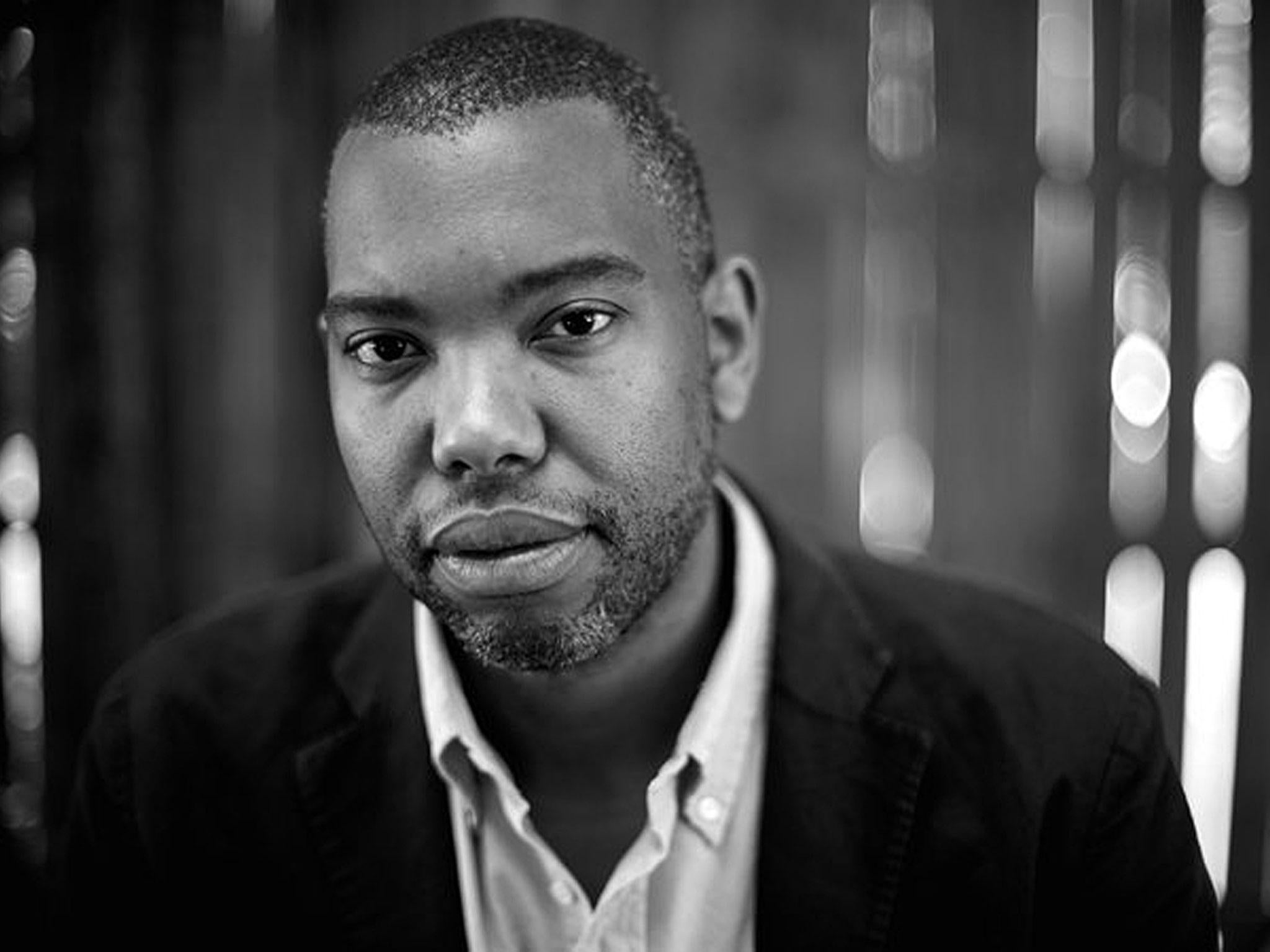

The Beautiful Struggle by Ta-Nehisi Coates, book review: Self-portrait of a protest writer

Celebrated race writer Ta-Nehisi Coates tracks his father's Black Panther days in his first memoir. Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi finds weak spots

The UK publication of Ta-Nehisi Coates' first memoir, The Beautiful Struggle, follows the triumph of his second, Between the World and Me, written in the form of a letter to his young son that became a Number 1 New York Times bestseller last year.

Since that 2015 publication, Coates, a recipient of a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, has been hailed as "the young James Joyce of the hip-hop generation", according to the novelist Walter Mosley, and maybe in recognition of his popular appeal as the Bright New Black Voice of America, Marvel Comics have commissioned him to write a new series of Black Panther comic books. So just how radical is he?

The Beautiful Struggle, published in America in 2008, deals with the struggles of black boyhood, but in a language and bearing a message that is less polished than Between the World and Me. It might, in this rough-hewn state, offer insight into the trajectory that has led Coates to broaden, or indeed, polish his message to gain the widespread acclaim that he has.

The Beautiful Struggle follows Ta-Nehisi and his brother Bill as they navigate the streets of West Baltimore, as they grow up. Young Ta-Nehisi is an awkward and bookish child, afraid to face the streets, until he slowly comes into consciousness, learning about his heritage and identity through a steady stream of books from his father's radical press and from the anti-establishment music of KRS-One and Chuck D's Public Enemy.

The memoir is as much his own as a biography of Paul, his father. Paul is "Conscious Man", a serious and knowledgeable figure who aims to live with self-awareness and integrity. Coates offers a vivid account of Paul's life, particularly his involvement with the Black Panther party. Yet, when Coates tells his own story, characters appear as if through a haze. Their setting, West Baltimore is dark, threatening, represented as if from ten feet away. The book opens with a map, reminiscent of the fantasy board-games of which the young Ta-Nehisi is so fond. The places that feature are given mythical, eerie labels like "The Ruins of Murphy Homes; an unholy den of cut-throats, crooks and ex-cons", and "Lexington Terrace; overrun by the plague of gonorrhea". An arrow out points to "Mecca", that is, Howard University. This is labeled "The way out. The great escape".

This tone continues into the opening scene as a group of threatening youngsters from a neighbouring area approach. "When they caught us down on Charles Street, they were all that I'd heard. They did not wave banners, flash amulets or secret signs. Still, I could feel their awful name advancing out of the lore". In The Beautiful Struggle, we see elements of poetic experimentation that will develop into full-blown lyrical sentimentality in Between The World and Me. Yet, to compare this language (as it has been) to the linguistic breakthroughs of Joyce or James Baldwin would be a mistake; in fact, Coates' language appears carefully curated to offer a fantastical "otherness" to a tough black neighbourhood for the outsider's benefit, while simultaneously offering a camaraderie that allows that outsider to imagine that he or she is being regarded as an insider. This explains, for instance, the contradictory shifts in perspective that at one moment explains that "the djembe is a drum, carved from wood", while at the other confides that "Nigger, he was stacked like Tony Atlas, I'm talking circa '76".

While explaining that his father was promiscuous but at least he was present, Coates says, conspiratorially, "this is a low bar, I know". What must be taken into account, he adds, is that "we lived in an era of chronic welchers, where the disgrace was so broad that niggers actually bragged of running out on kids".

What this sounds like and what Coates ultimately offers is an anthropological exposition of the place he grew up in. A place where "Teen pregnancy was the fashion. Husbands were outties. Fathers were ghosts". There may in fact be some comparison between Coates's voice and the simultaneously patronising and exoticising Indian voices in Salman Rushdie's novels that so enchant some critics.

Coates' notion of progress also appears problematic: it requires a "great escape" out of the ghetto for its happy ending. There is no question that the end might be found inside it . This escape is available to "brothers who try the civilised way" (those who are able study their way out), and ideally it is though a "venerable" school like the elite local one, Poly/Western, that Coates gushes, has carried on the "great traditions" it inherited from its old white neighbourhood. The struggle culminates in an entry into the halls of Howard University. This idea of progress, conservative and unquestioningly in line with neo-liberal capitalism, might help to explain Coates' mainstream success.

Paul Coates' involvement in the Black Panther party becomes a great source of pride for the young Ta-Nehisi: "The cowboy impulse took me first – the thought that I, for all my awkward hands and Krazy-Glued glasses, was rebel blood". His young self compares the Black Panthers to Spiderman and writes: "My new heroes and narrative gave meaning to everything I'd once hated about my life." When the family prepares to move to a six-bedroom house in a quiet suburb, Coates is disappointed, having grown proud of what he calls the danger in his backyard. How does a man who worshipped the Black Panthers as if they were superheroes, and who defined himself through a legacy of black nationalist activism born out of a struggle he had not himself experienced, represent his own struggle?

Maybe the answer can be found in Coates' overwrought lyricism, his easy answers, and his mythologising of a rough West Baltimore neighbourhood. Sixty years ago, Baldwin warned of assigning lofty purposes to popular social protest novels like the anti-slavery Uncle Tom's Cabin, claiming that they were "a mirror of our confusion, dishonesty, panic … They are fantasies, connecting nowhere with reality, sentimental".

It seems with Coates, our consummate modern-day protest writer, similar caution should be exercised.

Verso, £9.99. Order at £9.49 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks