State of Emergency: Britain 1970-1974, By Dominic Sandbrook

Gramsci's famous remark about the old dying, the new not yet being born and a variety of "morbid symptoms" declaring themselves in the interval is a bit too often quoted these days. All the same, it is uncannily prophetic of the period in British history covered by the rise and fall of Edward Heath's government, a time when the consequences of having won the Second World War but lost the peace that followed had become dramatically apparent to everyone but the losers.

A complacent and badly-run industrial base had failed to exploit the marketing opportunities of the 1950s, when half of Europe lay in ruins; "affluence" had revolutionised the middle-class lifestyle, while leaving large parts of the population staring enviously from beyond the patio window. "Liberation" and "equality" were in the air, to the great distress of millions who wanted neither; and the tensions realised by this collective loss of nerve seemed to have plunged nearly every national institution into a state of near-continuous trauma.

The cracks, if we are to believe Dominic Sandbrook's shrewd and well-researched book, began at the very top. The 1970-74 political establishment was one of the last to contain politicians who had grown up in the 1930s and fought in the Second World War. This grounding bred not only an understandable concern in the face of unemployment statistics, but a great deal of misplaced sentiment for a world that had already begun to dissolve.

To a generational drawback could be added straightforward lack of imagination. Robbed of its incoming Chancellor, Iain Macleod, the Conservative government front-bench consisted of an organ-grinder and his monkeys. Her Majesty's loyal opposition was in many cases even worse: Harold Wilson interested only in short-term advantage; Roy Jenkins about to give up a fairly vestigial attachment to Labourism; Tony Benn busy reinventing himself as a socialist messiah; Tony Crosland, the shadow environment secretary, regarding the conservation movement as "morally wrong when we still have so many pressing needs that can only be met if we have economic growth".

None of this explains the sheer antagonism that was the early 1970s' defining mark. Or perhaps it does, for the conflict was not so much between capital and labour (although there were plenty of strikes) or between freedom and repression (although plenty of people were repressed, not least by freedom's consequences), but between a state run on oligarchical principles, and an electorate in search of accountability. It was an era of contested planning enquiries, of building schemes and motorways pushed through in defiance of local opinion.

Nowhere is this sedulous fixing more apparent than in the manoeuvres that secured Britain's entry to the EEC in 1972. Here the loss of sovereignty that went with European law was unmentioned by negotiators. Denis Healey pointed out that if Heath had explained the implications of the European project, "he wouldn't have got it through".

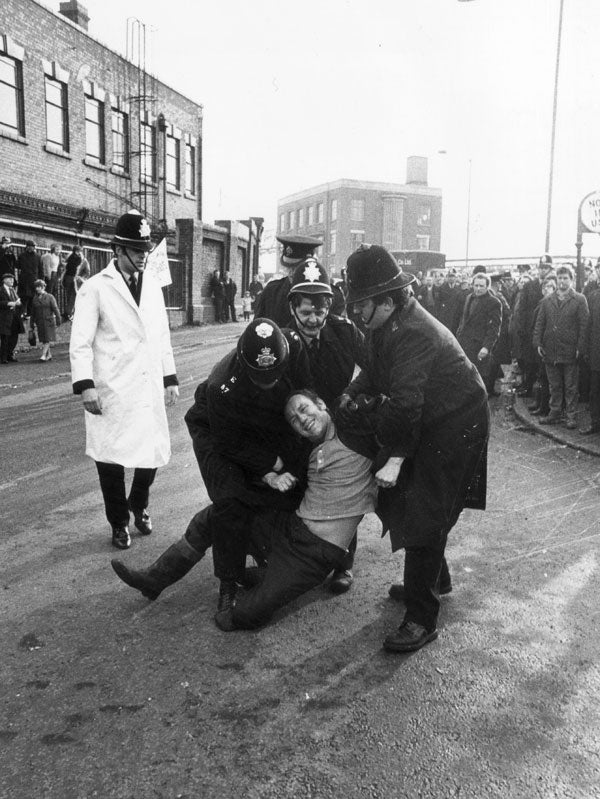

Yet Gramsci's morbid symptoms weren't merely a case of protesting town-hall galleries or the Bath Preservation Society's campaign to save Georgian squares. They also expressed themselves in industrial disputes, caused, as Sandbrook demonstrates, not by excessive union power but by the weakness of a leadership that had lost touch with its members' aspirations: "What people speak now is the language of expectation" as one TGWU official put it. The gap was most flagrantly apparent in the field of race.

Sandbrook's chapter on race relations, one of the best, notes the "raw, resentful tribalism" of much working-class comedy, and concluding that the widespread hostility to Ugandan Asians or second-generation West Indians was usually a filter for a whole range of socio-economic complaints. The Blackburn women questioned by Jeremy Seabrook were, at heart, ashamed of their racism. Their anger, he thought, was "an expression of their pain and powerlessness".

The aesthetic implications of this disquiet were apparent on every bookshop and television screen. A few technophiles of the JG Ballard school might peddle the vision of a sky-scrapered, concrete-carpeted future, but the whole cultural tendency of the early 1970s was retrogressive: "a revulsion from technology and modernity and a renewed love-affair with an idealised national past," Sandbrook decides.

National Trust membership reached record heights. Even progressive rock – fey, Hobbity, coyly pastoral – mirrored this flight from the present. The 1970s might have been the time when, as more than one social historian has suggested, the full implication of the 1960s kicked in: on this evidence, most British citizens wished that the Age of Aquarius had never occurred.

What remains, amid a series of economic crises, three-day weeks, miners' strikes and bloody conflict in Northern Ireland, is an ominous detachment of government from governed. The enormous reputation enjoyed by Enoch Powell was, as the Guardian's Peter Jenkins noted, testimony to a widespread feeling that "politicians are conspiring against the people".

Full of spirited quarrying in ancient TV programmes (Dr Who is revealed as a vehicle for eco-prophecy) and sage contemporary judgments which time, alas, has not supported (the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was "a welcome contrast to other African leaders and a staunch friend to Britain," reckoned the Daily Telegraph), State of Emergency is, above all, an exercise in determinism. Not one of its protagonists – Tory minister or Labour opponent, free-market agitator or state socialist, trades-union chief or CBI pundit – could deny, having read it, that Mrs Thatcher had to happen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks