The Age of Nothing by Peter Watson, Book of the Week

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

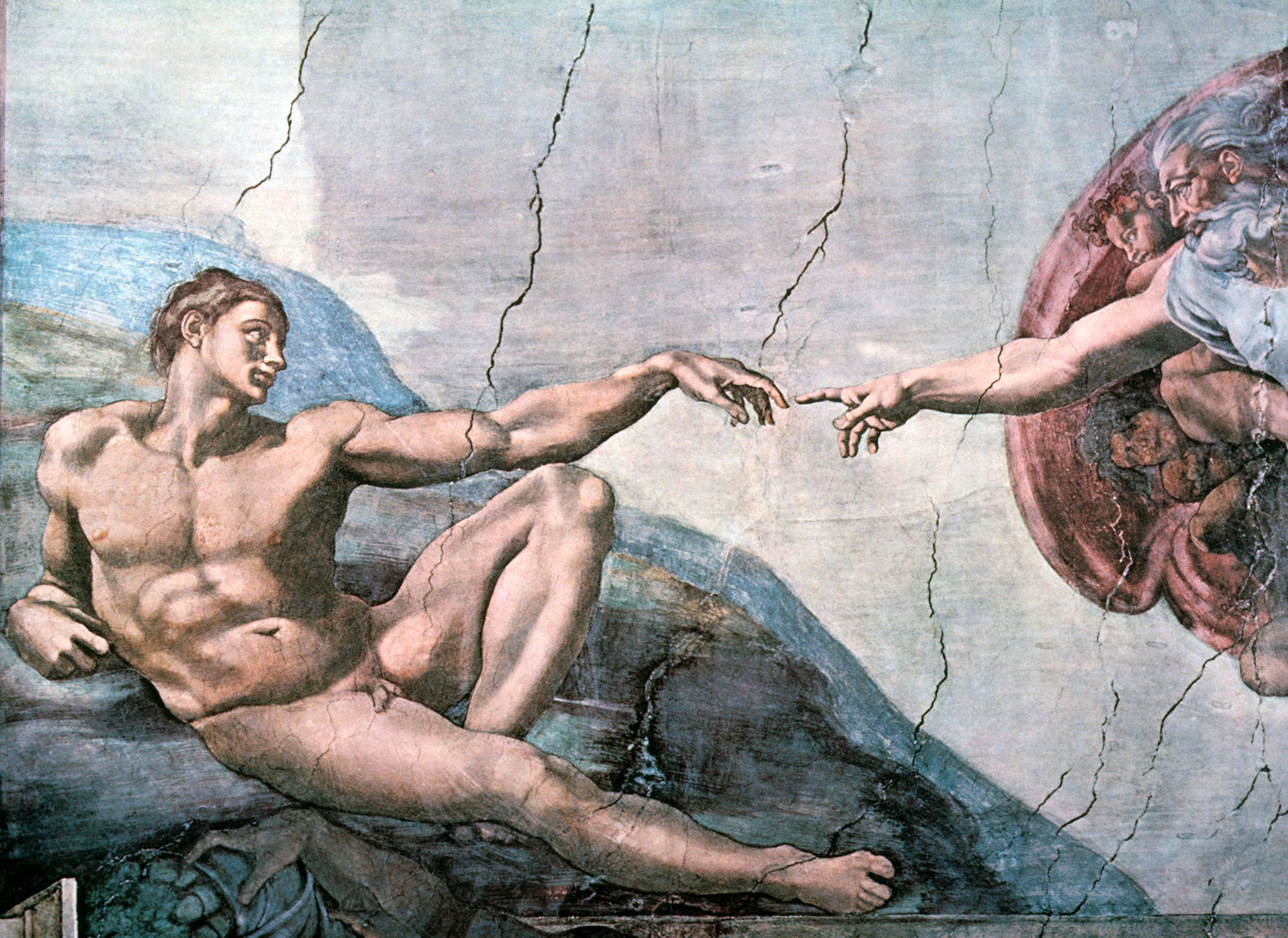

Your support makes all the difference.Peter Watson has written an intriguing and challenging book, which surveys the response of modern Western societies and their intellectuals to the decline of religion. To introduce the reader to the main currents of post-religious thinking, from Nietzsche, who started it with a bang, to Rorty, who tried to end it with a whimper, is no mean achievement.

Hardly an important school of thought is missing: all the ‘isms’ that have contended for attention during the 20th century are there, and Watson’s interest in what they have to say is unflagging. I recommend this book to anyone who needs to know what the loss of religious faith has meant to the high culture of our civilisation and what, if anything, we might do about it.

Nietzsche wrote Thus Spake Zarathustra in the early 1880s, but it was only after the philosopher’s death at the end of the century that its influence began to be felt. By the time of the First World War, Zarathustra had become the most popular work of philosophy in Germany, the book most frequently carried into the trenches by literate soldiers, and one printed for distribution to the German troops in a special durable edition of 150,000 copies. Today Nietzsche is at the heart of the university curriculum in the humanities, not simply on account of Zarathustra’s slogan that God is dead, but more importantly because of Nietzsche’s view that ‘there are no truths, only interpretations’.

With the death of God, Nietzsche thought, comes the loss of the objective world: all that remains is our own perspective, and we must make of it what we can. From this it was a small step to the philosophy of the Superman, who would spend life expressing his ‘will to power’, through weight-lifting, rudeness and – who knows? – the occasional life-affirming murder.

Watson has a lot of time for Nietzsche, while acknowledging that his influence is due more to his gifts as a writer than his capacity for argument. He moves on through the whole range of literature in French, German and English, taking in the post-impressionist and modernist painters along the way, and discovering in all those whom he discusses some interesting and idiosyncratic reaction to the news of God’s death. The range of Watson’s knowledge is amazing. There are things missing that might have been there, of course: music is conspicuously absent, which is a pity, since it was Wagner and not Nietzsche who first made the death of God central to the understanding of our condition, and it was the modernist composers – Schoenberg and Stravinsky in particular – who tried hardest to breathe life into the corpse. But there is a limit to what you can expect from a book like this, which covers a whole century of intellectual endeavour as lightly as it can.

The loss of God has been experienced in many ways: as a challenge to place humanity on the empty pedestal from which God had fallen; as a call to give up on the grand narratives and rest content with our nothingness; as an invitation to therapy, drug-taking, artistic exhibitionism or some other way of making the Self into the centre of attention. All those come under Watson’s eager microscope. In the end, however, he concludes that there is only one available stand-in for God and that is the intense moments of experience. Many writers have touched on these moments, presenting epiphanies in which the world is replete with a meaning that needs no God to explain it. That, Watson implies in his somewhat rambling conclusion, is all that we have.

The sacred moment is described in many ways and with many artistic embellishments. In Rilke it is an exchange of kisses between the earth and the observing consciousness; in Virginia Woolf it is a long sweet languish in a bubble bath of refined susceptibilities; in Lawrence and Nietzsche it is a Dionysiac encounter with life; in Proust it is a door into a space where the unseen eyes of Mother keep their unceasing vigil. And all those accounts are intriguing and suggestive. But they describe experiences that somehow fall short of what we are looking for, and Watson never really tells us why.

According to Watson the most important influence in shaping this search for the sacred moment was not Nietzsche or Proust but Husserl, the founding father of phenomenology. Husserl is widely referred to, but not widely read, since he wrote in an inspissated jargon that doesn’t translate easily out of German, or into it for that matter. But Watson is right to acknowledge him, since he was part of a highly influential movement of thought in the late Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Husserl turned the attention of philosophy towards the structure of consciousness. He held that the concrete, contingent and immediate experience has precedence over the abstract generalities of science, since experience is the reality against which theories are tested. This idea was given literary form by Robert Musil and Karl Kraus; it was given philosophical form by Martin Heidegger, who should be credited with the extraordinary achievement of writing worse than Husserl. And the sections on Musil and Heidegger are among Watson’s best.

However, the God-hungry atheism of the mid-twentieth century has a slightly quaint air today. The life-cult of D.H. Lawrence, the socialist progressivism of H.G. Wells, the naïve optimism of John Dewey, the existentialist nihilism of Heidegger and Sartre – all such religion substitutes have lost their appeal, and we find ourselves, perhaps for the first time, with a gloves-off encounter between the evangelical atheists, who tell us that religious belief is both nonsensical and wicked, and the defenders of intelligent design, who look around for the scraps that the Almighty left behind from his long picnic among us. What do we make of this new controversy? Watson gives a well-informed account of it, but he has no comfort to offer, other than those moments of meaning into which we stare and from which the face of God has vanished.

Or has it?

Roger Scruton’s The Soul of the World will be published by Princeton University Press in April.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments