Thank You for this Moment by Valerie Trierweiler, book review: A long and painful break-up letter

It is impossible not to feel desperately sorry for France's former First Lady

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

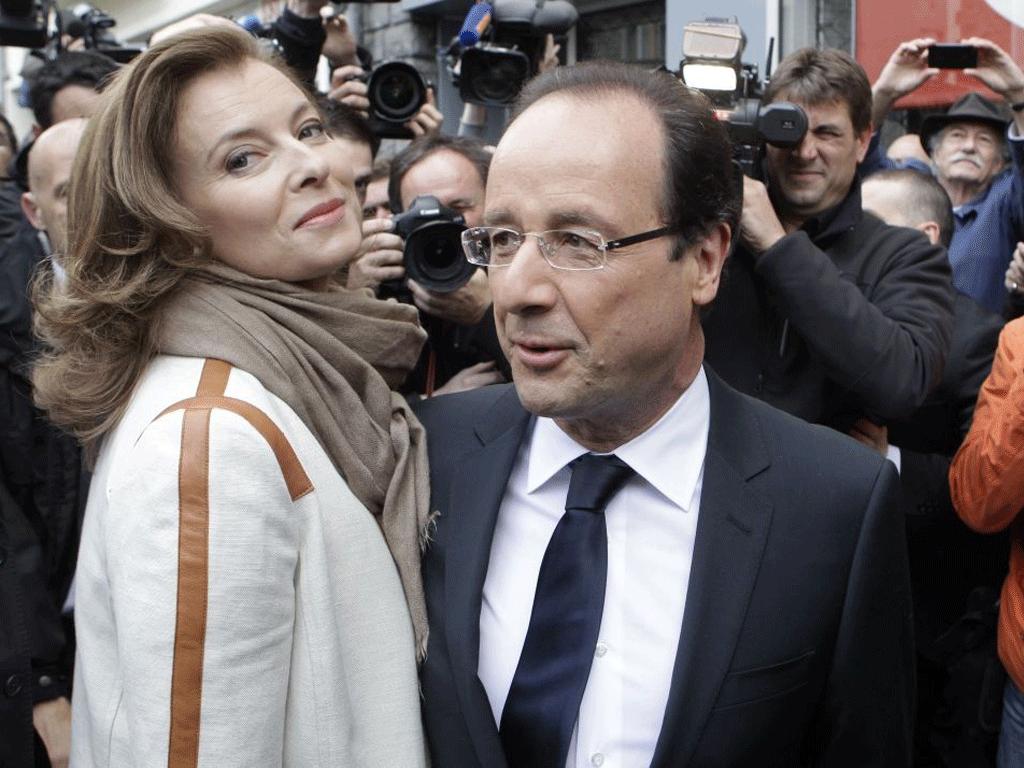

Your support makes all the difference.Why should we have sympathy for Valérie Trierweiler? This is the question that hangs in the air as you start to read Thank You For This Moment, the former First Lady of France’s memoir of how President François Hollande cheated on her with the actress Julie Gayet.

Trierweiler herself was Hollande’s mistress before he became president, the other woman to Ségolène Royal. It is easy, reading this book in Britain, to simply shrug at this ménage à quatre: isn’t this what the French – particularly French presidents – do all the time? And if Trierweiler knew the hurt she caused Royal, why does she deserve our pity now?

But, reading the nearly 300-page memoir, the newly-published English version of Merci Pour Ce Moment that stunned France when it was released in the summer, it is impossible not to feel desperately sorry for Trierweiler. This is, of course, just one version of events, but, given the president has not challenged it, we should assume it to be accurate. She is not only betrayed by the president but lied to, over a number of years, by him. When she needs his support most, he is cold and indifferent. Her much-publicised admission to hospital after taking too many sleeping pills when the affair broke in January is laid bare in new, raw detail: Trierweiler’s mobile phone is confiscated and she is heavily sedated – on the orders of Hollande, she claims, presumably to stop her speaking out.

As First Lady, she was muted by protocol, now she is silenced more brutally by tranquillisers. On an earlier occasion, in 2013, when Gayet fails to deny on TV that she is seeing Hollande, Trierweiler comes close to overdosing on sleeping pills. Yet rather than call for a doctor, Hollande lies Trierweiler down on the sofa of their Élysée apartment, in total silence, not uttering a word of love or care, and slips away – leaving his partner in a semi-conscious state.

Silence is a recurring theme in their relationship. Formerly a political journalist for Paris Match, when Hollande becomes president in 2012, Trierweiler must give up her role to review books for the magazine instead. She can no longer appear on television. She is then vilified by the media and the new president’s circle for tweeting good luck to a political rival of Royal (because Hollande is trying to get his ex-wife appointed to a top parliamentary job, an act of cronyism which disgusts Trierweiler) and so for the next two years the First Lady must remain silent in public. As she says: “The First Lady has no right to speak in public or defend herself.” And yet: “The spouses of heads of state are almost always suspected of meddling in their husbands’ affairs, to have ambition for two, and to unduly spend public money.” Her role as First Lady was one that was “both a beautiful and poisoned gift”.

Trierweiler is speaking not only for herself but for political wives across the globe: Cherie Blair was attacked for having an opinion, Samantha Cameron is praised for keeping quiet. The First Lady in the United States is a higher profile role but it comes with a burden: when Hillary Clinton’s intelligence was on display while her husband was president, it was too much for some; Michelle Obama is routinely cast as a Lady Macbeth figure.

When Bill Clinton’s liaison with Monica Lewinsky was exposed, Hillary Clinton stood by her husband. Trierweiler initially wants to stand by her man too, but Hollande seems desperate for it to be over. Yet as soon as Trierweiler starts to write her memoir, in spring of this year, Hollande begs for forgiveness and offers marriage proposals (something he never did when they were together). Given that, when she was the French president’s partner she continuously doubted her own legitimacy as First Lady (one book about her was titled The King’s Mistress), Trierweiler could be forgiven, perhaps, if she had accepted his proposal this summer. It is a relief, then, when she rejects him: “I have been freed of the chains of protocol, as I have been freed of the chains of that passion. Day after day, I emerge from the prison without chains or bars of being madly in love.”

A woman wronged by a powerful man is one of the oldest stories there is, yet it is one that is rarely told by one of the main players. It is easy to forget, and all the more extraordinary, that Hollande is still president of France as his betrayal is laid bare.

Of the many wrongs put right is the assumption that a philandering French president is normal, acceptable behaviour. Trierweiler refers to him in the third person all the way through her book, until the last page when she addresses him directly. It is then that it becomes clear this is a long and painful break-up letter – told without chapters, just a continuous outpouring of sorrow. As she says, the book is “a message in a bottle – in it lies my past with him”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments