Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain, book review: Republished memoir of Great War remains an evocative account

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.History is written by the victors, claims one school of thought. In this light, the interpretation of the events of the First World War becomes an intellectual and political struggle, narratives being forged from disputing points of view. Questions of authority necessarily arise. Who has the right to testify? To write the official accounts? To interpret the mortality statistics?

The stories of the dispossessed, the vanquished, the silenced, may arise long after the official histories have been published. They surface like angry ghosts, haunting cool libraries. Disrupting the smooth surfaces of official accounts, they cause trouble, like poltergeists. They may be transformed into works of art such as novels and poems, become canonical, and then in their turn be wrestled with, displaced.

Vera Brittain's memoir of her involvement in the Great War was first published in 1933, to considerable acclaim. What do we make of it nowadays? I first read it in the 1970s, when Carmen Calil re-issued it as a Virago Classic, and was awed by its righteous anger. Re-reading it now, I notice more the way it hints at Brittain's conflicts and contradictions about establishment ideals of soldierly self-sacrifice in the name of patriotism.

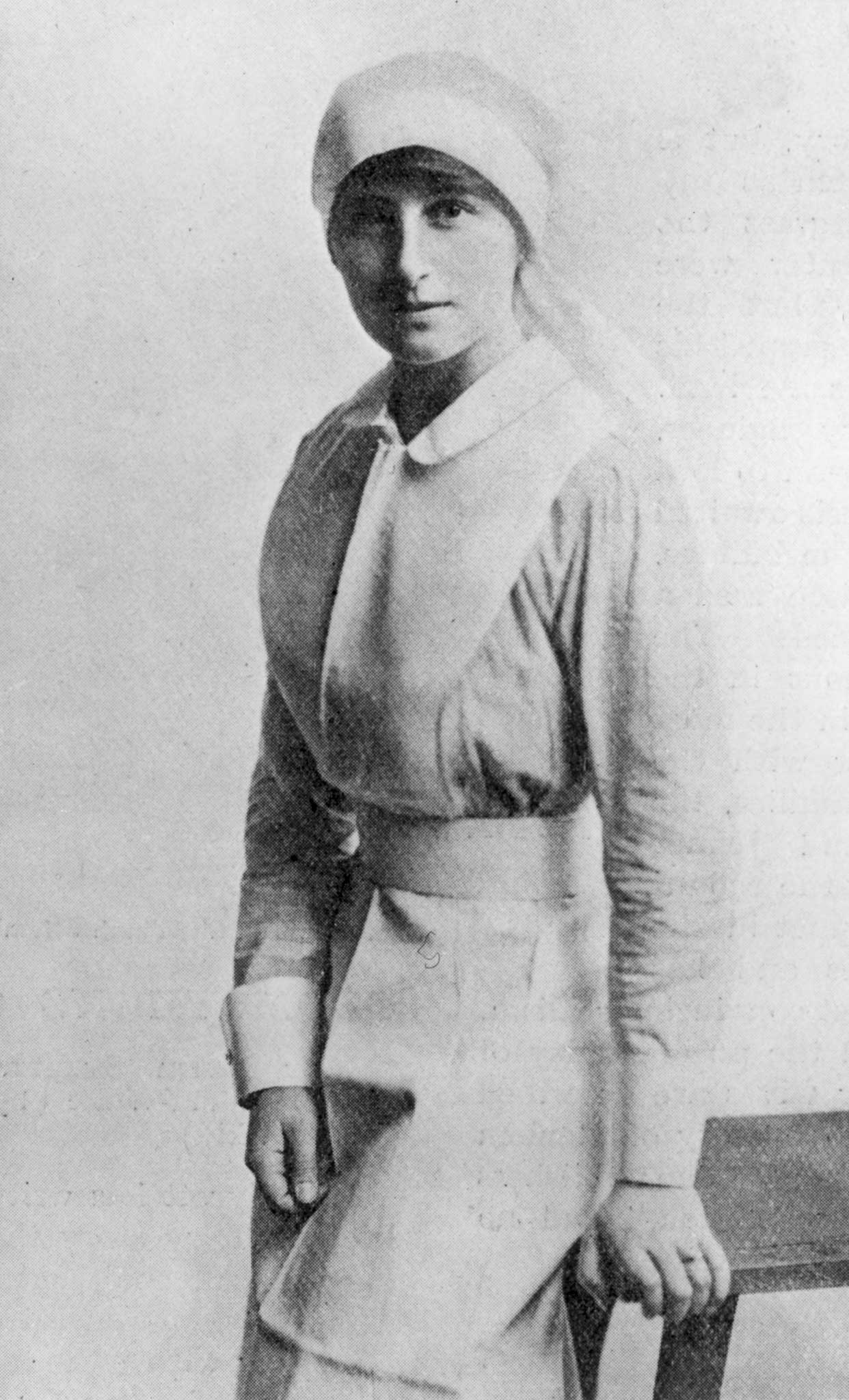

As a Red Cross VAD nurse working in England, Malta and France, she faced her patients' agonising suffering close up. At the same time she recognised, shockingly, how much women wanted to play a part in things, how women lusted for action and power beyond the domestic sphere. Robert Graves, in his own war memoir, Goodbye to All That (1929), describes women handing out white feathers to young men suspected of being malingerers. Today, we despise those women, as Graves did. Brittain seems to have understood that they probably wanted to go and fight. Baulked in that ambition, they turned nasty.

In this anniversary year Brittain's book returns in hardback, complete with red poppy on the front, a helpful introduction by Mark Bostridge, Brittain's biographer, and a foreword by her daughter, Dame Shirley Williams. The red poppy alerts the modern reader to remembrance, certainly, but also to associated problems. What exactly are we remembering? Can we bear to remember certain things? What might we prefer to forget?

Trauma exists outside time and beyond words. Brittain's memoir pulls it back down into language and narrative. Hers is not, of course, the only testament to nurses' work among the stinks and screams of carnage. The excellent anthology No Man's Land – Writings from a World at War, edited by Pete Ayrton, showcases powerful writing by several of Brittain's female contemporaries similarly engaged in bloody mopping-up.

Brittain helped to pioneer the feminist approach that explores how the apparently personal is also deeply political. The "private" losses of her lover Ronald, her brother Edward, and her friends Victor and Geoffrey, forced her to question public attitudes towards the war, and an education system that preached duty, service, honour, heroism and glorious death on the battlefield. Her book, heavy with hindsight, repeatedly mourns the loss of life and youth, utters over and over the sad, bitter refrain "our condemned generation". As it tracks Brittain's political awakening alongside her sexual one, it shows her maturing into a pacifist who supported the founding of the League of Nations. She championed both causes through her post-war journalism and public speaking. The front cover of this reissue should display a white poppy as well as a red one.

Rebellion, like charity, began at home. Brittain was brought up in stifling middle-class conformity in Macclesfield. Clothes symbolised this oppressiveness. Female underwear, a kind of chastity belt, involved "woollen combinations, black cashmere stockings, 'liberty' bodice, dark stockinette knickers, flannel petticoat and often, in addition, a long-sleeved, high-necked, woollen 'spencer'. At school, on top of this conglomeration of drapery, we wore green flannel blouses in the winter and white flannel blouses in summer, with long navy-blue skirts."

Spiritual bulk was added in the form of parental lectures on correct feminine behaviour: the practice of hypocrisy and sexual ignorance as preparation for marriage. Brittain fought her way out, arguing passionately with her parents, supplementing her limited education with voracious reading, becoming interested in the women's suffrage movement, and claiming her right to attend university.

Looking back at her earnest, idealistic, ambitious adolescent self, Brittain deprecates her priggishness and arrogance, but they were her only weapons. She triumphed. She got into Oxford, where a few women were condescendingly allowed by the male authorities to study but not to take degrees, and spent a year reading English at Somerville. When war came, she left her studies in order to train at an army hospital in Camberwell in south-east London and quickly familiarised herself with arduous working conditions, filth and cockroaches, exhaustion, gangrenous wounds and frequent death.

Detailing these physical experiences, she writes succinctly and brilliantly. However, when she records her chaste relationship with her adored Ronald, her style becomes longwinded, turgid, clotted with abstraction, the language itself demonstrating the repression forced on the ardent young lovers, their physical desires buried under the linguistic equivalent of layers of flannel petticoats. This makes her memoir, paradoxically, come even more alive. Following its zigzag between sentimental pomposity and heartbreaking simplicity, we witness the struggles involved in writing it; between remembering and forgetting. The book, like a scarred body, bears the marks of its history. In this sense, it is proto-modernist, showing the process of its making as well as composing a dramatic story.

At first, devotion to Ronald sustained Brittain: every war-torn body she tended represented his. The nurses had to conceal their horror and compassion under carapaces of efficiency, or they could not have survived. One of the photographs illustrating the book shows an operating theatre at Étaples, where Brittain served, the floor pooled with blood, cluttered with a debris of instruments and what look like severed limbs. Men such as Ronald carried into such places were released from their screaming agony with massive shots of morphia. Brittain's book, witnessing such pain, both flinches and is unflinching.

Michèle Roberts' latest novel, 'Ignorance', is out in paperback (Bloomsbury)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments