Syrian Notebooks: Inside the Homs Uprising by Jonathan Littell (translated by Charlotte Mandell) - book review: Life, death and no easy answers on the frontline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

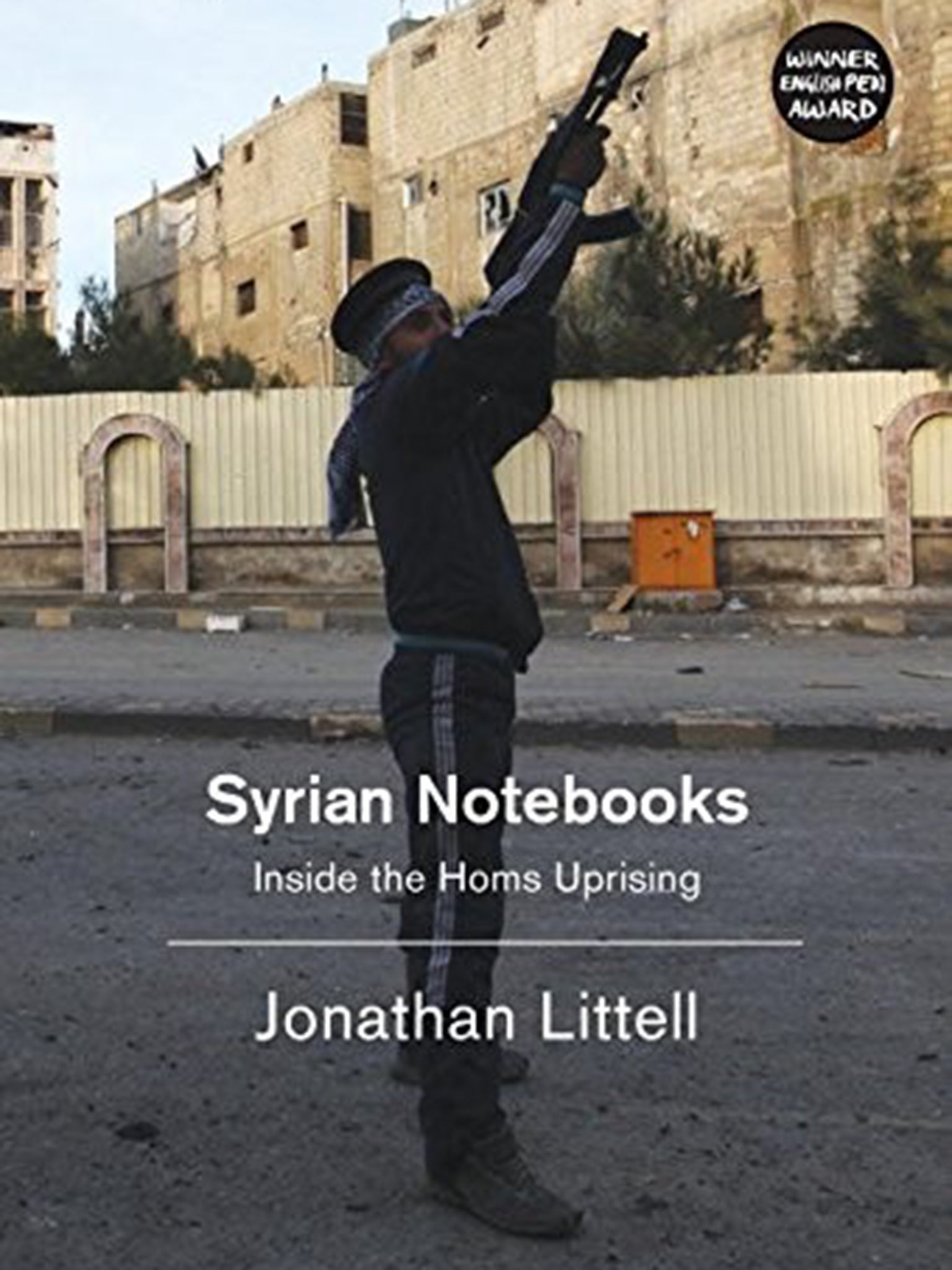

Your support makes all the difference.In mid-January 2012, the American-French author Jonathan Littell travelled to Homs in Syria with his colleague Mani, a photographer and translator.

They were smuggled into the city by opposition fighters with the Free Syrian Army and spent three fraught weeks bearing witness to the regime’s bombing of residential neighbourhoods and snipers picking off innocent civilians.

Littell was there to write a series of articles for Le Monde. On his return he realised that his extensive notes could also make a book documenting a pivotal moment in the conflict. Littell’s own emotional journey follows the sad trajectory of the opposition’s resistance.

At first he appears almost buoyant in his macho naming of the guns and weaponry used by both sides and their likely provenance. Littell adopts a nom de guerre, drinks whisky, the preferred panacea of hardened war journalists, and never complains about the discomfort of sleeping in bombed-out houses with the sound of gunfire all around. Gradually though, as the violence escalates, Littell starts to tire. He can’t shake a bad cough and becomes obsessed with meal times. He finds it increasingly hard to bear witness to the atrocities being committed day and night.

Listening to the numerous accounts of activists, fighters, doctors and ordinary citizens, Littell and Mani (aka Ra’id) have to sift through the information and decide what is fact and what may have been embellished. Some members of the FSA are suspicious of them, wary of it being reported that civilians have joined their ranks in case it supports the regime’s claims of “terrorism”. Others claim every death is regime-orchestrated.

A doctor describes in graphic terms how the wounded, both civilians and fighters, would be taken to the military hospital where he worked and were brutally tortured. He offers them evidence filmed on a camera-pen. “There were two torture tools,” he tells them, “an electric cable and strips of reinforced rubber.”

The YouTube videos the activists share with the journalists are gradually replaced by the physical bodies of the wounded and the dead. Littell conveys his sense of horror in stark, fragmented prose. After one particularly brutal day, his despondency is reflected in his writing and deteriorating health: “The coughing fits... undo me completely, leave me empty and trembling for a long moment.”

On his return, Littell warned Alain Juppe, then French foreign minister, that “the regime was doing its utmost to provoke cycles of sectarian violence while the FSA was frantically trying to contain them; born out of despair the Islamist temptation was growing but had yet to gain any serious ground.” Tragically, Islamic State is one consequence of the West’s inaction.

At the time, Littell was not to know that Homs would be bitterly fought over until last May, when rebel forces evacuated the city. But he clearly foresaw that “playing the extremists against the moderates” would serve President Bashar al-Assad’s regime well. More importantly, he realised that if nothing was done to curb the bloodletting, Islamist extremism would take hold.

Verso books £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments