John Lahr on his dazzling biography of Tennessee Williams

The fabled theatre critic has written an insightful biography of the playwright. Paul Taylor meets him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

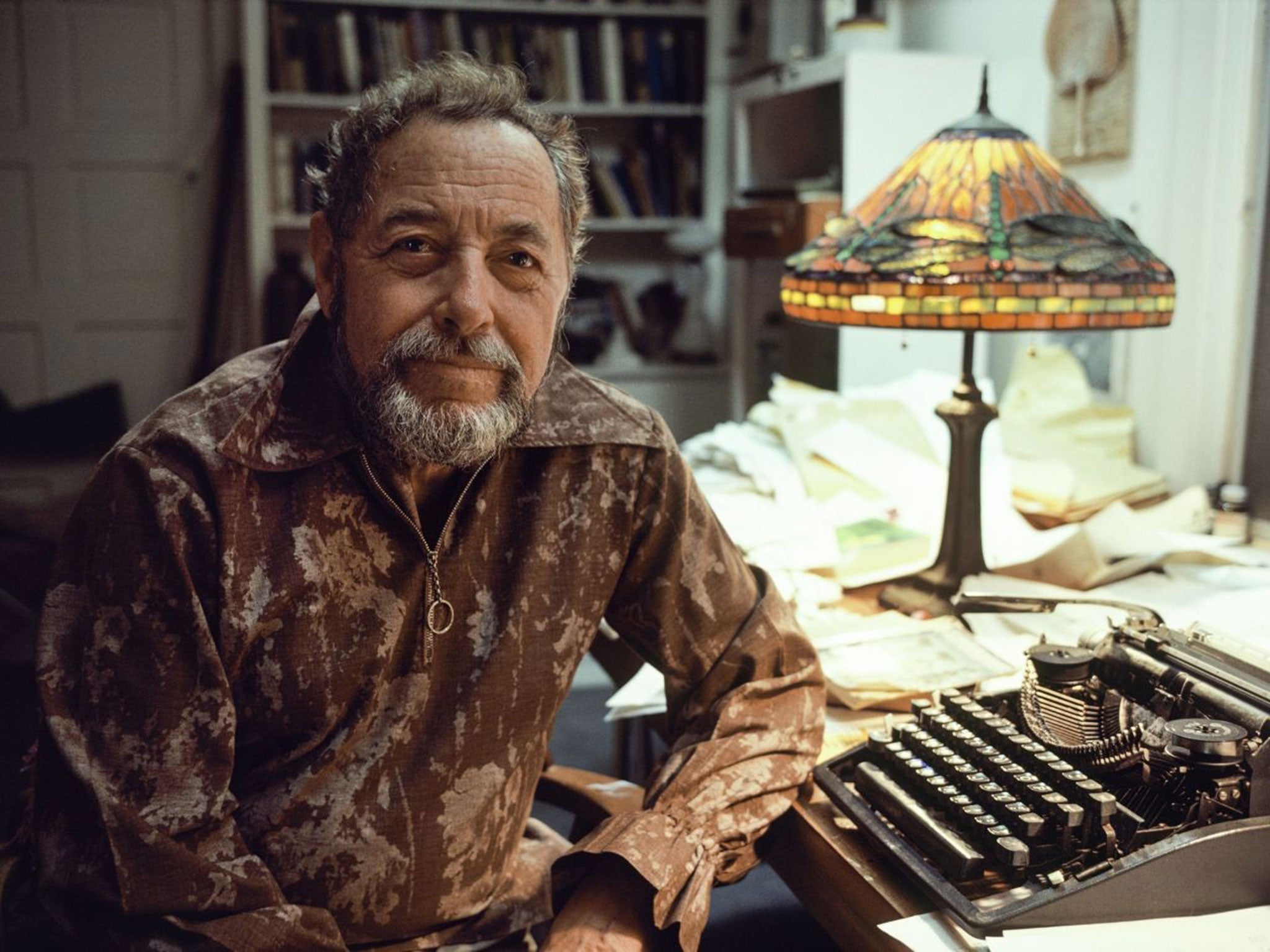

Your support makes all the difference.John Lahr, award-winning author and chief theatre critic emeritus of The New Yorker can be discerned through a side window of the door of the London club where we have planned to meet. He is lost to the world, reading a hefty book intently. I have cause to watch him in this tranquil activity for a couple of minutes because I am having no luck in attracting the attention of the nice man who eventually lets me in to this Soho establishment.

The tome that Lahr is so absorbedly reading is his own latest work, Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, and it’s no wonder that he cannot put it down. It is a masterpiece on several levels: of synthesis and analysis (an amazing life apprehended afresh, with great learning lightly borne and a strong streak of showbiz savvy; a page-turner that is almost embarrassingly devourable).

Of course, anyone familiar with the interviewing game (and Lahr has formidable form in this area) will know that an interviewer never forgoes an advantage. And the chance of ambushing him deep in the perusal of his prose is not one I chuck away lightly – and I’m afraid that “Mr Lahr, reading yourself, I see,” is my opening gambit, once I am eventually ushered into his presence.

It is to Lahr’s great credit that while, with ironically cocked brows, he acknowledges the comedy of the situation, he shows not the tiniest trace of fluster or embarrassment but goes into professional candour mode: “It’s so long since I wrote this,” he says, pointing to the hernia-inducing volume, “and I’m speaking to you today and I’ve got the Platform at the National with Nick Hytner and I’ve got all these talks I have to prepare.” Lahr has been caught out mugging up on Lahr. Nice work if you can get it. And so refreshingly direct compared to the behaviour of the Independent’s chief theatre critic, who has been known to cross to the other side of the road rather than be seen in the vicinity of one of his reviews, when blown up outside a theatre, lest he be thought vain.

Anyone meeting Lahr for the first time will experience a faint sense of déjà vu. The facial features mark him out as a kind of pasteurised version of his father, the actor and vaudeville star Bert Lahr, best known as the Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz and for originating the role of Estragon in the first Broadway production of Waiting for Godot.

Lahr was chief critic of the New Yorker for 22 years, and the only critic to appear as a character (played by Wallace Shawn – fittingly enough the actor/dramatist son of the legendary New Yorker editor, William Shawn) in a movie scripted by Alan Bennett. The film in question is Prick Up Your Ears, Bennett’s very Bennett-esque take on the ultimately fatal relationship between Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, as relayed and analysed in Lahr’s bestselling biography.

I expect this to be a touchy subject as the Lahr figure in the Stephen Frears’s 1987 movie is an exploitative nerd in a pattern of unequal marriages and comes laden with all the baggage of Alan Bennett’s very ambivalent attitude to the subject of biography and biographers. Lahr is wry and philosophical: “It sold the book and it’s a very good, tight script. My own view is that that character [the Lahr figure] could never have written Prick Up Your Ears.” He recalls with amusement how, on the set, Vanessa Redgrave – who played Orton’s redoubtable agent, Peggy Ramsay – treated him “as if she thought I, too, was the schmuck.”

It’s certainly the case that the biographer in the film would be constitutionally incapable of pulling off a feat of the magnitude of Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, his 765-page magnum opus on Williams. The book has been long in gestation. In 1994, Lahr, by now the New Yorker’s senior drama critic, was approached by a publisher for assistance in liberating a book. Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams was by Lyle Leverich, a San Francisco theatre producer whom Williams had twice authorised in writing to tell his story. In Lahr’s words, it had had “a five-year stranglehold” inflicted on it by Williams’s soi-disant literary executor, Lady Maria St Just.

The result was a New Yorker essay on the unedifying antics of the estate which opened with envenomed equipoise, saying of the woman that she was “neither a lady nor a saint nor just”. There was then a plan that Lahr would complete the work of Leverich (now deceased) with a second volume. In the event, he has approached the whole life in his distinctive manner, the book arriving with plaudits not marred by understatement: “A masterpiece about a genius” is Helen Mirren’s verdict on the front cover.

Often, reading this biography, which begins with the huge success of The Glass Menagerie in 1945, you aren’t quite sure whether to laugh or cry, such is Williams’s tendency to squander the goodness given to him and yet to wrest winning grace and humour from his humiliations. By the time of his death in a hotel room in 1983, the man who had bagged a couple of Pulitzer Prizes – for Streetcar in 1947 and for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955 – had not had a major Broadway hit since Night of the Iguana in 1961.

Lahr does not sentimentalise what Williams quipped was his “Stoned Age” in the 1960s. Nor does he underplay what Richard Eyre has called “the drollery that runs under all his work like a fast-flowing stream”. But the wretchedness of being so misjudged and underestimated in his later years hits you at times like a sharp gritty wind. How keenly madness stalked his life is brought home with devastating force when Lahr pulls out a xerox of what turns out to be the medical record at Farmington State Hospital in Missouri of Williams’s beloved schizophrenic sister, Rose, whom their mother had lobotomised (behind his back) when she began to make sexual abuse charges against their father, Cornelius.

Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh is published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments